By Dr. Samuel Kassow

Renee Hartman was born in 1933 in Bratislava (Pressburg in German, Poszonyi in Hungarian). She had a younger sister, Herta, born in 1935. Their parents, like Herta, were deaf. Their father was a jeweler.

This is the story of two young children who were raised in a loving, religiously observant home and who experienced the traumatic and sudden destruction of their childhood, the loss of their parents, and their own deportation to the notorious Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, from which they were liberated by the British in 1945. As they struggled to stay alive, Renee and Herta were inseparable. No matter how depressed and distraught she became, Renee never forgot that her younger sister, unable to hear, totally depended on her. Together they survived a long nightmare that included betrayal, physical violence, life-threatening disease, and hunger.

During the time when Renee and Herta were born, the Jews of Bratislava lived in relative peace and security. Before World War I, most Jews in Bratislava had spoken Magyar or German (German was the language in Renee’s home). Between the wars they also had to learn Slovak as Bratislava, formerly under Hungarian administration, became part of the new Czechoslovak state, which was founded in 1918.

Under the leadership of President Thomas Masaryk, Czechoslovakia was a democracy, and somewhat more prosperous than countries like Poland and Hungary. Nonetheless, there were serious problems on the horizon. In 1930 Czechs accounted for barely half of the 16 million citizens of the republic, which they shared with three and a half million Sudeten Germans; three million Slovaks; 650,000 Hungarians; 745,000 Ruthenians; and 350,000 Jews. The Sudeten Germans became increasingly Nazified in the 1930s, and Hitler used their alleged sufferings as a pretext to destroy the Czech state.

The Slovaks, who claimed Bratislava as their capital, were another source of potential danger to the republic. While they were ethnically and linguistically related to the Czechs, there were also many differences that divided them. The Czechs tended to look down on the Slovaks, who were more rural, more devoted to their Catholic faith, and less developed economically. In turn, many Slovaks resented the Czechs, and they bore a special animus towards the Jews. Unlike the Czechs, the Slovaks had been under Magyar rule in the pre-war Habsburg Empire, and the Jews in these regions preferred German and Magyar to Slovak, which they saw as a backward peasant dialect. This provided a pretext for Slovak antisemitism. And while the Czechs had developed a strong and viable middle class, in the Slovak regions, the middle class was often heavily Jewish. Serious problems between Slovaks and Jews lay just beneath the surface.

Although Hitler had promised at the Munich Conference in 1938 to respect Czech independence once he got the Sudetenland, he broke that pledge in March 1939 when he sent German troops into Prague. This time his stated goal was to maintain order and to support Slovak independence. While the Czech lands became the German-ruled Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, the leaders of the antisemitic Slovak People’s Party, Father Josef Tiso and Vojtech Tuka, proclaimed the First Slovak Republic, which from the very beginning remained a close ally of Nazi Germany.

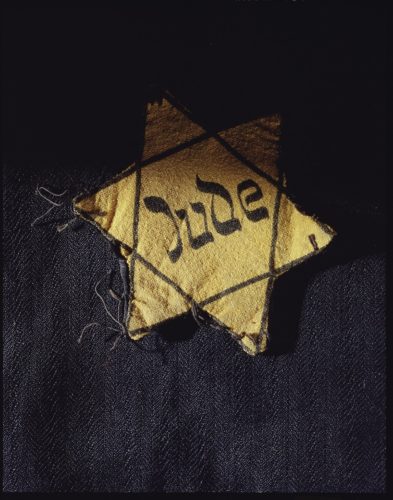

The new Slovak state quickly began persecuting its 90,000 Jews, who comprised about 3.5 percent of the population. The lure of Jewish property proved tempting to large sections of the Slovak population. The government expropriated Jewish businesses and purged Jews from the civil service, the free professions, and educational institutions. The Jewish Code of 1941 tightened these restrictions and forced Jews to wear the yellow star. On the other hand, the Catholic Church, while fundamentally antisemitic, protested the application of racial rather than religious criteria in anti-Jewish legislation.

In early 1942, the German government asked the Slovaks to send workers to the Reich; the Slovak leaders countered with an offer to deport Jews in their stead. The Slovaks even offered to pay the Germans 500 Reichsmarks for each deported Jew! Between April and September 1942, about 57,000 Slovak Jews—two-thirds of the total Jewish population—were deported to Poland.

Bribery and personal contacts enabled 16,000 Jews to secure various exemptions that saved them from this first round of deportations. Renee’s father had also obtained an exemption, probably because he was a skilled jeweler and goldsmith who reworked confiscated Jewish jewelry into Catholic religious objects.

Meanwhile, Rabbi Michael Dov Weissmandel and Gisi Fleischmann, one of the few women to become a genuine leader during the Holocaust, created a semi-clandestine organization called the Bratislava Working Group that bribed Slovak leaders and even negotiated with the main SS representative in Slovakia, Dieter Wisliceny. Their efforts—along with pressure from the papal nuncio and the misgivings of many Slovak leaders who had become aware of the Final Solution—seemed to produce results: in September 1942, the deportations were halted.

Neither Renee nor Herta was old enough at the time to remember exact dates or to offer a clear chronology of their wartime experiences. Even after the deportations ceased in the fall of 1942, the remaining 24,000 Slovak Jews lived in constant fear that they would resume. The Germans increased pressure to restart the deportations and some radical fascists within the Slovak leadership agreed. In the spring of 1943, there was much talk of sending new transports to Poland, but in the end that did not happen.

In 1944, however, the surviving Slovak Jews saw their reprieve come to an abrupt end. The outbreak of the Slovak National Uprising in August 1944 gave the Germans and the Slovak fascists the opportunity to pounce on the Jews and deport them. The Bratislava Working Group, meanwhile, had overestimated its bargaining power and understood too late that the new SS satrap, Alois Brunner, was determined to murder every last Jew in Slovakia. Fleischmann would perish in Auschwitz, Rabbi Weissmandel survived the war.

Most remaining Slovak Jews were sent first to the Sered’ transit camp and from there to Auschwitz. Several transports left for Auschwitz in September and October of 1944. After the destruction of the gas chambers and crematoria at Auschwitz in November of that year, subsequent transports from Sered’ were sent to other camps, including Bergen-Belsen and Theresienstadt. All in all, about 13,500 Jews were deported from Slovakia in late 1944; 10,000 died.

Sometime in 1944, Renee’s father had sent his two daughters to live with a non-Jewish farming family in the Tatra Mountains. But after a time, either because their parents stopped paying the family (Renee’s version) or because Renee demanded that they return home (Herta’s version), the two girls were sent back to Bratislava. When they got there, they learned that their parents had already been arrested. Unable to find a stable hiding place, and facing rejection from people whom they had considered family friends, a desperate Renee went to a police station and turned herself and her sister in. At first amused and then incredulous, the Slovak police sent the two girls to Sered’, where they learned that their parents had just been deported to Auschwitz.

It was probably sometime in November 1944 that the girls were put on a transport to Bergen-Belsen. (Just a few weeks earlier they would have been sent to the gas chambers of Auschwitz.) They ended up in a children’s barracks with mostly Polish-speaking children. Here, too, Renee did all she could to protect her younger sister, once even kicking a German doctor to keep him from taking Herta away for “medical research.” Renee remained hopeful that they’d be reunited with their parents and whenever a new transport arrived, she would call out their names. This once so angered a German guard that he hurled her against a rock and she temporarily lost her hearing.

By late 1944, conditions in Bergen-Belsen were rapidly deteriorating. Originally planned as a camp for “special” Jews who might be exchanged for German internees living abroad, by the second half of 1944, Bergen-Belsen had begun to receive many thousands of emaciated inmates from Dora-Mittelbau, Plaszow, Auschwitz, and other camps. Conditions became even worse when the notorious Josef Kramer was appointed commandant of the camp in December 1944. On his watch, new transports swelled the camp population from 15,000 in December to 60,000 in April. The inadequate food rations shrank even further and a typhus epidemic raged through the camp. Between February 1945 and the liberation, 35,000 prisoners died. Another 14,000 died after the liberation. Renee contracted typhus and barely survived.

After the war, the Red Cross sent Renee and Herta to Sweden. In 1948 American relatives brought them to the United States. These religious relatives received them warmly but, perhaps hoping to spare the girls, showed little interest in hearing about their experiences. Herta eventually went to the Lexington School for the Deaf in Queens, New York, where she thrived. She married, had three children, and spent many years working in data entry in banks. She now lives in Las Vegas.

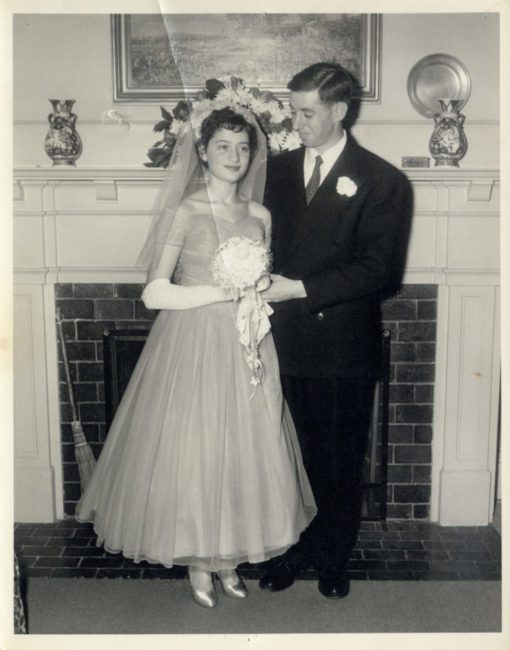

Renee moved to New Haven, Connecticut, where she studied library science at Southern Connecticut State College and became a librarian. She married Geoffrey Hartman, who was born in Frankfurt and left Nazi Germany on a Kindertransport in 1939. Geoffrey taught for 40 years in the Yale English Department, retiring as Sterling Professor of English and Comparative Literature. He died in 2016. The Hartmans had two children—a daughter, Liz, and a son, David.

Together, Renee and Geoffrey helped found the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale as well as Yale’s Jewish studies program. Renee has written extensively about the Holocaust, including a book of poetry, Wounded Angels, and a chapter on Bergen-Belsen in The Power of Witnessing, edited by Nancy Goodman and Marilyn Meyers.

———

Additional readings and information

Hartman, Renee. Wounded Angels. Porlock Press, 2007.

Goodman, Nancy, and Marilyn Meyers, eds. The Power of Witnessing: Reflections, Reverberations, and Traces of the Holocaust. New York, NY: Routledge, 2012.

Renee’s unedited testimony at the Fortunoff Video Archive (available at access sites worldwide): https://fortunoff.aviaryplatform.com/r/5t3fx73x7c.

###

Renee Hartman: I was a child during the war. When the Germans came into Czechoslovakia, I was not yet six years old. Things were not explained to me. Children, at that time, were kept in ignorance of much of what was going on politically or otherwise. And it was not possible to ask questions because every time you ask a question, they just give you a slap.

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Those Who Were There: Voices from the Holocaust,” a podcast that draws on recorded interviews from Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. I’m Eleanor Reissa.

Renee Hartman was born in Czechoslovakia in 1933, the same year the Nazis took power in Germany. By 1939, Renee, her younger sister, and her parents were living under German occupation in Bratislava—a city of 120,000 people, including 15,000 Jews.

Four decades later, Renee is settling into a comfortable high-backed chair, getting ready to be interviewed by Laurel Vlock and Dori Laub. It’s May 2, 1979, and the location is Dori Laub’s office in New Haven, Connecticut.

Renee is dressed casually in black slacks, a light brown knit top, and a beaded necklace. She has thick salt-and-pepper hair, and her large glasses reflect the bright lights used by the video crew.

As the conversation begins, Renee recalls a moment from her childhood when she realized her cherished freedom to roam the streets of Bratislava was being threatened.

———

RH: I remember coming home one day and seeing my mother sewing on the star on my coat. And I remember saying, “Let’s not do this because then we can’t hide.” And she said, “We have to. That is the decree.”

What happened in the town itself was the closing in of the neighborhood. We did not have a ghetto. And yet, there was a ghetto atmosphere there. Because what happened is that certain neighborhoods where Jews lived, which were more elegant neighborhoods, they were told they had to leave. So they had to move into a smaller and smaller enclave, the main street of which was Judengasse.

My mother had to take in about five or six people in addition to our family. We lived in a large apartment. So this was part of our sense that the community had to stick together.

Even though there were no gates, there were no wires, we were not welcome beyond certain streets. I had always been a child that used to roam around, to my parents’ despair. But so I got to know the city terribly well. And what I would do in order to be able to continue that sense of freedom that I had would be constantly to try to wear a scarf to cover up the Jewish star.

But I did feel that every exit into the town outside of my immediate home was into a very hostile and dangerous environment, that I always could be found out. And I would have fantasies about, what would happen to me if they found me out?

But the worst part for me at that time was watching the transports. And the transport would just suddenly appear. We would hear certain sounds of boots on the street. And, usually, whenever there was a transport, it was accompanied by 10 to 12 soldiers coming, marching together from house to house and gathering all of the people, knocking on the doors and saying, “You have an hour.”

And the transports used to terrify me, because the speed of them was so horrendous, where they were trying to force… They would yell at the people and say, “Get out, get out, quickly, get out! Gather together. You can’t take this suitcase, you can take this suitcase, only a little bit with you. No, you mustn’t take this blanket…” And they would just force the blanket away.

In the process also there would be a lot of hitting, especially of old people and of sick people and children. It was the behavior towards the very people that the Jewish religion says you must have a great deal of kindness, which are the sick, the old, and the children. And many of these people I knew very well. And I could imagine the kind of devastation that experience was for them.

Often what would happen is, if the whole family was not together, a child would be sent out to bring in the rest, try to… And that used to horrify me because there would sometimes be a child who would come running back, crying, “I don’t know where Papa is.” And so all these transports would get together on the street. And the people would wait there, hoping that the rest of the family would come. And eventually, what happened is that families were united at a central post because when the rest of the family came home and asked where they were, they would rush to the police station and immediately give themselves up to the Gestapo.

We lived on the fourth floor in the apartment. And my parents were both deaf. And I had a deaf sister. So I became the ears. I would have to warn them that the transport was coming. And what I would do is we would all rush in the back room. And when they knocked on the door, we didn’t answer. We were in the back room just trying to be as quiet as possible. And we used to live in terror of these boots.

As a result of this, the responsibility was on me to always hear what was going on because anytime I heard 10 boots marching down around the corner, I’d run immediately home, tell everybody to go into the apartment. And it got so that we all got to be very, very good in spotting. We developed eyes that looked for everything. And I was the ears.

In 1943, my family decided that they had to save part of the family. And so they decided to send my sister and me to a farm family out in the country, for which they paid great sums. And I had to hide the fact that I was Jewish. And I remember my mother taking all the stars off my clothes and sending me off.

I was taken by a person who was also deaf to his mother’s home in the countryside, somewhere near the Tatra Mountains at the foothills. I was told never to tell anyone I was Jewish. If the priest went by, I had to cross myself. It used to be terrible to do that for me because I felt that I was going to, in some way, have to pay for this. But I, nevertheless, knew that I had my sister as well to take care of, who was a year and a half younger than myself. They used to poke fun at my sister, who was deaf. And I would be very protective of her because I was really told to take care of her.

In the spring of 1944, the son came back to the farm and announced to me that my parents had failed to pay for the last five months of my stay there. And, consequently, somebody else was going to take care of us in Bratislava itself. He bundled us up, and we went back to Bratislava with him.

When we went back to Bratislava, there were various people we knew who had papers, forged papers. When we said, “Where are our parents?” they said they didn’t know.

I took my suitcase and my sister looking for a place to stay. And I would go to places where I knew people who were Christians. And I knocked on the door. And they slammed the door right in my face. We had no money. We were scrounging around, trying to find food. And finally I said to my sister, “We will die in the street, so we might as well just go to the police.” And I went to the police. And I said my name, and I said my parents’ name. And I said, “I’d like to join them.” They first laughed. And then they realized that I was perfectly serious.

I was immediately put on a truck and driven into Hungary. And that was in Sered’. I arrived there to discover that the… two weeks before my parents had been put on the train to Auschwitz. This was the first time I heard about Auschwitz.

And there was this very nice woman who immediately took me under her care. She said she was going to see what she could do for me, to make me join my parents again. And for two weeks, I was in Sered’ and she gathered food for me. She gave me two blankets. And she said, “Do not let anybody know you have that.”

Laurel Vlock: Say how old you were during all this time.

RH: At that time, I was nine years old. And I had my sister, who was seven and a half and to whom I had to explain everything, who had to be basically taken care of. Because she only knew the sign language. And I could sign with her, but she didn’t know how to communicate yet with the hearing people. And so I couldn’t ever lose sight of her. Because in the milling of the people, we could have been separated.

And we finally were put on the train. And I was told that I would be going to Auschwitz. And to me, of course, it was just an image of my rejoining my parents.

And it was a cattle car. And my sister and I sat on the suitcase the whole five days that we were in the train. And I, in some ways, was terribly relieved to be there. Because here I was among Jews again. They were all strangers. But still, the fact that they were Jews was very important to me.

During the whole process of our trip, we would have to stop because there was bombing going on. And at one point, it was so loud, and the car itself jumped tracks. And we were told that we would not be going to Auschwitz, that we would be rerouted. After about three days, we arrived in Bergen-Belsen.

And I remember the first night falling asleep. I had nothing to eat for a long, long time, nothing to drink. But I fell asleep. And I remember thinking life had played a terrible trick on me, because I wasn’t in Auschwitz with my parents. And I remember saying to myself as I fell asleep, I will never stop looking for them.

After being in Bergen-Belsen for about four to five months, I realized it was hopeless looking for my parents because the transports kept just coming in. And when I came to look at those transports, one of the soldiers who used to be very irritated with me all the time, especially when I started to ask, in perfect German, “Could I please call out my mother’s name?” I knew my mother couldn’t hear me, but I thought maybe somebody who knew that she was deaf would tell her that I had been calling out her name. And I would call out her name over and over again.

By doing that one day for about the fifth or sixth time, the soldier so lost his temper, he just picked me up and flung me against a stone. And I lost consciousness. And the immediate result was that I lost for, temporarily, my hearing, which was a sense of tremendous worry because I had to be my sister’s ears. I had to hear for her. But after about five or six days, my hearing came back.

Later on in Bergen-Belsen, I realized that my sister was being watched by the camp doctor. He would come by the children’s barracks all the time, come to my sister, pinch her cheeks, pull her ears, and try to be very friendly with her. And then one day he said to me that he would be able to give us oranges and chocolates if I allowed my sister to go into the hospital for a few days. And my sister was perfectly well. So I couldn’t understand why he wanted her in the hospital. And I just, uh, was very sassy, and I said, “No, you are not, because if you are, I’m going to kick you. I’m serious. I mean it.” And so he laughed and then forgot about it.

Later on, the Blockalteste told me that he had hoped to be able to use my sister for scientific research because he was very interested in the fact of her deafness. And one of the things we had always been told not to—even if we were very, very ill—never to go to the doctors because they were not to be trusted. And so we avoided it as much as possible.

At that time, there was the beginning of the typhus epidemic. And one thing I did receive from the woman in Sered’ was a small bag of tea, which I was able, during the time of the typhus epidemic, to exchange for a vaccine for my sister. And I was told it was a typhus vaccine. Whether it was one or not, I’m not sure. But the fact is my sister never did get the typhus. I did.

And so one of the saddest thing in my life has been that I have no recollection of the liberation because I was totally ill with the typhus. I was very near death. Had I had to wait another two days for the English, I would not have survived.

LV: Was your sister with you?

RH: My sister was with me. She had curiously survived the experience without illness, having turned into a very quiet, silent child and whose sense of the world was totally cut off. And during the time that I was sick, she had grown completely mute because there was no one to communicate with her.

One experience which I haven’t talked about was an episode which is the central episode of my life, which was when I was in the camp, I managed to find a roll of toilet paper. And I managed to also find, barter something I had for a pencil. And I was writing down everything that was happening to me. I was—about my longings, my fears, conversations I overheard, things people had said.

And at one point, this roll of toilet paper was found in one of the searches by the soldiers. And I remember coming back from the Appell, seeing a soldier sitting on the lower bunk with the toilet paper and rolling it and reading it to someone else and laughing and finding it very amusing. When I suddenly rushed up to snatch it, he pulled it away and he said, “No, this is too good for you.” And he took it with him.

And, of course, I heard the conversation, I heard what they were describing. One of the things that I remember him saying to the other was, “She has a wonderful sense of humor.” And I didn’t remember writing anything funny in it.

And I remember feeling, saying, You may have taken that toilet roll, but you haven’t stopped me from writing. And that was when I vowed that I would spend the rest of my life writing.

———

ER: After liberation from Bergen-Belsen, Renee Hartman and her sister were sent to Sweden, where they lived for three years at a facility run by the Red Cross. In 1948 an uncle brought them to Brooklyn, New York, and a year later they went to live with a foster family in New Haven, Connecticut. Renee later earned a degree in library science and went on to work for public libraries in Hamden and Fairfield, Connecticut.

Renee met her husband, Geoffrey Hartman, in the early 1950s. They married and had two children. Geoffrey was German-born and had been sent by his parents to live in England during the war. Together, Renee and Geoffrey helped launch the original video project that became the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. Geoffrey died in 2016.

Today, Renee lives outside New Haven, Connecticut, where she’s an active member of her local Jewish community. She’s an insatiable reader and true to her word, she never stopped writing. Her book of poetry, called Wounded Angels, was published in 2007.

If you’d like to learn more about Renee Hartman, please visit thosewhowerethere.org. That’s where you’ll find background information and links to additional resources.

To hear more from “Those Who Were There,” please subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. You can also go to thosewhowerethere.org.

“Those Who Were There” is a production of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, which is housed at Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Department.

This podcast is produced by Nahanni Rous, Eric Marcus, and the archive’s director, Stephen Naron. Thank you to audio engineer Jeff Towne and to Christy Tomecek, Joshua Greene, and Inge De Taeye for their assistance. Thanks, as well, to Sam Kassow for historical oversight and to our social media team, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Ljova Zhurbin composed our theme music.

Special thanks to the Fortunoff family and other donors to the archive for their financial support. I’m Eleanor Reissa. Thank you for listening.

###