By Dr. Samuel Kassow

Like many Holocaust testimonies, Judith Perlaki’s story is a reminder that survival depended on luck and, quite often, on being able to maintain family bonds even in the worst of circumstances. After the war, as Judith was raising a family of her own in the United States, she decided to tell her story to high school students and to do what she could to ensure that the Holocaust would not be forgotten. But despite her sufferings, she cautioned against the dangers of bitterness and hate.

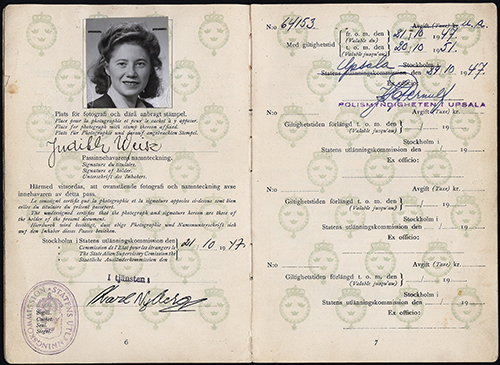

Judith Perlaki, née Weisz, was born in Nagyrozvágy, Hungary, in 1925 into a religious Jewish family. Her father was a relatively wealthy wheat merchant. Judith was especially close to her mother’s parents, who lived in the same town. Her grandfather, who was extremely devout, ran a tavern. There were six children—five girls and a boy—of whom three survived the war: Judith and her sisters Elizabeth and Lily. Their father also survived, although they did not learn this until 1946.

Nagyrozvágy was located in Hungary’s Zemplen region, a multiethnic area that, according to the census of 1900, had a population of 327,000 people, of whom 10 percent were Jewish. After World War I, when Hungary lost 80 percent of its territory, the northern part of Zemplen became part of Czechoslovakia. Nagyrozvágy remained in Hungary, but it was close to the Czechoslovak border; Judith recalled that her father had property in Czechoslovakia (today’s Slovakia) and made frequent trips there.

By the time Judith was born in 1925, the “golden age” of Hungarian Jewry had passed. During this golden age, which lasted from 1867 until 1914, Hungarian Jewry had prospered, enjoying full equality and extensive economic opportunities. By 1914 Jews constituted a large part of the Hungarian middle class and owned much of the country’s industry. To be sure, the Hungarian nobility that ruled the nation excluded Jews from their social orbit, but they nonetheless made Hungarian Jews feel that they were an integral part of the country.

This close partnership between the Hungarian elite and the Jews rested on two pillars. The first was the major contribution Jews made to the Hungarian economy. The second was the indispensable role of the Jews in Magyarizing the vast tracts of Hungarian territory that were not ethnically Hungarian, including present-day Slovakia, Transylvania, and large parts of Croatia. Indeed, grateful for the recognition and support they received from the Hungarian nobility, most Hungarian Jews became avid patriots, “more Magyar than the Magyars.” Zionism made few inroads in Hungary proper, and even religious Jews, like Judith’s family, were more inclined to speak Hungarian than Yiddish. When Judith remarked in her testimony that she was a real Hungarian patriot, she was expressing what most Hungarian Jews felt at the time.

However, by the time Judith was born in 1925, the Hungarian Jewish honeymoon had come to an end, although the era of intense persecution had not yet begun. The Treaty of Trianon had stripped Hungary of 80 percent of its pre-World War I territory, including Slovakia, Transylvania, and Croatia. As a result, Jews had lost their former importance as defenders of Magyar language and schooling in these regions. In addition, the short-lived 1919 Communist dictatorship of Bela Kun, a Jew, had led to a violent counter-revolutionary backlash and, with it, a sudden outburst of vicious antisemitism. And with Hungary’s territory and economic potential greatly reduced, the massive Jewish presence in industry and the professions also sparked a backlash. (In 1920, half of all lawyers and 60 percent of all doctors were Jewish; in 1930, 60 percent of all firms employing more than 20 employees were owned by Jews.)

Judith had a stable and secure childhood in Nagyrozvágy, but her father and grandfather would certainly have begun to worry about the escalating calls to curtail the outsized Jewish presence in the Hungarian economy. Once Hitler came to power, more and more Hungarians began to look to Germany as the only possible ally in their quest to recover the lands lost after World War I. As Germany’s popularity grew, so too did calls to emulate the Nazis’ ruthless approach to the “Jewish Question.”

By the late 1930s a new dynamic had developed in Hungarian politics. The conservative political elite began to feel increasing pressure from the radical right. The latter, grouped around such organizations as the Arrow Cross, began to demand tough measures to eliminate Jews from the economy and eventually force them to leave the country. In response, the conservative right, fearful of losing ground to the radicals, passed the first anti-Jewish law in 1938, which was succeeded by harsher anti-Jewish laws that eliminated Jews from 80 percent of the economy.

Hungary’s anti-Jewish laws were accompanied by a conscription decree that forced Jewish men, including Judith’s father, into “labor battalions.” Largely employed on the Eastern Front, where the Hungarians fought the Soviets alongside the Germans beginning in 1941, the Jews in these labor battalions suffered a very high mortality rate due to malnutrition and dangerous assignments like mine-clearing. Thanks to his connections and his expertise with horses, Judith’s father was able to persuade the Hungarian authorities to let him perform his labor service at a horse farm close to home. But Judith’s family could not entirely escape the consequences of the new laws: her grandfather lost his pub, while the army confiscated her father’s horses. Meanwhile, local thugs had begun to throw stones through the windows of Jewish homes.

Nonetheless, despite the growing antisemitism and persecution, until 1944 Hungarian Jews were in a much better position than Jews in neighboring countries. They lived in their own homes, continued to worship in their synagogues, and managed to make a living in spite of economic oppression. This certainly seems to have been the case for Judith’s father and grandfather. Judith herself continued to attend a Hungarian high school in a larger town nearby until 1942, when she was 17. Remarkably, even when millions of Polish Jews had already been murdered, most Hungarian Jews seemed largely oblivious to the “Final Solution.” Judith mentioned having heard rumors, but she also remarked that, as their deportation train rolled on towards Auschwitz, it was only her aunt who bleakly warned that they were all going to their deaths.

It remains startling that between May 15 and July 7, 1944—so late in the war, when German defeats had removed all doubt about the final outcome of the conflict—Nazi Germany, enjoying the enthusiastic connivance of Hungarian authorities at all levels, was able to ship 437,000 Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz. Moreover, while the deportations were halted on July 7 just short of Budapest, the mass murder of the remaining Hungarian Jews resumed in October 1944 as another 100,000 Jews were killed.

Beginning in 1938, Hungary’s deepening alliance with Nazi Germany had drawn handsome dividends, enabling the Hungarians to recover large swaths of territory lost at Trianon, including parts of Slovakia, Carpatho-Ukraine, and northern Transylvania. Hungary became Hitler’s ally, and Hungarian units committed anti-Jewish atrocities in Yugoslavia and Ukraine. Nonetheless, until 1944 the government, headed by Regent Miklós Horthy, rebuffed German calls, supported by the Arrow Cross, to deport Hungarian Jewry, even as it passed more antisemitic legislation.

Everything suddenly changed in March 1944, when a furious Hitler summoned Horthy to an acrimonious meeting where he accused him of sending peace feelers to the Allies behind his back. Hitler told Horthy that Germany would immediately occupy Hungary and install a new government headed by Döme Sztójay, a fascist and rabid antisemite. Horthy remained as regent, but he now went along with German demands—including the mass deportation of Hungarian Jews. That same week, SS “Jewish expert” Adolf Eichmann arrived with a trusted team to start negotiations with the new Hungarian government. Together they quickly prepared a plan to expropriate Hungarian Jewry, force them into ghettos, and load them on trains to Auschwitz. The Hungarian civil service and gendarmerie lent their wholehearted cooperation. The Catholic Church made a few noises about Jewish converts to Catholicism but otherwise kept silent.

One might ask how Hungarian Jewry allowed itself to be trapped and murdered so late in the war. Didn’t they know where they were going? What about the Hungarian Jewish leadership? One should remember, however, that while Hungarian Jews had become used to antisemitic persecution, they still refused to believe that the Hungarian government could betray them to the Germans. After all, hadn’t they shown over and over again their loyalty to Hungary? Furthermore, opportunities for resistance were limited. Most young Jewish men were in the labor battalions. Hungarian society was hostile, or at best indifferent. Judith recalled that a Christian friend offered to help her avoid deportation, an offer she rejected because she did not want to separate from her family. But such an offer of help from a Hungarian neighbor was rare indeed. In the end, what could Hungarian Jews have done? Where could they have hidden? Once Horthy betrayed them, they were trapped. To quote Yehuda Bauer, “They were caught on an island in shark-infested waters, and they had no boat. If the island was flooded, they were doomed.”

In her testimony, Judith recalled that when a girl suddenly appeared with the news that the Germans were in Budapest, she was met with disbelief. All the Jews were busy baking matzos in preparation for the approaching Passover holiday; it simply did not occur to them that their time had run out. On April 15, 1944, the Jews of Nagyrozvágy were suddenly thrown out of their homes, loaded onto wagons, and transported to the Sátoraljaújhely ghetto about 20 miles away. Severe overcrowding meant that 15 to 20 people had to share a single room. There was insufficient water. Judith’s grandfather died in that ghetto, spared the horrors of deportation.

Judith and her family arrived in Auschwitz in May 1944, after enduring a nightmarish train journey. No sooner had they stepped off the train than prisoners in striped jackets—the “ramp commando”—began to tell girls who were carrying children to give them up. Judith was carrying her little sister Edith and was selected to follow her mother in the line to the gas chambers. But at the last minute, her mother took Edith and told Judith to join her two sisters who had been selected for work. It is not exactly clear how Judith managed to change lines—doing so was usually impossible—but she did.

Judith and her sisters stayed together, in Auschwitz and at subsequent camps—a major reason why they survived. In Birkenau they were first enlisted in field labor and then put to work in the so-called Kanada warehouses, enormous buildings close to Crematoria IV and V where the belongings of the deported Jews were sorted. Work in the Kanada warehouses was highly coveted since it gave prisoners a chance to find food as they went through the deportees’ possessions. Judith also used the opportunity to engage in acts of passive resistance, such as throwing gold, jewelry, and other valuables down the latrine rather than handing them over to the Germans. But the location of Kanada meant that Judith had to see unending lines of people marching into the gas chambers.

Judith’s testimony reinforces other inmate recollections of Birkenau: tensions among different groups of prisoners, the callous attitude towards new arrivals, the thin line between life and death (e.g., during an outbreak of scabies, Judith was mistakenly selected for the gas chamber but managed to convince an SS man to let her go). On the other hand, some of Judith’s assertions echo widely held but erroneous beliefs shared by Auschwitz inmates. For example, there is no evidence that the Germans made soap out of dead bodies. Nor is there any record of anyone (with one exception) coming out of the gas chamber alive. But Judith’s memory of the huge open-air pits where the Germans burned bodies in the summer of 1944 is absolutely correct: so many Hungarian Jews were arriving in Auschwitz that the existing crematoria could not cope.

(While Judith indicated in her testimony that she left Auschwitz in September 1944, the fact that she remembered Yom Kippur in Birkenau as well as the Sonderkommando revolt of October 7, which blew up the camp’s Crematorium IV, meant that she must have left Auschwitz sometime in October 1944.)

As Germany’s demand for slave labor escalated in late 1944, Judith and her sisters were transported from Birkenau first to Bergen-Belsen and then to SS-Reitschule in Braunschweig, one of the Neuengamme subcamps. This contingent from Bergen-Belsen included some 800 women, mostly Hungarian Jews, and arrived around Christmas 1944. As Judith testified, conditions in the camp were frightful; indeed, SS-Reitschule had the highest death rate of the entire Neuengamme system. The prisoners’ work—clearing rubble and making airplane parts—was grueling and performed without adequate winter clothing.

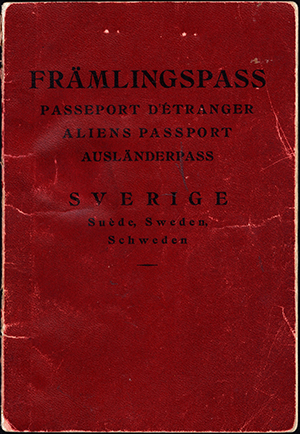

In 1945 Judith and her sisters became the beneficiaries of a Swedish initiative to rescue concentration camp prisoners. SS Chief Heinrich Himmler, anxious to launch peace talks with the western Allies and save his own skin, agreed to a proposal by Swedish diplomat Count Folke Bernadotte to allow prisoners to be transferred to Swedish jurisdiction and evacuated to Sweden. Originally slated just for Scandinavian prisoners, the initiative—which became known as the White Buses mission, after the distinctive transport vehicles it deployed—eventually rescued more than 15,000 prisoners, including many from Hungary and Poland.

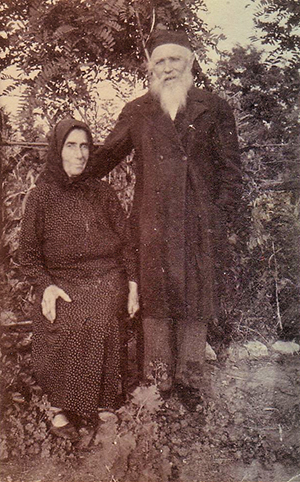

Once in Sweden, Judith and her sisters began to rebuild their lives. To their great surprise, they learned that their father had survived the war and remarried. While conditions in Sweden were good, none of the sisters stayed there. Judith and Elizabeth immigrated to the United States, Lily to Israel. During her immigration processing, Judith met Thomas Perlaki, a survivor from Budapest. They married and had two children, Lawrence and Diane, as well as four grandchildren.

Judith Perlaki died on May 7, 2010. She was 84 years old.

———

Additional readings and information

Judith’s unedited testimony at the Fortunoff Video Archive (available at access sites worldwide): https://fortunoff.aviaryplatform.com/collections/5/collection_resources/2605.

Braham, Randolph L. The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary. Condensed ed. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2000.

Fenyvesi, Charles. When the World Was Whole: Three Centuries of Memories. New York, NY: Viking, 1990.

###

Judith Perlaki: I’m Mrs. Perlaki, born Judith Weisz in a small town of Hungary called Nagyrozvágy. One day two gendarmes comes in and I’m sitting in the backyard and one of them tells me, “I ripped my pants. You sew it.” I said, “Okay.” I took a needle and thread. I sewed his pants—into his underpants. So my mother was begging me, “Please, you are risking your life.” I just didn’t believe it.

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Those Who Were There: Voices from the Holocaust,” a podcast that draws on recorded interviews from Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. I’m Eleanor Reissa.

Judith Perlaki grew up in a well-to-do religious family. She attended public schools until she was 12, then a private high school. After Judith graduated, her mother sent her to a tutor to learn how to sew. Her mother explained that if she could afford to buy nice clothes, she should be able to judge the quality of the sewing. And she wanted Judith to have a useful skill because you never know what life brings.

In 1944, when Judith was 19, she and her six younger siblings, her mother and father, and other relatives were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp.

It is now March 8, 1993, and Judith Perlaki is being interviewed by Joni-Sue Blinderman at the offices of the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City. Judith is wearing a broad-shouldered blue jacket with a colorful striped scarf tied at the neck. Set off against a black backdrop, Judith’s crown of curly silver hair frames her round face.

Judith picks up the story with their arrival by cattle car to Auschwitz after a grueling multi-day journey.

———

JP: Uh, they opened the doors and we saw, uh, prisoners. They had striped uniform and a striped cap on it. And they were whispering, uh, “Let the children go, let your children go,” in Jewish. We didn’t understand it. Why? Some people did; some people, uh, some mothers would not let their children go, that’s for sure. Well, get off the train, I was holding my little sister’s, uh, hand, one of the younger sister hand.

And they separated the men immediately from the women—“This way, that way.” Uh, when—I looked young and my, uh, I was holding a little, my little sister’s hand, German asked me, “Frau oder Mädchen? Are you a married woman or are you a girl?” And I said, “Frau,” because I had a little kid in my hand. He shoved me to my mother’s side, where my mother was. Meanwhile, my two younger sister was put on the other line, so my mother pushed me out, she said, “You go there and take care of your two sisters, and don’t forget, obey the Sabbath day.” That was the last thing I heard from my mother.

So, uh, I went, I sneaked back to my other two sister. My mother grabbed the little one from me, my little sister. And I went on the other side to, uh, my other two sisters. And at that point, we didn’t know why they said that, “Let the children go.” Later on we found out why. Because if you were a healthy young woman, uh, and you had a child in your hand, you went in the crematorium line. If you didn’t have no child, your life might be saved because you are strong enough to work.

The only thing, uh, what they told us right away in the barracks, those people who were there long before us, uh, “If they wanna tattoo you, go, don’t hide from tattooing. It might be, uh, uh, you save your life.”

So when they called us out, uh, we went out to be tattooed. And my sister, uh… I am 1933—uh, six-nine-three-three—my younger sister is 34, and the middle one is 35. Later on, I’m gonna to tell you the story how this number saved, uh, my middle sister’s life.

A couple of days later, they supplied us with white kerchiefs on our head. We looked like nurses. So we stood in line that they gave us the white kerchiefs and he said, “You are gonna go to work.” And they started to march us to work. Where, we didn’t know. Anyway, uh, we had to pass a gate where music was playing. Musicians was playing, and on the door it says, “Arbeit macht das Leben süß, work makes, uh, the life sweet.”

And then we went into a very, very big warehouse and right across the street was the big chimney, the gate to the chimney. The thing was a gate, but it was all covered with blankets. We could not see inside what’s going inside. The only thing we started to hear is the prayers, the crying, screaming.

When we went into that warehouse, which is right across from there, and, uh, we smelled the smell. We heard the yelling. And they took us into the big warehouse. He said, “You put everything, uh, separately. You put the eyeglasses, the shoes, the clothes, definitely jewelry and the money—that’s separate, and you give it to us.”

While I was, uh, getting all the stuff together, I cut into one of the long robe, a button with a scissor, and I discovered they were all wedding bands, gold wedding bands. He must have be a jeweler who wanted to hide, uh, his jewelry. He covered it as, you know, button on a long dress. From then on, we started to look for the jewelry or the money. And we didn’t have no bathroom. We had a big latrine outside.

We already had the brains to, what we could get away with it, not to give it to the Germans. We threw it in the latrine. If anybody ever digs up that latrina, it’s a lot of gold and diamonds are laying there, and money definitely ’cause we use the money for toilet paper.

Joni-Sue Blinderman: How many—were there only women working in the warehouse?

JP: Only women.

JSB: Only women.

JP: Only women. The men was working in the, uh—

JSB: The crematorium.

JP: Crematorium.

JSB: And how many women would be working a shift?

JP: Hundreds and hundreds.

JSB: So it’s a huge, huge—

JP: A huge warehouse, was a very huge warehouse. I mean, we had everything had to be separated. So the coats go to here, the glasses goes here, the boots, the artificial feet goes there, and everything had to be in separate… And of course the jewelry and money—the German was fast to take it. They took it. I mean, they weren’t so honest about it. They took it for their own, uh, use.

JSB: And would there be suitcases and so on in there, or had they…?

JP: Yes. Oh, sure.

JSB: They’d be closed-up suitcases?

JP: There were closed up-suitcases. And there we found, we found food, and we found all, uh, kind of different things so that because we were not undernourished.

JSB: The, um, the crematorium warehouse was in close proximity also to the gas chambers as well as the crematorium? Was all…

JP: The crematorium and the gas chamber was in one, uh, unit. It was, uh, top and bottom. They took the clothes from there to us to be, uh, separated.

JSB: And did you have a view of people being, uh, marched into these areas?

JP: Oh, to march in, yes.

JSB: What did you see, what was the…?

JP: We saw a, a big transport, just like we came in, with a lot of people. They’re going in the gate. We never saw them coming out.

JSB: Were the men and women together?

JP: Men and women together. At that time, there were men and women together, old and young.

JSB: And the young children.

JP: And children, children by the thousands.

Also, I forgot to tell you, in the crematorium I found my little sister’s clothes, my youngest one, and my aunt’s clothes. My sister’s dress, I was hiding it for months. How I lost it, I still don’t know. I did not take my aunt’s, but I recognized my aunt’s clothes and my younger sister clothes. I had it with me. I was hiding it.

We worked at night and we passed the shift was coming in the morning, because in the morning the men came into the crematorium to work inside of the crematorium. All of a sudden one guy recognized us. He was from one of our nearby town from Hungary. And between the German soldiers and the dogs, he slipped us a note that, “Find my two sisters.” So happened, the two sisters of his was in that camp. So we saw them and we said, “We saw your brother going into work in the crematorium.” And my sister Elizabeth, she was very, very daring. She took notes from the sisters to give it to the brother the next day when we passing them by. She managed it, she gave the notes.

One day we went back to the camp. Two sisters are not there. So we ask, “Where are they?” They said, “The black car stopped.” The black car meant that when the crematorium wasn’t too busy, then they chose right from the people right in the camp and also women who were pregnant when they came in. What they didn’t notice it they were pregnant because they were in the early months, but they started to show later on so they know they were pregnant. They took them out or, uh, on the Zählappell, every tenth one they took out and they burned in the crematorium.

So we went in and we asked for it. She said, “The black car stopped.” It meant the black going straight to the crematorium. So now how are you going to say to the brother? My sister wrote to him notes: “We couldn’t find your sisters, they went out to field work, they went here, they went there, went there.” A couple days later, he hands back a note to my sister: “You could stop lying. I put them myself into the oven.”

We were going into work one day when an old man pushed, uh, the blankets aside by the crematorium, and he was folding his clothes and he’s tied his shoes together. He thought he’s gonna come back to find his shoes. And it stuck in my mind. It stuck in my other sister mind, and the third sister mind. That scenery, none of us forget it.

Was one Sunday when the Germans came for inspection Krätze. The Krätze was a very bad outbreak of, uh, pimples. It’s itches like nobody’s business. My sister Elizabeth was loaded with it. The whole body was loaded with the Krätze. The German came up and they wrote up her number. The next day, we know she’s going up on the chimney. When they came, it says, “Nine-five-three-five.” They call, “Nine-five-three-three.” Her “five” looks like my “three.” So instead of “five,” they wrote up “three,” my number.

They call for the call, and they call me. So, uh, I went outside and, uh, right there where the cars were already waiting, I said, figured I don’t have nothing to lose, I said, “Herr Oberscharführer, ich habe keine Krätze nicht. Herr Oberscharführer, I don’t have this.” So he told me, “Halt deine Schnauze [?], verfluchter Jude. Shut up, you Jew bastard.” I still don’t have nothing to lose. I said, “But I don’t have any.” He said, “Take off your rags.” He didn’t have to tell me twice. I took off my rags. And he was amazed because not a spot on my body. So he said, “No, she doesn’t…” He said, “Lauf zurück, run back.” He didn’t have to tell me twice. I run back to the camp. At night time my sisters returned from work with swollen eyes, of course, from crying because they figured I’m up on the chimney already. And that was, uh, the second time I beat death, because the first time, when my mother pushed me, this is the second time I beat death.

So we stayed in, uh, Birkenau till fall time. When we went to, uh, Bergen-Belsen, Bergen-Belsen was, comparing to Auschwitz, heaven! The treatment over there, it wasn’t as harsh as in Birkenau. It was a lot, uh, a lot more lenient. So gave us a little bit of more hope.

JSB: Now you left, uh, or you were taken from Bergen-Belsen in December ’44 by, by cattle car to Braunschweig?

JP: That was already in January 1945.

JSB: Yeah, yeah, that you arrived in Braunschweig. How many of you were in this group that came out of Bergen-Belsen to Braunschweig?

JP: To Braunschweig, from, uh, around 600. We remained about two; 400 died. You couldn’t, uh, endure that, that cold, that, the, the mistreatment, everything else—they were falling one after the other. And we weren’t too sorry because the ration became to us.

JSB: Where is Braunschweig?

JP: Braunschweig’s in Germany. We cleaned the streets—no clothes, no shoes—in a snow. No place, uh, to go, any warm place, because the only place we slept, it was a big barn. No covers, just straw. So the body heat from each other kept us warm.

Outside of Braunschwig—Braunschweig—was a very big salt mine. They transferred us to work in a salt mine, but the lift took us downstairs. It wasn’t just a salt mine, it was—they were manufacturing parts to airplanes. It was actually a factory underneath in that salt mine.

Over there, uh, remarkable things happened. A German soldier—he wasn’t the Nazis, he was a Wehrmacht, he had a Wehrmacht uniform on it—uh, he spoke to me, a German, he found out that I speak German. And my sister was so young, Lily, every single day he brought her, her sandwiches to eat on the QT, he was giving it to her on the side. And he was telling me in German, “Don’t worry, not too long. They’re, they’re coming in, the English are coming, the Americans are coming.” He was giving me… So I felt, why is he telling me all these things?

One day he came in, he said, “Before 12 o’clock, all of you, go to the bathroom. Don’t forget, go to the bathroom.” So I listened to him—after all, he was bringing sandwiches to my sister. We all went to the bathroom. There was a big explosion in that factory. At that point, I knew he was a German spy. He was a German but he was a spy. And, uh, after that, uh, explosion, we never saw him again.

We came out from Braunschweig in, uh, April. We were constantly on the, uh, on the go. So we were a long time, we are up on the train and down on the train. And that was the time when we are on a big field, had to have about two thousands of us, and machine guns in the middle, machine guns all around it. And I, we heard when the German officers said, “I can’t do it. These are two thousand innocent people.” He must have a good idea already that he’s getting close to the end of the war and they lost it. Because we saw a guy with a mo—a soldier with a motorcycle handling, uh, over some kind of papers to him, and he packed up his machine guns, and he said, “Get up, back on the train.”

So they were taking us from one place to another. And finally we arrived to Denmark. They opened the doors. We saw blue uniforms. And also a German soldier came up on the train, and he said in German, “What’s new?” He asked the guy who was with us in the train, “What’s new?” He said, “Nothing special. We lost the war and Hitler is dead.” Well, after things, you don’t think you believed him! Because we figured it’s one of their, uh, cute tricks.

And then came up all this uniformed men with the Red Cross uniform. You would see the lice walking up and down on the blue uniforms because we are full of lice.

They took us to a big, big—it looked like or a warehouse or a barn or something where tables were set, with spoon, forks and knives, and plates. We didn’t see none of this for a, for a year. And they served us something to eat—with coffee, with drinks, and everything else. Now included me, we putting all the food into the—underneath our clothes for tomorrow because we still didn’t believe there we are free. We figured maybe it’s one of their tricks also.

On the same night, they took us into Sweden by boats to Landskrona. And officially came to on the radio that Hitler is dead. The war is over.

We arrived in Sweden. What it’s—uh, amazingly, in one, uh, procedure, they de-liced us. Then they took us to a warehouse where it was mostly American-donated clothes. Picture me weighing 68 pounds. And I choose a very tight-fitted black skirt, with a scalloped red blouse on it, a beret on my head, and a heel this high, and my feet are full of frostbites. I couldn’t even walk in them. But to me that was so beautiful. I mean, after all…

So we stayed there till, uh, ’46, and I started to work in a factory, the coat factory in Uppsala. And night time I went to the university, I started to study back, and I learned the language very fast. So it started, uh, life started to be back normal in Sweden.

I could go on and on and on and tell you stories, but still I think about it, still I—some of them, I can’t believe it if it was possible to live through.

JSB: Uh, if there’s anything, uh, that you’d like to say before we complete the interview, any last comments…

JP: Well, the interview I would like to, uh, remind the people, please don’t forget it. Don’t let us be forgotten. Because it was there and anybody who tries ever to say it wasn’t there cannot face the world, can absolutely not face nobody because it was there. It happened. Very unfortunately, it happened. I was there. I have a number on my arm. I—that my youth was taken away, my mother and my sisters were taken away. It happened. It was there. So don’t let anybody to defy that. Believe us. And thank you.

JSB: Thank you very, very much.

———

ER: In 1948, Judith and her sister Elizabeth immigrated to the United States. Their sister Lily went to Israel. Judith settled in Brooklyn, where she met and married Thomas Perlaki. They later moved to New Jersey where they raised two children. Judith worked as a seamstress at a local clothing store and Thomas commuted to Manhattan to wait tables at a restaurant across the street from the Waldorf Astoria hotel.

In 1991, Judith traveled with her sisters and her son Lawrence to Auschwitz and Hungary. “They were very anxious to touch the fence at Auschwitz,” Lawrence recalled, “the one that was electrified when they were imprisoned there. We also took a walk through the barracks and they told stories about what it was like.”

In later years, Lawrence often went with his mother to speak at schools about her experiences during the war. “We went a half a dozen times a year for 15 years,” Lawrence recalled. “My mother’s favorite school was Eastside High in Paterson, New Jersey, because the kids, who were mostly Black and Hispanic, were of course subject to racism themselves.”

Lawrence said that the phrase his mother always repeated at their school talks was, “If you fill your heart with love, then there’s no room for hatred.”

Judith Perlaki died on May 7, 2010. She was 84 and was survived by two children and four grandchildren.

To learn more about Judith Perlaki, please visit our companion website at thosewhowerethere.org. It includes episode notes, a full transcript, and archival photographs. That’s where you can also find our previous episodes, as well as background information on the Fortunoff Video Archive and the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

“Those Who Were There” is a production of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, which is housed at the Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Department in New Haven, Connecticut. This second season is a co-production with the Museum of Jewish Heritage—A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, New York’s contribution to the global responsibility to never forget. The museum is committed to the crucial mission of educating diverse visitors about Jewish life before, during, and after the Holocaust.

This podcast is produced by Nahanni Rous; Eric Marcus; the Fortunoff Archive’s director, Stephen Naron; and Treva Walsh, collections project manager at the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

Thank you to audio engineer Jon Gordon. Thanks, as well, to Christy Bailey-Tomecek, Joana Arruda, Noa Gutow-Ellis, and Inge De Taeye for their assistance. And thank you to Sam Kassow for historical oversight, and to photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael Leclerc, and our social media producers, including Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Sara Barber. Ljova Zhurbin composed our theme music. Thank you, as well, to Judith Perlaki’s children, Lawrence and Diane, for providing archival photographs and background information.

Special thanks to the Fortunoff family and other donors to the archive for their financial support.

I’m Eleanor Reissa. Thank you for listening.

###