By Dr. Samuel Kassow

Martin Schiller, born in 1933, was a small child living in Tarnobrzeg (Dzikev in Yiddish), a small town in southeastern Poland. According to the 1931 census, of Tarnobrzeg’s 3,643 inhabitants 61 percent were Jewish. Until the German invasion of Poland in 1939, Martin had a happy childhood. Along with his older brother, he grew up in a close-knit, religious family. By the standards of the time, they were well off.

When the war began, the Schillers’ world rapidly collapsed. Martin was barely six. In October 1939, the Germans expelled the Jews from Tarnobrzeg and the Schiller family settled in the nearby shtetl of Koprzywnica (Pukshivnitse in Yiddish). For a time, they hid on the property of an acquaintance whom they quickly came to distrust. In the fall of 1942, when the family’s money had run low and mass deportations to the death camps were in full swing, Martin’s parents made a critical decision: to enter a German labor camp, in this case the HASAG ammunition factories at Skarzysko-Kamienna.

Readers might wonder why Martin’s family—with full knowledge that the Germans had begun the mass murder of Jews—would voluntarily enter a German camp. But what alternative did they have? While it is true that almost 7,000 Poles were recognized as “Righteous Gentiles” for having risked their lives to save Jews during the war, most Jews who tried to hide were rightly convinced of two things. First, they could not survive without the help of Poles. Second, the overwhelming majority of Poles were indifferent at best; at worst, they were all too ready to denounce Jews or fellow Poles who tried to help them. In this episode, Martin expresses his bitterness at the Poles, both for their wartime attitude and for the antisemitism he encountered when he returned to Poland in 1945. This was an attitude shared by a majority of survivors. The fact that Martin’s parents saw a German camp as offering their best chance of survival speaks volumes about what it was like to be a Jew in German-occupied Poland in 1942.

According to Felicja Karay, in the 32 months of Skarzysko’s existence, about 20,000 Jews were brought to the camp and 14,000 died there. Starvation, typhus, and terrible working conditions took a heavy toll. There were constant selections as weaker prisoners were taken to a nearby forest and shot. Martin’s father was killed.

How did Martin beat the odds and stay alive? Terrible as it was, Skarzysko was better than many other camps. Since it produced 30 percent of all the German infantry ammunition for the Eastern Front, it was a vital cog in the German war machine. HASAG’s director, Paul Budin, was a ruthless Nazi who cared nothing for Jewish life. But he was a skilled political operator whose wheeling and dealing kept the ultimate authority over the complex in the hands of HASAG, not the SS. When the SS murdered 43,000 Jews in nearby labor camps in early November 1943, the HASAG camps were not touched.

Jewish labor was cheap and Budin was ready to look the other way and admit even children like Martin and his brother. Martin also had another bit of luck. He was sent not to Werk C, which was a mini–death camp, but to Werk A, where the conditions were a little better. And though still a child, Martin grew up fast. He developed a keen instinct for survival. Martin got another prisoner to teach him how to run a vital machine and became valuable to the HASAG operation. Conscious of his status as a skilled worker, Martin felt emboldened to risk his life and ask his German supervisor to save his mother and brother from imminent execution. When Skarzysko was evacuated in the summer of 1944, Martin and his brother were sent to Buchenwald while his mother ended up in a camp near Leipzig.

In Skarzysko, as elsewhere, the Germans used the prisoners themselves to keep order. Kapos, a network of privileged prisoners, had a lot of power and did not hesitate to use it. Often life or death depended on which prisoner you knew, or how well you were able to play the black market or steal materials from the factory. In one of the most revealing parts of Martin’s full, unedited testimony (not included in the podcast episode), he recounts an incident when 20 former kapos and policemen were lynched by their fellow prisoners after they arrived at Buchenwald in the summer of 1944.

Liberation was a bittersweet experience for Martin, as it was for many survivors. Martin recalls how the camp experience had made him tough, selfish, and callous. He tried and failed to understand why this had happened, why there had been so much gratuitous brutality and so little kindness. Martin and his brother managed to find their mother, but their world had been totally destroyed. Now they had to decide where to go. A return to Poland brought a shocking reminder that Jews were not wanted there and indeed risked their lives by staying.

Although Martin prepared to go to Palestine, the family’s plans changed when in 1946 his uncles in America sponsored their immigration to New York. The well-meaning uncles enrolled Martin in a yeshiva, where he had another traumatic experience. Some of his classmates did not believe him when he talked about his wartime sufferings. One said, “Tell us some more of your bullshit stories.” As a result, for many years Martin only spoke about the Holocaust to fellow survivors.

What Martin endured during the war might easily crush any adult, let alone a child. His is a story of terrible suffering and of ongoing trauma. On the other hand, his story also reflects a strong will to live, great resourcefulness, and, as is the case with all survivors, some lucky breaks. Of the more than three million Polish Jews who found themselves under German occupation (not counting the 300,000 who were deported or fled to the Soviet Union), no more than 60,000 survived—in hiding, in camps, or with false papers. Martin lost 66 relatives. But he, his brother, and his mother, incredibly, survived.

———

Additional readings and information

Karay, Felicja. Death Comes in Yellow: Skarzysko-Kamienna Slave Labor Camp. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic, 1996.

Schiller, Martin. Bread, Butter, and Sugar: A Boy’s Journey Through the Holocaust and Postwar Europe. Lanham, MD: Hamilton Books, 2007.

Martin’s unedited testimony at the Fortunoff Video Archive (available at access sites worldwide): https://fortunoff.aviaryplatform.com/r/x639z90q20.

A 2013 interview with Martin at the Yiddish Book Center: https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/collections/oral-histories/interviews/woh-fi-0000434/martin-schiller-2013.

Martin’s website, with a link to a documentary produced by his son: https://www.martinschillerauthor.com/.

###

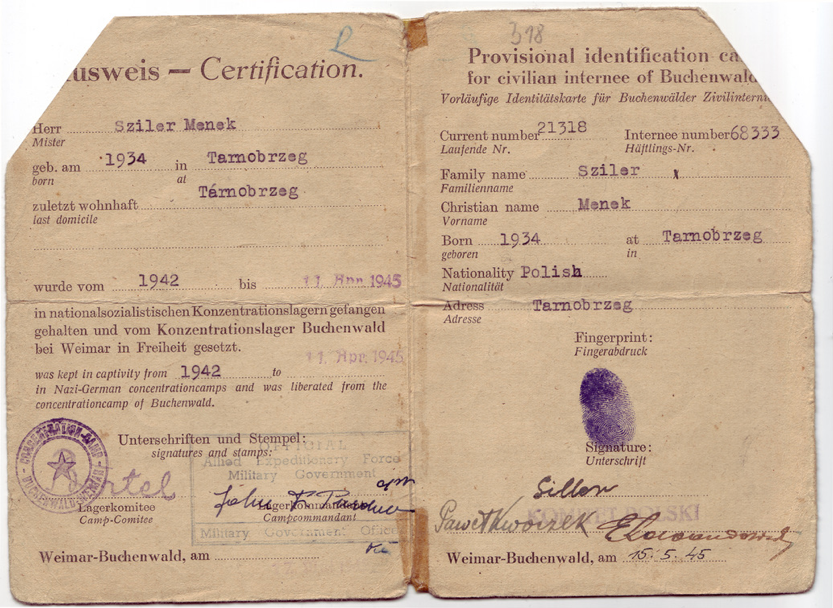

Martin Schiller: My name is Martin Schiller. I was born in Poland in a town called Tarnobrzeg. I was born in 1933. However, old records show that I was born in 1934. One of the things that happened during the war, particularly in labor camps, was when you gave your age too low, then you weren’t productive enough. It was not worth feeding you, because we couldn’t produce. So you always made yourself older. We played so much with our ages during the war that we literally lost track.

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Those Who Were There: Voices from the Holocaust,” a podcast that draws on recorded interviews from Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. I’m Eleanor Reissa.

Martin Schiller was from Tarnobrzeg, a small town in southern Poland. Before World War II, the majority of the population was Jewish, but few survived the war. More than 60 members of Martin’s family perished. It’s now January 3, 1986, and Martin Schiller is sharing his memories with interviewers Susan Millen and Ellen Suesserman in a TV studio in New Haven, Connecticut. Martin is 52 years old. He’s heavy set, mostly bald, with piercing blue-gray eyes. He’s wearing a navy blue suit and gestures with his right hand as he speaks. Martin remembers when war first came to Tarnobrzeg. It was 1939, and Germany had just invaded Poland. Martin was six years old.

———

MS: I remember the war coming to our town with a very severe air raid. The whole city was just an inferno. And we all ran for our lives. We crossed a river called Vistula. And certain things you can remember. And one of the things I remember is we were crossing in a little boat. We just looked at a wall of fire in back of us.

Interviewer: Do you remember what life was like before the war?

MS: Yes, I had just begun kindergarten. It was this small town type of life where we had our own circle of friends. We had a very happy home. Living in our home was my mother, my brother, I, my father, and one set of grandparents. But in the same town there were many, many more. We were a very religious family. So holidays were always wonderful, because family got together. I remember the Purim plays. We were always involved in it. And I was particularly a happy child, my mother keeps telling me. But it all came to an abrupt halt immediately. It was around November ’42 that we went into a labor camp. As soon as we got into the camp, I knew we were in trouble. Anybody that didn’t get off the truck fast enough was hit over the head with a whip, kicked. My father, my brother, and I were taken in one direction. My mother was immediately put into another camp. They put us into a, a barrack that must have held three, four hundred people. And there were layers of beds made out of wood. And all you had was straw. We were given this area to sleep in, which was the three of us… The width of that bed was probably the width of this couch.

Interviewer: What did you think when your mother was taken to another camp?

MS: It was traumatic, sure. I was particularly attached to my mother, so it was devastating, I would say. How old was I then? Eight years, eight and a half years old. But interestingly enough, there was a sudden instinct of survival that, quite frankly, I didn’t dwell on it. I attribute my survival to this instinct. Because I saw children just falling by the wayside, people dying. As a matter of fact, I trained myself to be very brutal, very cold. And oftentimes I, I, uh, I have some… I guess I can’t ask them to turn this off, can I?

Interviewer: If you like.

MS: No, no, keep it running. It should be documented. I sometimes think I was made too inhuman. Because I didn’t care about anybody else. And, uh, that was the very early lesson I learned, that when you were given your piece of bread you hide it. And if a man is begging you for a piece, I did not give it up. It was within a matter of months my father took ill and he could not go to work. And generally the word was, you’ve got to go to work, because if they find you in there…

They had a sport, if someone became sick and he said, “I’m all right, just I want to rest one day,” they’d say, “Well, okay, see if you can run a straight line.” And they told them to run in a straight line, but they were firing bullets on either side of that line so that if they couldn’t hold the line… And that’s what happened with my father. I just went on. My brother and I just… We clung to each other.

Interviewer: Did you work together in the same camp?

MS: Not— No. He worked in one area, I worked in another. I was put on a machine that made bullets, shells. As a matter of fact, I attribute my survival to the fact that I was able to hustle and then to overcompensate, because they would come and inspect and they would say, “What is this child doing here?”

So before long, I was literally running four machines by myself with most people running single machines, only to prove, you see, that I am worth it. I became what they called a model prisoner. And mine was a stop on inspections to show the Germans, look at what a tremendous producer he is.

Well, I began feeling guilty, because everybody tried to do something to hurt the German war cause. Now, a shell is held inside the rifle. But if you make the cut that holds the shell too shallow, when you fire it, it jams the gun. So one of my practices to sabotage was to adjust the cut whenever I thought they weren’t going to check, so that it would jam the rifles.

Now the Germans obviously recognized that sabotage would go on. So they would come around periodically and check. One day I must have piled up boxes and boxes of these poorly made shells. And I picked up my head and I saw an inspector coming. And I immediately adjusted it. And there must have been thousands and thousands of shells in there. And by the time he got to me, maybe I spit out 20, 30 that were good. I was lucky he picked up one that was good.

Interviewer: Do you remember how you felt?

MS: Oh, the fear was unbelievable. I thought I had had it.

I don’t think there was ever a week that went by when you didn’t feel, this may be it. It was one of those situations that you always kept looking over your shoulder. You always had to think 10 steps ahead. You always had to plan. What if? What if? I can remember one time, my mother and my brother, and about 12, 14 other people were being taken into the woods—that was common—to be shot. Someone came running to me and told me. And I ran over to this guy who I thought was my best pull. Because I was such a good worker, you do get a little pull, no matter how bad they are.

They were already shooting two or three people. See, what they would do is one at a time. And I began pleading and begging him: “The only thing I’ve got left in this world is my mother, my brother. Please help save them.” Oh, I remember begging.

He yelled out a command, “Halt!” Halt. And they stopped. And he said to me, “Which ones are yours?” And I pointed to them. He just pulled them out of the line. They went back to work. And that was it.

Uh… There was a period of time that I walked around—I would say that was the first year—I just kept asking, Why? And I couldn’t get the answer. I remember I walked by a spot and a guard hit me very hard over the head. After I recovered—because he did put me into sort of a semi-conscious state for a few minutes—I turned around, I said, He doesn’t know me. I wasn’t even thinking of the fact that I was a child. He doesn’t know me. I don’t know him. Why does he have such a hatred for me? Those things used to gnaw at me.

Interviewer: Would you like to go back and talk about the day of liberation? Do you remember that day?

MS: Yes, I remember.

Interviewer: OK.

MS: I remember it very distinctly. It was April the 11th, four o’clock in the afternoon. I remember it as clear as a bell. This was in Buchenwald. I remember the Americans coming in. When the war ended, it was just my brother and I. And here we were liberated. Didn’t know what to do with ourselves.

Interviewer: Where was your mother at that time?

MS: She was—all we knew was that she was in a place called Leipzig. We didn’t know whether she was alive. But we knew we had to head in that direction.

Interviewer: Just by yourselves?

MS: Just by ourselves. Never having traveled—remember, we went into the camp at eight. I was eight, my brother was nine. We jumped on a truck. And because everything was bombed out—rails were down, bridges were down—it was a pretty tortuous trip.

Every time we came to a city, people that got out of camps would give their names. “Have you heard of so-and-so?” You looked at the lists and so on. You’d always leave your name. We had been told that they were killed—everyone was killed—but we didn’t accept it.

We ended up in a town that someone told us she was in. And we stepped off the train. It was just fresh after a rain. And there’s a lady who was walking with a kid in a carriage. And she says to us, “Are you by any chance the Schiller children?” It was just unbelievable. We said, “Yes.” She said, “I’ll take you to your mother.” And that was it.

That meeting, we couldn’t, we couldn’t break apart. We just held on. It was in a hallway that was six stories, and I can remember people coming out of the doors and watching us and we just couldn’t let go. Holding on and crying.

We went back to Poland. But when we were in Poland, we were there no more than a week or two and there was a pogrom. Oh, god.

Interviewer: After liberation?

MS: After liberation, after the war. We went back, we didn’t even want to make, lay claim to anything. We just wanted to look for our families. We were in Krakow. In that two-week period we were there, there were two pogroms.

It was so shattering. Here I’m coming back from what I call hell, and I remember saying to myself, You know, when we get back to Poland, they’re gonna feel sorry for us. They’ll open the doors for us. And we arrive in Krakow, and we’re waiting in one of those holding areas for the DPs, and they’re attacking with guns, knives. It was terrible. The Russians were protecting us.

After things settled down, it quieted down, and they’re standing there with their machine guns, two other Russians walked by. And one said to… The two that were walking by were hollering up to one of them, “What are you doing up there?” He says, “Oh, I got duty, I’ve got to watch these kikes.” That jolt.

It was at that time that I was convinced, Israel—at that time was Palestine… After the two pogroms, plus this—the utter helplessness, the, the feeling of despair… Is there any place that I don’t have to fear? Is there any place that I can feel comfortable?

We got out of… I remember my mother went through the whole war with her wedding band. I don’t know how she did it. We got to the Polish border, they don’t want to let us out. “Poland not good enough for you?” And my mother began arguing. And he says, “I’ll let you through if you give me the ring.” That was the parting shot with Poland.

Now I got thrown off the track, so I don’t remember what I was leading up to.

Interviewer: You were talking about going to Israel, looking for your family.

MS: We arrived in the United States, not in Israel—Palestine then—simply because we had a couple of uncles—three uncles—who were able to find us in the DP camps and were able to send us visas to come to the United States.

When we arrived, they said, “We’re going to send you to a yeshiva.” And I didn’t want any part of a yeshiva. I mean, I didn’t believe. I… I was on the opposite end. I was hateful. But they reasoned with us. My uncle said, “Look, you can’t speak a word of English. You’re thir—going on 13. You’ll never be able to make it in a regular public school. If we put you into yeshiva, at least you’ll be able to communicate with people. There is an affinity between Jews. They’ll be able to understand and give you a little more room and more time.” And they said, “And if you don’t want the religion, throw it away. Play the game.” So we agreed.

One of the things I remember as a child coming out, I felt I had to tell the world what was happening. So I remember the first few months in the yeshiva I would speak freely. I would tell the kids everything. I would tell my rabbi what happened and so on.

Then one day we went out on recess and one of the kids got ahold of me. We were all in a circle. And he said, “Why don’t you tell one of your bullshit stories.” And from that day on—this was 1946, ’47—I did not say a word, I would say, till about five, seven years ago.

I used to say after the war, thank god it didn’t affect me. But, oh my god, it, it made its mark on me.

———

ER: Only after Martin Schiller’s children started asking him questions did he begin to talk about what had happened to him during the war. In 2004, at his son’s urging, Martin returned to Poland for the first time. Despite his reluctance to go, he says that in some ways it was a catharsis. However, he says, the nightmares and flashbacks have never entirely fallen away. Out of Martin’s entire extended family in Poland, only he, his brother, mother, and a cousin survived the Holocaust. Now, in his mid-80s, Martin lives with his wife in Delray Beach, Florida. They’ve been married for six decades and have three children and five grandchildren. To learn more about Martin Schiller, please visit thosewhowerethere.org. That’s where you’ll find additional background information and photographs, as well as a link to Martin’s autobiography and his son’s documentary about their trip to Poland.

To hear more from “Those Who Were There,” please subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. You can also go to thosewhowerethere.org.

“Those Who Were There” is a production of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, which is housed at Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Department.

This podcast is produced by Nahanni Rous, Eric Marcus, and the archive’s director, Stephen Naron. Thank you to audio engineer Jeff Towne and to Christy Tomecek, Joshua Greene, and Inge De Taeye for their assistance. Thanks, as well, to Sam Kassow for historical oversight and to our social media team, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Ljova Zhurbin composed our theme music.

Special thanks to the Fortunoff family and other donors to the archive for their financial support.

I’m Eleanor Reissa. Thank you for listening.

###