By Dr. Samuel Kassow

In this episode, Leonard Linton, a soldier with the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne Division, recounts one of his most significant experiences in World War II: the liberation of the Woebbelin concentration camp near the German city of Ludwigslust on May 2, 1945, just a few days before the end of the war. Leonard’s testimony underscores the degree to which American soldiers—and, soon after, journalists and the wider American public—were shocked by their first face-to-face encounters with Nazi concentration camps. That they should have experienced such stunned horror in 1945, when news of Nazi camps had already been circulating for some time, reflects the gulf that existed in people’s minds between hearing the news about Nazi atrocities and actually believing that news to be true. And the camps that the American Army liberated were far from the worst; it was the Red Army, after all, that liberated the major death camps in Poland.

By any measure, Leonard was hardly a typical GI. His Russian parents had fled their homeland for the Far East after the Bolshevik Revolution, and Leonard was born in Yokohama, Japan, on January 1, 1922. He grew up speaking four languages and lived with his parents in cities across Europe, including Berlin and Paris, where he attended the prestigious Lycée Claude Bernard. The Lintons arrived in the United States before the outbreak of World War II. Leonard studied mathematics and physics at Columbia University before being drafted into the U.S. Army in May 1943.

Leonard volunteered to be a paratrooper in the elite 82nd Airborne Division commanded by the legendary general James Gavin. He first saw combat in January 1945, just after the Americans had beaten back the ferocious German attack through the Ardennes—the Battle of the Bulge. But the German Army still had plenty of fight left and Leonard was almost killed when his foxhole was run over by a Tiger tank. He was completely buried, but luckily for him, his helmet created a small air pocket. When other soldiers on American tanks saw his rifle sticking up from the ground’s surface, they rushed to dig him out.

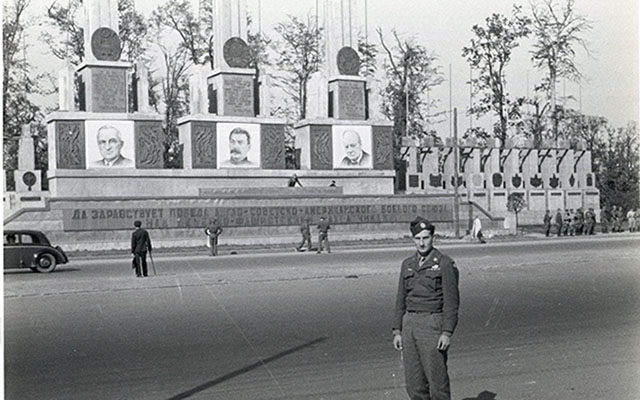

As the U.S. Army slowly advanced into Germany, Leonard’s fluency in German got him assigned to an Army Military Government school and then to a G5, a unit tasked with administering newly conquered territories. Since he spoke Russian as well, Leonard was ordered to prepare to act as a liaison with the Red Army, which was approaching from the east. As Leonard’s G5 unit advanced deeper into Germany, he met more and more Germans who all insisted that they had opposed the Nazis from the beginning, had done all they could to help Jews, and knew absolutely nothing about the ongoing atrocities.

Leonard’s anger at the Germans grew. Years later, he would recall one incident that filled him with shame. As he was enjoying an abundant meal of steak and potatoes, he realized that there was too much on his plate and he threw some of his food into a garbage bin. Starving young German children approached the garbage can but Leonard kept them from getting the food. “I hated their looks,” he said, “just because they were German and somehow responsible for the misery we saw.”

On May 2, 1945, Leonard was the first paratrooper to enter the town of Ludwigslust. He barged into the mayor’s office, where a meeting was underway, and let the Germans know in no uncertain terms who was now in charge. It was on that same day that he discovered the nearby Woebbelin concentration camp. Woebbelin, a subcamp of the Neuengamme concentration camp, had been established as recently as February 12, 1945. It was not a labor camp, and it seemed to have no particular purpose other than to house prisoners from other camps that were being hastily evacuated in the face of the advancing Allied armies. As Germany’s collapse accelerated, more and more prisoners entered Woebbelin from camps to the east and north, such as Auschwitz and Sachsenhausen. The inmates included common criminals, political prisoners, and Jehovah’s witnesses. Jews were in the minority.

Woebbelin was a lethal camp. Living conditions were appalling, there were minimal food rations, and the buildings were unheated and infested with vermin. Christine Schmidt van der Zanden, who has made a study of Woebbelin, contends that by the time Leonard would have arrived at the camp, a hundred inmates a day were dying of starvation and disease. There is no way of calculating how many prisoners passed through Woebbelin because not all transports were registered.

Leonard’s first reaction when he set foot in the camp was one of horror and disbelief. General Gavin ordered all the German civilians of nearby Ludwigslust, as well as prisoners of war, to walk by the mounds of corpses. They were also ordered to move corpses with their bare hands and transport them to a site where a military chaplain conducted a dignified burial service.

Leonard and his comrades did all they could to help the liberated inmates, but they made mistakes that led to additional fatalities, such as giving them food that was too rich for them to digest. Leonard learned as he went along. He commandeered a section of a nearby German military hospital and arranged for health care. He also made an informal deal with a nearby Red Army commander to trade oats for flour, which the G5 team used to provide the inmates with bread. After a few weeks, the Americans left Ludwigslust, which was transferred to the Soviet zone of occupation. Leonard then worked as a security officer for DP camps and participated in U.S. intelligence operations against the Soviets.

After the war, Leonard became a successful businessman and founded Central Resources Corporation, which sold chemical fertilizers worldwide. He also had a successful record in the oil and gas business and became a noted business consultant. In the years following World War II, Leonard visited Ludwigslust on many occasions and compiled a database of the Woebbelin camp’s former inmates. In May 2000, the town made him its first ever honorary citizen. Leonard Linton died in 2005 and was survived by his wife Catherine and three children.

———

Additional readings and information

Leonard’s unedited testimony can be found at the Fortunoff Video Archive (available at access sites worldwide): https://fortunoff.aviaryplatform.com/r/z02z31nz02.

###

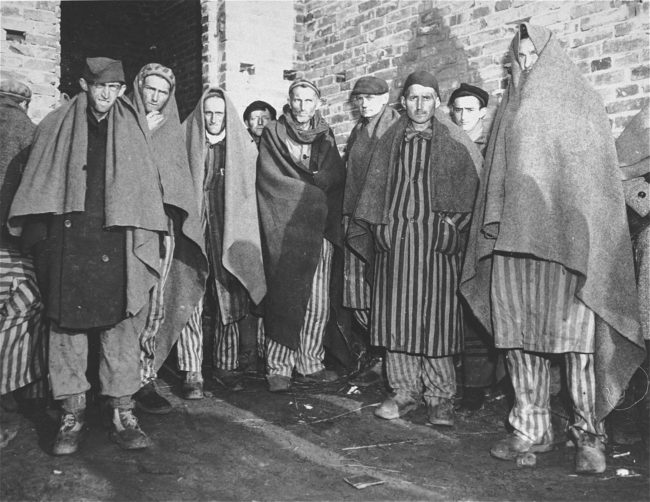

Leonard Linton: We saw some survivors in their striped uniforms—the stripes were supposed to be black and white, but, actually, they were dark gray and light gray.

I thought at first that a prison gate was opened, and some criminals came out. But quickly I learned that there was a concentration camp and that they were survivors.

I’m Leonard Linton, veteran of the 82nd Airborne Division, which has liberated the Woebbelin concentration camp in northern Germany at the end of World War II.

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Those Who Were There: Voices from the Holocaust,” a podcast that draws on recorded interviews from Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. I’m Eleanor Reissa.

Leonard Linton was born in Yokohama, Japan, on New Year’s Day 1922. His parents were Russian landed gentry who had fled the Russian Revolution. Leonard’s father struggled to find work in Japan, so in the mid-’20s, he moved his young family to Germany. As Hitler rose to power in the early 1930s, the Lintons moved again, first to Paris, and later to the United States.

By the time young Leonard landed in a New York City high school, he was fluent in English, Russian, French, and German. He was an avid photographer and served as president of his high school’s camera club.

After college, Leonard enlisted in the U.S. military, volunteering to serve in a combat unit toward the end of World War II.

Four decades later, Leonard is seated in a television studio in Union, New Jersey. It’s December 16, 1988, and Leonard is being interviewed by Bernard Weinstein.

Leonard wears a wide-lapelled, gray tweed sport coat. His thin, gray hair is combed straight back. Large, horn-rimmed glasses accentuate his square face.

Leonard talks about a day in the spring of 1945. The U.S. military was advancing toward Berlin and Leonard drove into Ludwigslust, a small city in northern Germany.

———

LL: I believe that I was the first trooper of the 82nd Airborne to come into Ludwigslust. In fact, I rushed into the town hall while a meeting of the mayor with all his administrators was in progress, and I barged in sort of rough and ready, threw my carbine on the table during the meeting, and asked them what was this meeting all about.

Bernard Weinstein: Were you by yourself?

LL: I was by myself. I was tired, dusty from maybe two days of Jeep riding, rushing as far and as quickly as we could. And I was certainly not in a very tender frame of mind near this end of the war. So they told me that the meeting was as to what to do in case the Americans arrive. So I told them the meeting is now ended because it’s no longer a question of whether or not we will arrive, we are here, and I’m taking over. And as representative of the 82nd Airborne military government, they are now under my direct command to do as I order them.

I stayed there maybe 20 minutes, certainly not even half an hour. I kept going because our orders were, go on to Berlin. And so I kept going in my Jeep. And a few kilometers outside of Ludwigslust, that’s when we learned about the existence of the Woebbelin concentration camp.

I drove there, and when I arrived, an incredible sight greeted me. You can imagine that a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne Division is a fairly hardened individual. However, when I came into this concentration camp, I must say that, to this day— and this was many years ago—an incredible and really undescribable disgust, a feeling, a mixture of horror, repulsion… I am not good enough in utilizing any language to describe this adequately.

However, there was this barbed wire enclosure with an open gate in front. So I left my Jeep in front of the gate, stopped the engine, and walked in. There were several people, most of them were men but there were a few women there also, maybe 20 or 30 people, milling around. Some of them were in fair shape, but most of them were emaciated, haggard-looking, almost ambulatory corpses.

I couldn’t understand why they were still milling around in front of this horrible camp. Of course, the German guards had all evaporated at our approach. And they simply said they didn’t know where to go. They were afraid of the outside world. They were afraid of the Germans. They were afraid of everybody.

BW: Were they young, middle-aged, elderly?

LL: The ages ranged… I would say the youngest were about 10, maybe 12, 13 years old—children, which they didn’t really look like children. They just looked like children to me because of their size, although they looked like the others, nearly dead. I saw some people—a few, very few—who might have been around 40. But the majority I would venture to guess were between 19 or so to about 30.

Now, as I talked with some of them, I was curious who they were, what were they in for. They said, “Well, I’m from Lithuania. I’m from Poland. I’m from Czechoslovakia. I’m from East Prussia. I’m from Belgium. I’m from France. I’m from Luxembourg.” They were from all over, all over Europe. In fact, in Woebbelin, unlike some of the other camps, the majority were non-Jews. So I was asking the non-Jews what were they in there for? So one of them said, “I was denounced by somebody.” “Denounced for what?” He sort of shrugged his shoulders. He doesn’t know for what. He was just denounced.

And one I met I remember very well. He was a doctor from Prague. And I asked him what was he there for. So he said, well, he was denounced because he treated a Jewish patient.

I had my camera at the time. But in the beginning, I couldn’t really think even of taking pictures.

There were several buildings, one-story barrack-like buildings. So I walked into the first one. I believe there were three or four tiers of wooden bunks. The bunks were, perhaps, a foot and a half, maybe two feet wide, and the length of a normal, average human being. Rough wood, with straw. And amazingly enough, there were people still alive in these bunks who were looking at me coming in without speaking, without uttering a sound.

Then I’d go to the next barrack, and I’d see the same sight. May have been 10 percent or so of the bunks were occupied, had people in them. Not all of them were alive. Some were obviously dead, must have died only a short time before my arrival there.

I saw in front of another building, against the building, a pile of corpses not very unlike firewood piled against a building. That’s more or less how they were stacked, perhaps not as neatly. They were just sort of piled one on top of the other with faces upside down in grotesque configurations, mouths open, eyes open.

As I was walking through there, one young fellow, a surviving inmate, accompanied me, and I was talking with him. And I would ask him, “Why are these people piled here?” So he said, “Well, we were just told to pile, to put them there and we put them there.” I would say, “Well, what were they doing with them?” He said, “Oh well, they made us dig a pit and after a few days with it, throw the corpses into that pit. And then they put a little bit of earth on top of them, layer by layer, until the pit would be full. And then they’d dig another pit and put—bury more. And these were just died in the last day or the last hours. And even they keep dying.”

Then we walked around, I remember I saw one corpse laying in the street sort of sprawled out. So I said, “How come he’s just laying there?” He said, “Yes, he was shot by the doctor.” I said, “What… doctor?” “Yes, a German military doctor who was there.” So I said, “Why did he shoot him?” He said, “Well, the doctor didn’t like that he looked at him. And the doctor pulled out his pistol and shot him for that.”

I have to also mention another feature that is unforgettable about this camp, which, to this day, still nauseates me. That is the odor. This was in May in northern Germany. The day was beautiful—clear, a little nippy. Not a warm day. But inside these barracks was a stench the likes of which I had never smelled before or after. Corpses rotting in the undescribable filth—in their fecal matter, in the urine, in the straw that was rotting. Their clothing were rotting. And no air cleaning this out.

I tried to speak little because I felt that I didn’t want to open my mouth too much, because I could feel almost the particles of that smell getting on my lips and, when I talked, getting into my mouth. It sickens me when I think of it to this day.

I finished my visit, and I had to drive back to town, to Ludwigslust. I accelerated the Jeep on that road pretty fast. I remember I was holding the wheel in my hand and leaning as far out as I could from the Jeep and opening my jacket, my vest, to let the wind clean me out. But for several days after that, I felt that my uniform smelled, that I smelled, that my boots smelled. Of course, I changed uniforms immediately. I went through five, or six, or maybe 10 showers, and I couldn’t get that smell out of me. It was, of course, in my mind. But it was horrible.

BW: Was, was the reaction of others similar to yours?

LL: Practically identical. Our disgust was not just with these physical conditions. We were appalled at the Germans for doing this to people. That a highly sophisticated nation of educated people like the Germans could sink to such behavior?

In 1933, when Hitler was making his demented speeches, I was only a young kid. I could already understand that this guy was completely crazy. Nevertheless, we saw that the German nation submitted. In fact, in my opinion, did more than submit. They yelled him into power, thinking that Germany will be great again by bringing this madman into power.

And so when we saw this concentration camp, we didn’t have to be told in the 82nd Airborne about the non-fraternization policy which the United States Army had. We didn’t want to shake a German hand. We didn’t want to smile at a German.

Of course, I stayed on in military government for two years after the war ended, and I realized that there were countless Germans who were really powerless to do much. The German secret police was really quite efficient.

As a slight interlude, I might add that one thing that I did—how small the world is, really—the railroad station of Ludwigslust was not bombed. And I looked at it quickly. There was nobody in there. And I thought this was a good spot where to bring a couple of the survivors who I felt needed to be nursed back to life.

One thing we had learned is that there comes a point in their life when they don’t want to live anymore. They look right through you with these sad, huge eyes. They don’t care about anything. There is nothing worse than that because you can’t cope with it. And they will die even though they’re free.

So a small group of French survivors in this camp—two of them were in fair shape, and one or two of the Frenchmen were not. They were going to die within a day or two. So I told them, “Why don’t you take them in the railroad station. I’ll bring you food. And see if you can help this friend of yours.”

And indeed, after a few days, they nursed this fellow back from almost corpse-like appearance to where this fellow, his eyes were focusing and looking at my eyes. And then he asked me, “How come you speak French like that?” So I said, “Well, I went to Lycée St. Bernard.” He said, “I went there, too.” We realized we were in the same class. He did not recognize me, and I certainly did not recognize him. But we were in the same class. What a small world.

BW: Do you talk a great deal about it today?

LL: Not so much, I must say. What… In the last few years, I met a group of survivors from Woebbelin. We became acquainted. When I see them, I’m happy to see that there are still people alive. But what amazes me is that so few of them are vengeful. I am more outraged personally at what the Nazis have done, and I would like to see bloody revenge if possible, at all, against the guilty, than the survivors themselves.

But talking about the principle of collective guilt, I am not sure whether something like what the Nazis did cannot happen anywhere under different circumstances. In every nation, there are brutes [or, “they’re brutes”].

———

ER: When Leonard Linton found the Woebbelin concentration camp, there were one thousand unburied corpses, and hundreds more bodies buried in mass graves. There were no gas chambers or crematoria in Woebbelin. Prisoners were worked to death and died of starvation and disease.

In the weeks that followed, Leonard and his fellow American soldiers forced the Germans—both civilian and military—to give all the victims a proper burial at a Ludwigslust castle. He also helped set up medical care for survivors until they were repatriated.

Leonard stayed in Germany for two years, working in Berlin as part of the U.S. military government. After he returned home, he built a global fertilizer business, married a Russian émigrée, had three children, and settled in Point Lookout, New York.

Leonard Linton died in 2005. He was 83.

To learn more about Leonard Linton, please visit thosewhowerethere.org. That’s where you’ll find additional background information and photographs Leonard took during his army service.

To hear more from “Those Who Were There,” please subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. You can also go to thosewhowerethere.org.

“Those Who Were There” is a production of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, which is housed at Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Department.

This podcast is produced by Nahanni Rous, Eric Marcus, and the archive’s director, Stephen Naron. Thank you to audio engineer Jeff Towne and to Christy Tomecek, Joshua Greene, and Inge De Taeye for their assistance. Thanks, as well, to Sam Kassow for historical oversight and to our social media team, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Ljova Zhurbin composed our theme music.

Special thanks to the Fortunoff family and other donors to the archive for their financial support. I’m Eleanor Reissa. Thank you for listening.

###