By Dr. Samuel Kassow

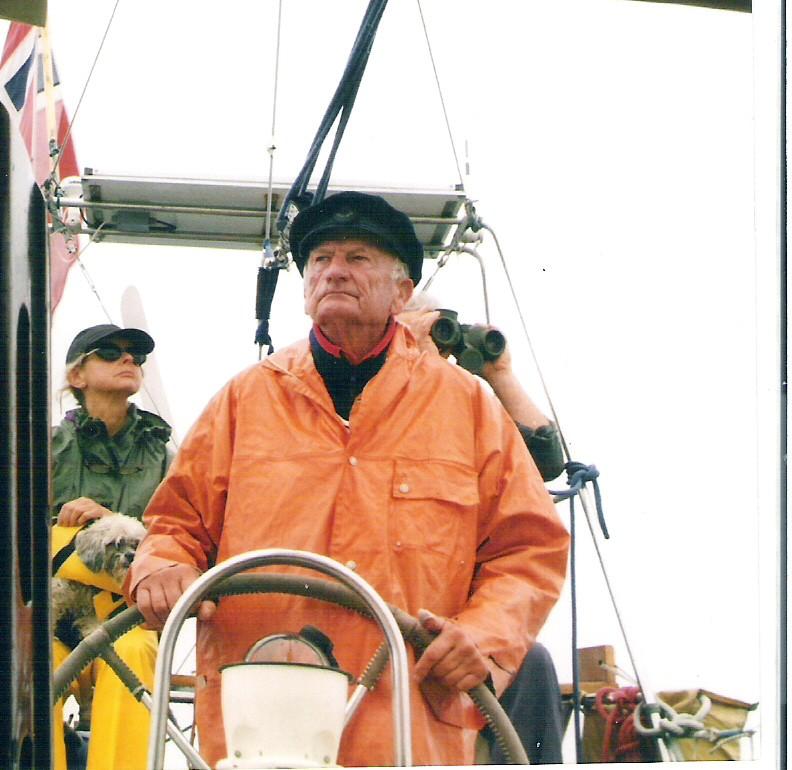

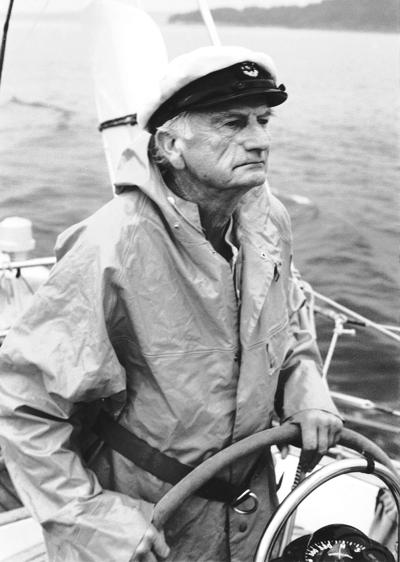

Arne Brun Lie was born in Oslo, Norway, in 1925. He had a sheltered middle-class upbringing in a suburb near Oslo, where his father worked as a master tanner. Arne’s first love was sailing, and he spent happy summers in the Sea Scouts, steadily honing his skills. He became an expert sailor and, thanks to his father, he also learned how to build boats from scratch.

Two months after Arne’s 15th birthday, on April 9, 1940, Germany invaded Norway. While the German Navy suffered heavy losses on the approaches to Oslo, Norwegian resistance collapsed within two months and the Germans completed their occupation of the country by June.

While the Germans regarded the Norwegians as racial cousins worthy of far better treatment than the Poles, their occupation of Norway became increasingly oppressive. The Germans had hoped that the king and the legitimate Norwegian government would stay in place and govern the country, as had happened in Denmark. But when King Haakon VII and the government fled to Britain, the Germans recognized Vidkun Quisling, the unpopular head of the Norwegian fascist party Nasjonal Samling as prime minister. Ultimately, though, the real power rested in the hands of Germans, specifically the rabid Nazi Josef Terboven, whom Hitler appointed Reichskommissar for Norway, and SS Gruppenführer Wilhelm Rediess.

While a majority of the Norwegian population opposed the occupation, there was plenty of collaboration as well—enough to endanger Norway’s small Jewish population and those Norwegians who chose to resist the Nazis. It was the Norwegian police, rather than the Germans, that played a key role in the roundup of Jews in November 1942. And 15,000 Norwegians volunteered for the Waffen-SS and the Wehrmacht.

Indeed, it was the STAPO, the Norwegian political police, that arrested and tortured Arne before turning him over to the Germans. In 1943, when Arne was 18, he was asked to join a Norwegian resistance cell, an “action group” that was to prepare various acts of sabotage. He eagerly agreed, shrugging off a warning that he would face torture and execution if caught.

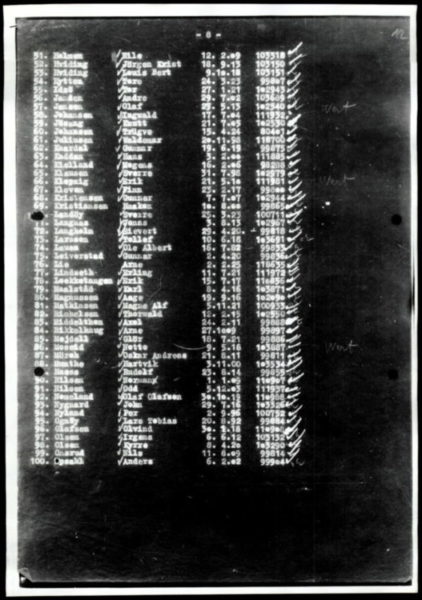

In the spring of 1944, Arne’s group went on a mission to destroy lists of Norwegians targeted for forced labor. The mission was compromised, and the STAPO trapped most of the group. Although Arne himself had not joined the mission—his training had not yet been completed—the police somehow got his name. They stormed his house in the middle of the night, arrested him, and took him to STAPO headquarters, where he was badly beaten.

Soon afterwards, the STAPO moved Arne to Akershus Castle, a notorious prison, where he was handed over to the German Gestapo and suffered more torture. In Akershus Arne found out that three close friends of his who had gone on the mission—Jon Hatland, Per Stanger-Thorsen, and Lars Eriksen—had been caught and were in the same prison. The four of them were tried before an SS court. Jon, Per, and Lars were sent to be shot. By some miracle, Arne was not executed. He was told later that one reason for his reprieve was that the Germans had misplaced his file.

Although spared execution, Arne was sent to a series of brutal Nazi concentration camps, where most of his Norwegian co-prisoners died. His case fell under the notorious Nacht und Nebel (Night and Fog) Decree, issued by Hitler on December 7, 1941. The purpose of this decree was to crush resistance to German occupation by denying arrested prisoners any contact with their family or anyone else; they would simply vanish “into night and fog.” The directive streamlined German repression by eliminating the necessity of trying each suspect in Wehrmacht military courts. Nacht und Nebel prisoners had a special status, wore a large “NN” on their uniforms, and were, in effect, sentenced to death.

In June 1944, Arne and some other Norwegian NN prisoners were taken to Stettin on a German ship and from there by rail to Natzweiler, a notorious German concentration camp in Alsace. Over time, nine convoys of Norwegian NN prisoners, totaling 504 men, arrived in Natzweiler. The mortality rate in the camp—because of inadequate food, hard labor in a stone quarry, and rapid marches up and down the mountain where the camp was located—was very high. Up to 20,000 prisoners died there in all. Natzweiler was also notorious because of the medical experiments performed there; eminent German professors used the prisoners to test vaccines against typhus and investigate the effects of mustard gas and typhus.

As the Allies approached Natzweiler at the end of August 1944, Arne and the other surviving prisoners were transferred to Dachau and then to Dautmergen. Although Arne described the guards at Dautmergen as “Polish SS,” it is more probable that they were Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans who lived outside the Reich), perhaps from Silesia or Pomerania, former Poles who had opted for German nationality. There were no Polish SS formations per se.

In his original interview, Arne gave graphic descriptions of the horrors he witnessed: hangings, beatings, senseless sadism, fellow prisoners strangling a comrade because he had stolen a tin of meat. One by one, the Norwegians died; very few lived to see the end of the war. During his time in the camps, Arne suffered acute dysentery and typhus. By the time the war ended, he was 19 and weighed 90 pounds.

In April 1945, facing a looming German defeat, Heinrich Himmler, the leader of the SS, sought to burnish his image by making a deal with the Swedish Red Cross to release all Scandinavian prisoners. On May 1, 1945, Arne arrived in Copenhagen, alive and safe.

After the war, Arne went to England to study tannery. He returned to Norway, married, and had three children. In the 1980s, now divorced, he immigrated to the United States and had two children with his second wife. His first love remained sailing. He crossed the Atlantic under sail four times.

For many years, Arne did not want to talk about his experiences, but, in time, he decided to speak out. The 1961 Eichmann trial, growing ignorance about Nazi atrocities, and many serious conversations with friends persuaded him that telling others about what he had seen and lived through was a responsibility he could not shirk.

———

Additional readings and information

Brun Lie, Arne (with Robby Robinson). Night and Fog: A Survivor’s Story. New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1990.

Passage, a 1991 documentary about Arne’s cross-Atlantic voyage in a sailboat he himself built and his visit to the concentration camps where he was imprisoned during the war: http://www.newfilmco.com/paspage.htm.

Arne’s unedited testimony at the Fortunoff Video Archive (available at access sites worldwide): https://fortunoff.aviaryplatform.com/collections/5/collection_resources/1185.

###

Arne Brun Lie: My name is Arne Brun Lie. I am Norwegian citizen born in Oslo, 2nd of February, 1925. I was 15 years old when the Nazis came and raped us.

When I was 18, I was asked if I would like to join the resistance movement. We were told that, if we get caught, we would be tortured and probably executed. And in our young enthusiasm, we said, “Yes, that’s fine. We will do that.”

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Those Who Were There: Voices from the Holocaust,” a podcast that draws on recorded interviews from Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. I’m Eleanor Reissa.

Arne Brun Lie didn’t talk about his experiences in World War II for 40 years. But that didn’t protect him from the nightmares. At the urging of his second wife, Ellen Korey-Lie, Arne decided to share his story. That’s how he finds himself in a TV studio in Peabody, Massachusetts, on November 6, 1987, with interviewers Janet Miller and Ann Walker.

Arne is seated against a wooden lattice fence and a big, leafy plant. He’s dressed in a tweed sport coat, blue and white striped shirt, and a dark tie. He has blue eyes, gray hair, and a narrow face weathered from years of sailing.

Arne joined the Norwegian resistance in 1943. He went through what he called “very, very basic training.” He learned how to place magnetic mines on the hulls of ships and how to use a knife in hand-to-hand combat. But Arne only got to participate in a handful of actions against the Nazis before he was arrested.

———

ABL: My friends were brought to Gestapo headquarter and tortured and beaten up. A few hours later, I was arrested at home by six men, fully armed.

Interviewer: Your home at that time, were you with your parents?

ABL: Yeah.

Interviewer: Were they there when—

ABL: They were there. My younger sister was there. My mother was there. My father was there. And they were held at gunpoint.

Interviewer: Describe to us your feelings at that time.

ABL: I, I was, of course, very scared. But I thought, Oh, this is something I’ll get away with. I played innocent. And then they took me down to the Norwegian Nazi police headquarter. And there everything really changed.

There were three or four beating me at the same time and yelling and screaming. And then they put me on a stool. And two guys were hitting me with ropes, over the back and head and everything. And I passed out several times. But I was hollering and I spat at them and I, you know, I, I was so mad. But of course they, they kept on and on and on and on. And then, they, they asked me if I knew my three friends. I understood that I was fighting a lost game, that they knew all about me.

I was then transferred from Norwegian Nazi police to the German Gestapo. And they thought that I really knew more than I did. And they really beat me up. And, you know, for these days of questionings, they were very tough.

And then, more or less I understood that the questioning, uh, was over. I was suffering. You know, I was black and blue all over and urinated blood and I really looked miserable.

There is, in Oslo, there is a medieval castle where they, they kept prisoners. And we were sent down there. Uh, of course we understood that the situation was very, very, very dangerous.

Then, one day in the prison, this was in May 1944, I was taken out and interviewed in an office by a German fellow with black tie and he asked if I had some last messages to send to my parents and things.

And they were joking about us. We hadn’t been able to shave. And we really looked miserable. And one of my friends, they looked at him and they laughed. And they said, “But you look like Jesus. Well, you will soon see him,” they said. You know, it was so, so awful. And, of course, we were scared. But we were also mad.

And then, the day after, I was taken to Gestapo headquarter. When I came up there, there was a lot of hollering when they saw me, and they said, in, in German, “Aber er lebt doch!” “He is alive! How come?” And then they looked in the files everywhere, and they couldn’t find my file, which is something extraordinary in the German bureaucracy.

And then I heard them running around… “Er hat Glück gehabt.” “He’s been lucky, he’s been lucky, he’s been lucky.” And then they changed tone and almost became friendly. And I was then a problem for them. They called my parents. They said, “Send him some clothes.” And I waited there. And my oldest sister came down with something, pair of boots, I don’t know. And we were able to talk together for two or three minutes. That was, for me, the turning point. She gave me such courage. She whispered… She hugged me and whispered that, uh, we’re winning the war.

Then I was transferred to a concentration camp just outside Oslo. And there it was a different atmosphere. They were all political prisoners and the underground movement worked there as well. They had secret radio receivers. There were news bulletins under the noses of the Gestapo. And everybody, because they knew that I had been under tremendous stress, they were so nice to me. And I was the junior. I was the youngest almost of all of them.

And then, one day in June, a group of us were gathered together. And we were told that we were going to be sent to, to Germany.

Interviewer: Describe to us your experiences in Germany when you first arrived.

ABL: We were shipped on a German ship. We saw the lights of neutral Sweden. And then we traveled through Germany and we saw the fantastic destruction that had been done by bombardments. I remember we, we went through Mannheim through the town for 45 minutes, we didn’t see one building which was not in ruins.

Anyway, we crossed the Rhine. And we were taken up to a place called Schirmeck in Alsace. And we were marched up a mountainside. And we came to a camp on a slope of the mountain called Natzweiler.

We were taken to be deliced in the shower there. We were shaved. Everything was taken away from us, of course. Then an SS officer came and made a speech to us. And he said the following, that “You are now prisoners here, and you are very dangerous people. And you are in a category of prisoners which is called”—the German word was—“‘Nacht und Nebel,’” which translated means “night and fog.”

He was hollering and screaming and telling us that we had helped the enemy in the night and the fog. And that, also in the night and the fog, we should die. And he said, “None of you are going to get out of here alive.”

My stay there was relatively short. We didn’t work there. But we had very, very little food. And we spent times being lined up on the, what they called, Appellplatz. We were counted, recounted, counted, recounted. From five o’clock in the morning, we were there. We had to witness official beatings. A man, if a man had stolen a piece of bread, he had 25 strokes. We had to witness hangings of prisoners who had tried to escape.

I remember one, um, execution. The gallow was at the top of the slope. And there were several terraces down. And we were standing down. And we had to take our prison caps off when they hung a fellow. But this time, um, the knot must have had some grease or something, but, because it slipped and the poor fellow reached the ground with his toes. And then one SS, with his polished boots, dug a little hole in the gravel, till he hung.

This was not the worst in Natzweiler. One day, there was a great deal of commotion at the gate, up on the top of the hill. Five girls were being escorted around the outside of the camp. And, uh, they were English and… One, one or two French and two or three English girls. They were radio operators. And they had been dropped behind the lines. And they were caught prisoners—in uniform. And they waved to us and made “V” signals, you know, winning, winning the war and all that. And these girls were taken down to the barracks at the bottom of the camp, where they had the crematorium and the baths. And they were hung there.

The war was approaching. We thought it would be over every three, three weeks, because the invasion was there in Normandy. But it didn’t happen like that. It was decided that we should be evacuated from Natzweiler. We were all massed together in rows of five, and we started a march, heavily guarded by SS and dogs. And we went down the mountain slope like a worm of prisoners, you know, going five abreast and tight together, and with the dogs and the whips and the arms and the shouting of the Germans, you know, the “Los, los, los, los.” And it was dark. And then we saw behind us this, this crematorium, and with a pipe stack, which was metal, red hot. And they had hung 400 people that night in there. That’s the last I saw of Natzweiler.

Then we were, we were marched down to waiting trains. And a group of us—I think we were about 60 Norwegians—we were transported to a camp called Dormettingen, which is near Stuttgart, in Germany. And that was the absolute bottom of everything that we experienced. There were no facilities at all. We slept in tents. We slept on the ground. It’s now coming September, October, and we were working.

They were having surface mining for shale—I think it’s called shale. And they were going to make oil out of shale. And we were working there, and the conditions were absolutely appalling. After two months, 16 of us were alive.

We were beaten… It was Polish SS, and that’s the worst we have seen. They, they were screaming and beating. And they shot at us for fun. While we were marching, they would take a cap and throw it in a field and tell a prisoner to go and get it and then, and then shoot him.

Most of us had severe cases of dysentery. And this is unpleasant, but we, we had no water, no nothing, no shifts, and our pants became absolutely incredible. I had shit in my pants that was almost two months old. And I reached the lowest of my physical condition. I weighed 90 pounds. I was 19 years old, and I looked like 65. Anyway, I saw that I had to do something because I could count the days, I was so weak.

And then there was a sick transport, it was announced. Sick transport. And I said to myself, This is my chance. And I managed to get on the list, me and a Norwegian sailor, Juliuson.

And then one day, a few buses came and we were loaded in the buses with heavily guarded, you know… And then the buses took a very different direction from the railway station. And Juliuson and I said, “Okay, they, they’ve got us.” Because what they often did then was they took the sick people and just killed them. I must say that—whew… I said, “Pity it’s going to end like this.” Then the buses turned towards the railway station. And we said, “Okay, maybe we’ve made it now.”

But that wasn’t the end of, of it. We were loaded in cattle wagons, and we were 80 people in one cattle wagon. Juliuson was stronger than me, and we were successful in getting a corner. And we defended our place there, because nobody could sit. We were all cramped. But we were so weak and people started to die. And they were stacked in the corner, and we got a little more room.

We were 20 alive when we arrived in Dachau. And the transport must have taken a long time, because the bodies were starting to decompose.

When I arrived in Dachau, the news spread that a terrible transport had arrived. And I was found amongst these other bodies—I couldn’t walk, I couldn’t do anything.

Our half of the camp had lice, and we got typhus. I got typhus. In one and a half months, about 16,000 people died around us. And nobody would come there. Nobody would do anything. They just put some food in.

I remember I was half unconscious, and I was going to the bathroom or Waschraum, whatever they call it. And it was very, very cold, and they had taken out dead bodies and stacked them in the bathroom. And for air raids, something, there was a blue lamp casting a grotesque picture of the bathroom, the running water, the dead bodies piled up there. And there was a man who, who was mad, and he was just screaming and screaming and screaming and screaming. And I, I have this picture of the scene in the bathroom. I don’t know, I was helped back to bed somehow.

And suddenly, one day, a number of buses with Red Cross on and Swedish flags from neutral Sweden, they came in and they, they had two nurses. And I thought, This is not— I don’t believe it. I don’t believe it. And I was still very weak after the typhus. And then we were told that we were going to be sent to another concentration camp in northern Germany, and that we were from now on under the protection of the Swedish Red Cross. That was end of March 1945.

Interviewer: I’m sure you’ve thought about, with everything you’ve been through, near death so many times, why do you think you survived?

ABL: I think there are several factors. And, of course, number one is luck. But I think another factor really contributes in my case. It’s, uh, some sort of an—maybe stupid but—eternal optimism. They’re not going to get me. And I think you’re born with that. It’s like an electrical motor that you have that, when things go really wrong, it starts. It starts. I don’t know why and how. I don’t know.

For almost 40 years, I haven’t told the story to… To my sisters, yes, and to a few friends, but it was almost like, uh, that was that, and don’t let’s talk about it. That was le passé. Why bring such a terrible thing up? Until, when you get to a certain period in your life, and it hit me. I had nightmares on nightmares. And then I thought, I have to tell it.

And also, when I have seen and heard that people tried to say that this didn’t happen. I see it as my duty to, to tell people that it happened to the Jewish people, and it happened to the non-Jewish people also. And what can we do to prevent these things from happening again.

There is a horrible misunderstanding. Vicious people can say this didn’t happen. But I’m here, and it did happen.

Interviewers: Thank you so much for sharing your story with us. Thank you.

ABL: I wouldn’t say it was a pleasure, but, uh, I’m glad I did it. Is it over now?

———

ER: This interview was just the beginning for Arne Brun Lie. In the years that followed, he often shared his story at schools and community groups in his adopted state of Massachusetts.

Arne Brun Lee died on April 11, 2010, at the age of 85. He was survived by five children and eight grandchildren.

One of Arne’s daughters, Siv Lie, credits her father’s survival in part to his spirit. She says, “The Arne that we knew was one of the most giving, thoughtful people, who lived life and didn’t sweat the small stuff.” Siv’s sister, Cecelia Lie, adds, “We’re grateful for how joyful and playful and silly he was. We could go on forever about how much we loved him.”

To learn more about Arne Brun Lie’s life story, please visit thosewhowerethere.org. That’s where you’ll find additional background information, photographs, and links to his 1990 memoir Night and Fog: A Survivor’s Story. You’ll also find a link to Passage, a 1991 film that documents Arne’s cross-Atlantic voyage in a sailboat he built himself—and his return visit to the concentration camps where he was imprisoned during the war.

To hear more from “Those Who Were There,” please subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. You can also go to thosewhowerethere.org.

“Those Who Were There” is a production of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, which is housed at Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Department.

This podcast is produced by Nahanni Rous, Eric Marcus, and the archive’s director, Stephen Naron. Thank you to audio engineer Jeff Towne and to Christy Tomecek, Joshua Greene, and Inge De Taeye for their assistance. Thanks, as well, to Sam Kassow for historical oversight and to our social media team, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Ljova Zhurbin composed our theme music.

Special thanks to the Fortunoff family and other donors to the archive for their financial support. I’m Eleanor Reissa. Thank you for listening.

###