When Nazi troops seized the Polish farm where Celia Kassow was in hiding, she fled once again—this time into the forest, where she joined the Soviet partisans.

Photos and Artifacts

By Dr. Samuel Kassow

For more on Celia Kassow’s story, be sure to listen to Celia Kassow — Part 1 as well as our episode featuring her son, Sam Kassow, who tells a breathtaking story about the Polish farmer who saved his mother’s life.

This two-part episode, which features the testimony of Celia Kassow, née Cymer, tells the story of a teenaged girl who grew up in a small town in a remote, underdeveloped area of prewar Poland. The word Holocaust often conjures up images of an impersonal bureaucratic juggernaut, of long trains carrying millions of faceless, anonymous victims to death factories. But, as Celia’s testimony shows, there was another Holocaust, where in countless small towns and villages, death was up close and personal—where neighbors betrayed and even murdered old friends for a few trinkets, and where the guards who hurried Jews along to nearby shooting pits were often former classmates or longtime customers. And then there were other neighbors and friends who, at the risk of their own lives, were ready to extend a helping hand.

Celia’s testimony also reminds us not to expect survivors always to give a totally accurate, chronologically coherent, and historically “objective” story. Historians who want rock solid evidence of “what actually happened” should use testimonies like this one with caution, not because Celia set out to lie but because she, like so many others, needed to tell a story that would help her come to terms with the past.

Many decades separated Celia’s wartime terror and her 1980 recounting of it in a comfortable studio in New Haven, Connecticut. For some survivors, these interviews afforded a second chance to tie up loose ends, confront traumatic memories, and revisit decisions that left deep scars of guilt and shame. They offered the opportunity to refashion a narrative that would tell, if not the exact story, then an account of a journey that began in hell and ended with some semblance of stability and normalcy. Celia’s testimony may well be such an example—a story where the victim created a kind of convenient bridge that would link the past and present in a way that was less threatening or painful.

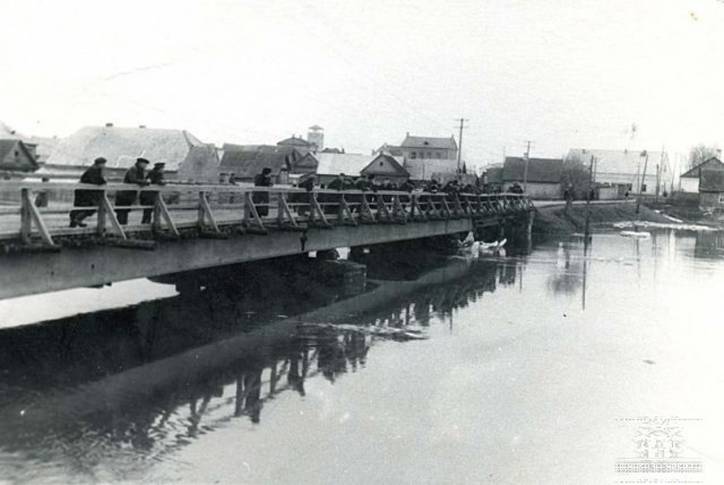

Celia was born in Szarkowszczyzna, Poland, in 1923. The Jews, who made up 80 percent of the town’s 1,000 inhabitants, called it Sharkoystsene, while the Belarusians, who comprised most of the peasant population surrounding the town, called it Sharkaushchina. The town, which today is part of Belarus, is about 70 miles northeast of Vilnius (Wilno in Polish) in a region that the Poles called the Kresy (borderlands). For the Jews, this was Lite (Jewish Lithuania)—an area with hundreds of miles of forests, rivers, and lakes, with Polish manor houses and Jewish shtetls, and in between and all around, hundreds of tiny villages populated by Lithuanian and Belarusian peasants. The Jews of this region formed a special tribe, the Litvaks, who had a Yiddish dialect, cuisine, and religious culture that set them apart from the Jews of Poland and Galicia.

Celia grew up in a warm loving family of seven children, five girls and two boys. Her father, Shmuel, earned the nickname “Sam the American” because as a single young man, he had lived for a time in the United States, but he’d returned before World War I. Unlike the Italians or the Irish, relatively few East European Jews returned home, but Shmuel preferred to marry and raise a family in a place where life was less materialistic and more traditional. Once back home, he married a young woman from nearby Postov, Liba Cepelowicz. Between the wars, Shmuel established a relatively prosperous flax business with a partner, Hersh Berkon, who would head the Judenrat during the occupation.

The family’s life was centered in a big house on the market square, where Liba ran a popular restaurant that, on Saturday nights, also showed films. Liba was the emotional center of the family, since Shmuel was away on business much of the time. She was a tall, forceful woman, who was also active in some of the local societies that helped the poor and the sick. Two of the older daughters, Merke and Dina, married.

Dina’s son, Raful, was born in 1937. Her husband was drafted into the Polish Army in 1939 and never returned. Merke’s daughter, Lea, was born in July 1941, at a time when the Red Army had retreated, the Germans had not yet arrived, and the peasants were coming from far and wide to start a pogrom, beat Jews, and steal their property.

When Poland collapsed in 1939, it was the Soviets rather than the Germans who occupied Sharkoystsene and the surrounding region. While almost all Jews naturally preferred the Red Army to the Nazis, many still suffered a great deal under the Soviet occupation. Since Shmuel was classified as a member of the bourgeoisie, he lost his business and the Cymer family had to share their large home with unwanted guests, including local Communists. The Soviets deported many members of the middle class. The 300,000 Jews who were deported to the Soviet interior between 1939 and 1941 bitterly regretted what seemed to be a terrible fate. Little did they know that more than half would survive the war, while those Jews who were untouched by the Soviets almost invariably fell victim to the Germans. By rights, Shmuel and his family should have been deported but someone pulled strings and they remained in Sharkoystsene. Shmuel and the boys found jobs, while Celia wangled her way into an elite boarding school in nearby Druya.

When the Germans attacked the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Celia, now 17, was in Druya. In the midst of terrible chaos and confusion, she desperately tried to get home, walking on roads jammed with refugees and fleeing Red Army units. A Polish schoolmate whom she had counted as a friend slammed a door in her face and called her a “dirty Jew.” When she finally got home, a bloody pogrom was raging. By early July, the Germans had arrived and quickly began a reign of terror. Jews were subject to random shootings and beatings. They were constantly required to do forced labor at a moment’s notice. In a few months, the Germans established two adjoining ghettos, one for “productive” and another for “unproductive” elements. Celia’s family was in the former. Since hundreds of Jews were dumped into the ghetto from surrounding villages, the ghetto soon contained 1,500 Jews and overcrowding reached unbearable levels. The Germans surrounded the ghetto with tall wooden fences topped by barbed wire. Since the official bread ration was 100 grams a day, there was a desperate shortage of food, even though the Judenrat did all it could to help the starving Jews. Celia became a waitress for the local German officials, who actually treated her well. Now and then, they even gave her food to take home, but Liba adamantly refused to allow non-kosher food into the house.

The new police chief in the town was Marian Danielecki, a Pole who had probably rebranded himself as an ethnic German. Danielecki had a longstanding grudge against the Cymers from before the war and now he saw his chance to take revenge on the family. One day he propositioned Celia, who slapped him. Danielecki then ordered the police to beat her with rubber hoses all night. The next day, she was dragged, more dead than alive, to the Jewish cemetery, ostensibly to be shot. The route passed by the ghetto, and desperate Jews tossed money and valuables to the police in an effort to ransom Celia. (Her own family saw everything.) Danielecki told his friends that if Celia begged for mercy and agreed to be his lover, he wouldn’t shoot her. When she didn’t, he aimed the pistol right at her head but at the last minute he shot in the air. (This would cause permanent damage to her hearing.)

Celia returned to her job serving the Germans. The Judenrat asked her to observe everything she saw in the building and to report back anything suspicious. In mid-June 1942 the Judenrat learned that the Germans had massacred a number of nearby ghettos. On June 18, with tensions at the breaking point, Celia suddenly saw trucks full of Lithuanian police and Germans in a new kind of uniform. (These Germans were part of Einsatzkommando 9B, attached to Einsatzgruppe B. It was commanded by Untersturmführer Heinz Tangermann, who received a very light sentence in the mid-1950s.) The Judenrat had an emergency meeting and urged everyone to flee. Some Jews, including Celia’s father Shmuel, decided that they would not run but die on the spot. Many of them also began to set fire to all the buildings in the ghetto in order to deny Germans Jewish property and to create a distraction to help other people escape. Celia later learned that a local Belarusian policeman shot Shmuel. He then chopped off his finger to get his ring.

A terrible scene of mass murder and total chaos ensued. The Jews rushed to the ghetto fence and started to run, but they ran right into cordons of heavily armed Germans, Lithuanians, and local Belarusian auxiliaries, who opened heavy fire on the desperate men, women, and children. Panic set in and families lost each other in the confusion. Masses of people fell wounded or dead while others had to run over them to try to reach safety. Celia grabbed her youngest sister Slava and ran right into a local policeman with a gun. The policeman, who had once been her classmate, raised his rifle to shoot her but the gun jammed. Celia held Slava tight and kept running.

By daybreak hundreds of Jews were dead, while many others were wandering helplessly through the nearby swamps and forests. Spurred on by German promises of vodka, salt, and Jewish property, the local peasants hunted down the fleeing Jews like wild animals. Celia and Slava saw their 15-year-old sister Chaya murdered, with her eyes gouged out. A short time later they watched a mother drown her crying baby.

Students of the Holocaust might remember Hannah Arendt’s controversial book Eichmann in Jerusalem, in which she criticized the Jewish councils and asserted that had they simply told Jews to run and scatter, instead of allegedly cooperating with the Germans, many more Jews might have survived. In Sharkoystsene the Judenrat did exactly that, but in the end it made little difference.

After a few days in the forests and swamps, their numbers quickly dwindling, the surviving Jews heard that the Germans were offering an “amnesty”: all Jews would have a few days to voluntarily enter the nearby Glubok (Glebokie) ghetto, no questions asked. Although the survivors knew full well that they were putting their heads back into the noose, almost all of them, including Celia and Slava, went to Glubok. The only exceptions were a very few young men, including Celia’s two older brothers, Zalman and Hershke, who would later play a major role in Celia’s story.

When Celia and Slava arrived in the Glubok ghetto in late June 1942, they were surprised to see that their mother, Liba, and their two older sisters, along with their children, were also there. Just a short time later, Piotr Bilevich, a young man from a Polish family that had had business dealings with the Cymers before the war, showed up in the ghetto with a horse and cart. He had come to take Celia away and hide her on his farm. (In her testimony, Celia called Piotr a “peasant,” which was not entirely accurate. Peasant families usually did not send their sons to high school, as the Bileviches did.) Celia did not want to leave her mother and sisters, but Liba literally pushed Celia into Piotr’s arms and told her to go. The leave-taking was harsh and traumatic. Celia would never see her mother again.

From the very first day on Piotr’s farm, Celia realized that her new life would require very strong nerves. She divided her time between the farmhouse and a deep hole that Piotr had dug in a barn to hide her in emergencies. By this time, Celia’s two older brothers had joined the first Soviet partisan detachments in the region and visited Piotr’s farm from time to time. On one occasion, they gave Celia a pistol.

Meanwhile, the brothers had also succeeded in moving Liba and the surviving members of the family from Glubok to Postov, where Liba’s family lived. But on November 23 (according to German documents) or December 25 (according to the Glebokie Memorial Book), the Germans suddenly liquidated the Postov ghetto. The execution pit abutted a large lake and there was no place to run. Celia’s mother, her older sisters, and their children were murdered. Her younger sister Slava lay on top of Liba, who, before she died, told her daughter to play dead and then somehow get to Piotr’s farm. Although grazed in the head and the leg by two bullets, Slava played dead, then swam across the half frozen lake, and in an incredible effort of will and endurance crawled the 15 miles to Piotr’s farm. She arrived in terrible condition—severely frostbitten, her wounds infected, more dead than alive. Slava had just turned 12.

Shortly after Celia and Slava were reunited, they went through a new ordeal. German anti-partisan units swooped down unexpectedly on the farm and established a command post in the barn, right above the hole where the two girls were hiding. They spent five days in complete terror, lying in excrement and mud as rats crawled all over them. Assuming that the Germans would eventually find them, they decided to kill themselves first, arguing over who would kill whom. But just when their nerves were about to give out, the Germans left. A short while later, they endured another evening of fear when Germans arrived at the farm with an interpreter whom Celia had known before the war. Luckily, the interpreter did not give them away.

By the second half of 1943, it was becoming too dangerous to stay on the farm, and Celia and Slava, with their brothers’ help, joined the Soviet partisans. Although Celia failed to mention it in the interview, she spent much of her time in the partisans together with Piotr (a Soviet document from Yad Vashem lists Celia and Piotr in the Rokossovski detachment). They attacked German garrisons, blew up trains, and survived German search-and-destroy operations.

When the liberation came in July 1944, the Red Army drafted Piotr, while Celia, like many other survivors, fell into a deep depression that the struggle for survival had temporarily staved off. Did she want to wait for Piotr and spend the rest of her life in a non-Jewish environment? One will never know exactly what went through her mind, but in the end, she did not. After a vain struggle to resume her education, she got together with Kopl Kossovski, a Jewish man she barely knew, and joined other Jewish survivors who repatriated from now Soviet Belarus to postwar Poland. Piotr returned from the war deeply angry and hurt. He even went to Lodz to hunt Celia down. But the two would never meet again.

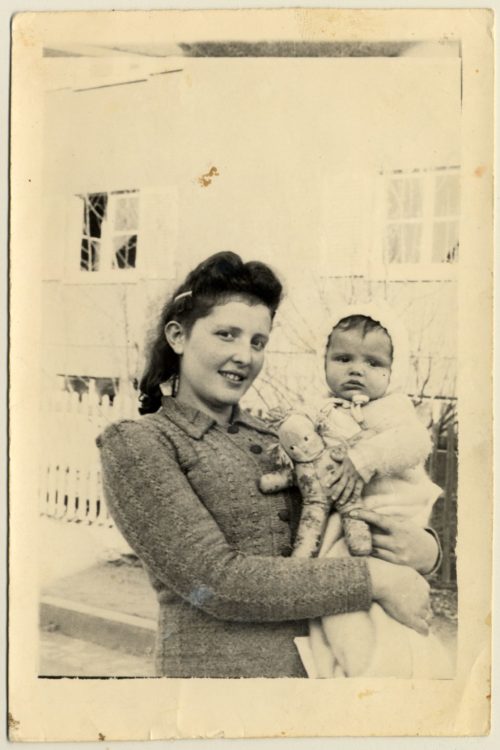

Nine months almost to the day after Celia met Kopl, their son Samuel was born in Stuttgart, Germany. Celia was ambivalent, to say the least, about motherhood; when she was four months pregnant, she tried to commit suicide by lying down on trolley tracks in Lodz. Soon after giving birth, Celia became terribly sick with mastitis and the doctors gave her little chance of survival. Their newborn son spent much of his first year in orphanages and in the care of Celia’s brother Zalman’s young wife, Sonia. It took Celia a very long time to reestablish a bond with the baby.

In 1949, after almost three years in the DP camp of Wasseralfingen, Celia and Kopl emigrated to New Haven, Connecticut, where Kopl became a tailor and Celia worked odd jobs, including waitressing and teaching driving. Their daughters, Linda and Cheryl, were born in 1950 and 1955, respectively. Celia’s marriage to Kopl, who had survived the Holocaust in Russia, was typical of many survivor marriages, where, to repeat a mordant and sardonic saying popular among survivors, the “marriage broker was Hitler” (in Yiddish, “Hitler iz geven mayn shadkhn”). People from different social classes, with totally different interests and personalities, sought to escape the loneliness and depression by finding a partner and starting a family. Kopl was a wonderful man, a caring and loving father, a hard-working breadwinner. But he and Celia did not have a good marriage. On the other hand, they never divorced and tried to give their three children as good a home as they could.

Kopl died in 1987. Celia Kassow died of cancer in February 1994.

———

Additional readings and information

Celia’s unedited testimony can be found at the Fortunoff Video Archive (available at access sites worldwide): https://fortunoff.aviaryplatform.com/r/1n7xk84j87.

###