By Dr. Samuel Kassow

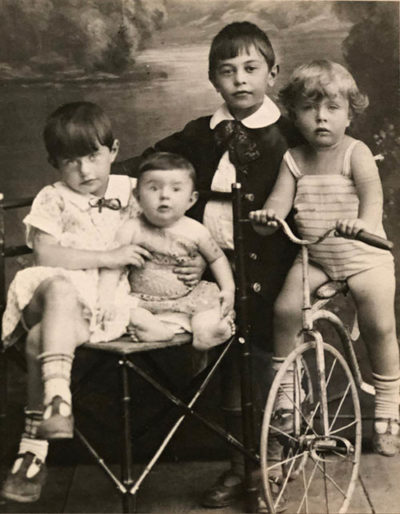

Isaac Zelig Zieman was born in Riga, Latvia, in May 1920 and grew up in the town of Līvāni in a traditionally observant family. In 1935, 981 Jews lived in Līvāni, out of a total population of 3,571. Līvāni’s Jews were shopkeepers and artisans, and they owned most of the stores in the center of the town. Isaac’s religious father ran a grocery store and was active in local Zionist politics. Isaac was the oldest of four children. He was the only member of his immediate family to survive World War II.

On the eve of the war, there were just under 100,000 Jews in Latvia—about 4.8 percent of the population. Half of them lived in Riga, the capital. Latvian Jewry, which had been under Tsarist rule before World War I, consisted of three distinct cultural groupings: Courland in the southwest; Livonia (which included Riga) in the northwest; and Latgalia (which included Līvāni) in the southeast, which was less developed economically. In Courland and Livonia, which had not been in the Tsarist Pale of Settlement, many Jews spoke Russian or German as their first language; Latgalian Jews, on the other hand, were proud members of the Yiddish-speaking Litvak tribe that spanned Lithuania, White Russia, and northeast Poland.

There was little social interaction between Jews and Latvians, and, as Isaac noted, Jews found Latvian culture, with its peasant roots, unappealing. Interwar Latvian Jewry, like Lithuanian Jewry to the south, nurtured a strong, largely self-contained Jewish identity reflected in Jewish political parties, schools, welfare institutions, hospitals, newspapers, and youth groups. Bundism and Zionism, along with the traditional orthodoxy of the Agudat Yisroel, were all strong. In a 1934 coup, Karlis Ulmanis established a semi-dictatorship in Latvia, and threw the government’s support behind the orthodox Aguda, which dominated Jewish political life on the eve of the war. While there was little anti-Jewish violence, antisemitism ran deep, and the slogan “Latvia for the Latvians” became increasingly popular.

In interwar Latvia the overwhelming majority of Jewish children attended Jewish schools, which were supported in part by the state. Isaac first attended Līvāni’s Yiddish-language elementary school (which later shifted to Hebrew) and then went to a local public high school that also had Latvian and Russian students. He was an excellent student and became an enthusiastic member of Gordonia, a Labor Zionist youth movement dedicated to the promotion of a pioneering kibbutz life in Palestine. While Isaac’s father was no religious fanatic, he demanded a level of observance and Talmudic study that Isaac refused to accept. Tensions between father and son grew more serious as Isaac grew older.

Isaac finished high school in 1937. His family could not afford to send him to university, so he entered a teacher’s college in Riga. In June 1940, just after Isaac had graduated, the Soviets occupied Latvia, along with the other Baltic states of Lithuania and Estonia. The new regime quickly established a ruthless dictatorship, carried out mass arrests, and nationalized the economy. The Communists shut down all other parties and youth movements, including Isaac’s beloved Gordonia. They also took over his father’s store. Just as Isaac was finally about to begin university, his parents asked him to return home to help support the family. He became a bookkeeper in a slaughterhouse—hardly the job of his dreams.

Latvian Jews received their new Soviet rulers with mixed feelings. On the one hand, Soviet economic policies ruined many Jewish families, while political repression and arrests shut down Jewish religious education and all Zionist and Bundist activity. On the other hand, new opportunities opened up for many young Jews: they could now get a higher education, and there were jobs in state and local government that had been off-limits before the war. The new rulers condemned antisemitism and offered the prospect of social mobility. And many Jews believed that, however bad the Soviets were, they were still better than the Nazis.

While only a small minority of the Jewish population actively supported the Communist regime, and although many Jews were among those arrested and deported by the Soviets, the perception that all Jews were Soviet sympathizers and betrayers of Latvia sparked a vicious backlash after the German invasion, reflected in large-scale Latvian participation in the robbing and killing of their Jewish neighbors.

The Germans attacked the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, and advanced so quickly that it took them only four days to reach the Latvian border at Daugavpils—a distance that took them four years to traverse in World War I. Only about 15,000 Latvian Jews were able to escape into the Soviet interior. Mass shootings began immediately and wiped out the Jews in the small towns of Latgalia during the summer of 1941. That’s when units of Einsatzgruppe A, aided by local Latvians, murdered the Jews of Līvāni in nearby shooting pits. After the last massacre on September 3, 1941, a sign at the entrance to the town proclaimed that Līvāni was “judenfrei.” A few Jews escaped to Daugavpils and Riga, where they were killed later. After the liberation in 1944, only seven Jews returned to Līvāni. Isaac lost his parents and his two brothers and sister.

In the chaos of the early days that followed the German invasion, Isaac had become separated from his family. Soon after, he found himself in a pick-up military unit on the former Latvian-Soviet border, where Soviet officials were turning back desperate Jewish refugees fleeing the German onslaught. Those who did manage to cross the border were usually cut off by the fast panzer divisions that could advance 50 miles a day. Fortunately for Isaac, there was a train that appeared just in the nick of time. It took him to Chelyabinsk, deep in the Soviet interior. Because he was already separated from his family, he was spared the agonizing choice between escape and staying with loved ones that cost so many young Jews their lives.

Like that of most Polish and Baltic Jews who survived in the Soviet Union, Isaac’s story is both fascinating and harrowing. His survival was a combination of luck and grim determination, aided by the help he received at critical moments from Soviet Jews. His experiences—long train journeys without food, grueling labor in a coal mine without adequate clothing or footwear, a short stint as a teacher in a remote Kazakh village, the grim conditions in the labor battalions of the Red Army—were comparable to those of thousands of other Jewish refugees. The hardship took its toll. Isaac worried that he had lost his humanity and struggled to hold on to his values.

Isaac showed a striking degree of agency in his determination not only to survive, but also to be able to leave the Soviet Union after the war. While Latvian and Lithuanian Jews could not leave the Soviet Union when the fighting stopped, Polish Jews could. A small number of Latvian and Lithuanian Jews, Isaac among them, managed to finagle fake documents that stated they were Polish citizens. The papers enabled Isaac to join the pro-Soviet Polish army of General Berling, leave for Poland, and eventually make his way to the DP camps of the American zone in Germany.

A key reason why Isaac’s testimony is so significant is that it deals with a very important, yet relatively neglected aspect of the Holocaust: the 350,000 Jews from Poland and the Baltic states who spent the war years in the Soviet Union. Many of these had been arrested or exiled before the German invasion; others, like Isaac, were able to flee with the retreating Red Army. The Jews in the wartime Soviet Union endured terrible privations—starvation, disease, exposure to harsh winters without adequate clothing, the casual neglect of callous and incompetent local officials—and most of the young Jews who joined the Red Army were either dead or wounded by the end of the war. Nonetheless, between 200,000 and 250,000 Polish and Baltic Jews in the wartime Soviet Union—or about 60 percent—survived. For the Polish and Baltic Jews who were under German occupation the survival rate was about 2 percent. By 1947, the vast majority of Jews in the displaced persons camps had spent the war years in the Soviet Union, not under Nazi rule.

Like so many other young DPs, Isaac found himself adrift, torn between his fervent Zionism and his desire to resume his education. He fought depression, married and divorced, and in a striking departure from the usual DP experience, he underwent psychoanalysis and then decided to make it his career. After his studies at the University of Zurich and the Munich Institute of Psychotherapy, he treated “hard cases,” DPs who did not leave the camps and who stayed in Germany until the last camp, Föhrenwald, closed in 1957. Isaac remarried in Germany in 1955 and arrived in the United States in 1957, where his two children were born.

Isaac was determined not to let his depression and the trauma he suffered in the war deflect him from his dedication to decency, empathy, and reconciliation. While he remained a staunch Zionist, he rejected Jewish nationalists who refused to recognize Palestinian suffering. In the early 1960s, Isaac met the eminent psychologist Ruth Cohn, who developed the concept of Theme-Centered Interaction (TCI), a humanistic approach that stressed the interplay of human autonomy and social interdependence. From that point on, Isaac found his true calling: he became a leading practitioner of TCI, and taught workshops all over the world, including workshops that brought together the children of Nazis and of Holocaust survivors. Isaac Zieman died of pancreatic cancer in 2007.

———

Additional readings and information

Isaac’s unedited testimony at the Fortunoff Video Archive (available at access sites worldwide): https://fortunoff.aviaryplatform.com/collections/5/collection_resources/1777/.

###

Isaac Zieman: My name now is Isaac Zelig Zieman. The name has changed throughout my life. Ah, I was born Zelig Zieman. I was born in Riga, the capital of Latvia, in 1920, 70 years ago, and the Latvians at that time were very nationalistic, and they wanted all names to, ah, be Latviasized. So my name became Zellicks Ziemanis.

When the war ended and I was leaving Poland, ah, to go to, um, Czechoslovakia. And as I was crossing the border, ah, I was put together with another group of Jews. And I was given then the name Yitzhak. And I liked the name, because Yitzhak means, “he will laugh.”

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Those Who Were There: Voices from the Holocaust,” a podcast that draws on recorded interviews from Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. I’m Eleanor Reissa.

Isaac Zieman grew up in the small Latvian town of Līvāni and was the oldest of four children. Isaac’s father owned a grocery store. He taught Torah on the side, and was a cantor at the synagogue that the family attended. His mother wasn’t a believer, but she kept a traditional home for his father’s sake.

When Isaac was 10 years old he joined a Zionist youth group called Gordonia. He was leading the Līvāni chapter by the time he was 15. Isaac’s parents couldn’t afford to send him to university, so he attended a two-year teacher’s institute instead. When he was 19, he became the head of Gordonia’s Riga branch and devoted himself to Socialist Zionism. But when Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in 1941, Isaac began an odyssey that took him across the Soviet Union twice and across Europe by the time the war had ended.

It is now August 1, 1990, and Isaac Zieman is seated against a black backdrop in a makeshift studio at the Museum of Jewish Heritage’s office in Midtown Manhattan. Isaac has a brown moustache and a goatee that’s mostly silver. His narrow eyes are set off by dark eyebrows and a deeply furrowed forehead. He’s wearing a lavender collared shirt.

Isaac’s interviewers are Toby Blum-Dobkin and Devorah Mann. Toby begins by asking Isaac about Līvāni.

———

Toby Blum-Dobkin: Would you be able to just give us a, a description of your town that, that you were living in, that you’re from, actually?

IZ: Um, it was a small town. And the main street were mostly stores, and nearly all were owned by Jews. There were four synagogues in the town. There were only orthodox synagogues, of course. There were all, um, all colors of Jewish opinion or ideology. There were the orthodox. There were Zionists. There were Labor Zionists. There were orthodox Zionists. There were orthodox anti-Zionists. There were Bundists, and there were Communists. But everybody went to shul, because this was the social place to meet.

Um, and the relationship between the Jews and the Latvians were not close, not socializing, kind of tolerating each other. But there was antisemitism.

The war came to Latvia in ’41 when the Germans attacked the Soviet Union. And, um, ah, one morning, ah, some Communist officials came to our family home. And, uh, they, they wanted to mobilize my father, uh, to, uh—they mobilized people to build obstacles against the advancing German tanks.

And then my mother thought that it would be better if I would go and if the father would stay with the family. So I, I may have been somewhat hurt by that, but I went. And then during the night, when we were working in the, in the forest, we heard bombs falling. And then later in the same night, we were told that we can go home, and, um, I went home. And, um, I knocked and there was no answer. So I assumed that my parents had gone somewhere to hide from the bombing.

So I grabbed a bicycle. And the bombs were falling. And there were other Jews trying to—who were moving. And I went to synagogues and I asked, uh, whether anybody has heard of a family Zieman, and nobody had heard of a family Zieman.

And then I met accidentally a group of Jews that were going toward Russia. So I joined that group. And the Russians put us on trains, and they led us to, uh, Chelyabinsk Oblast, which is, uh, near the Ural, near the Ural Mountains. And, uh, it was a problem to, um, to survive that trip, because we had nothing. Whatever people had in the group, like watches, or jewelry, or whatever, uh, they gave away for food. And that’s how the whole group survived.

And when we came to Chelyabinsk, we were sent to a kolkhoz, a collective farm, called Svobodnyi Trud, which means “free labor,” and we were free laborers. We were laborers that were only given to eat, but not paid anything else. And we were given work to dig ditches, which we did.

And then the winter approached, and we had no winter clothes. So we went and we asked for winter clothes. So we were told by the authorities that there, there was no winter clothes. But, they said, “We can give you permission to go to Central Asia where it’s warm and where does, one does not need winter clothes.”

I suppose they didn’t know what to do with us. They didn’t need, uh, us, to feed us, so they were probably just as happy to get rid of us. So we went all to Central Asia. And on the way, my friend, Leibele Plotkin from Krāslava, he had finished a language institute. And I had finished at teacher’s institute. So he said, “Why do we have to work so very hard? Maybe we could become teachers.”

So when we arrived in Kazakhstan, both of us went to the capital of Kazakhstan, Alma-Ata, and we said that we are teachers. And they said the only kind of teachers they needed was foreign language teachers. We said, “Yes, we could teach German.” And we were both sent to two different schools in Kazakhstan at the other end, at the western end, of Kazakhstan.

I still remember, the trip lasted about a week to get from the capital of Kazakhstan in the east, near Mongolia, to the place near the Caspian Sea where I was assigned to be a teacher.

It was very poor, and everybody spoke a language I didn’t understand. I was very involved with my students and my teaching. I remember one night, you know, I had not believed in God. I had rebelled. At the age of 13, I had, uh, I rebelled against studying Talmud, and I didn’t believe. And this was a big conflict between me and my father.

And I remember one night going out, and I was so lonely, and I started praying. I started talking to God: “God, um, help me that the war should be over, I could be back home.” I was very much longing for peace and for being back with my family and my friends.

And then one evening, I heard a friend of that feldsher talking about Jews, how the Jews are hiding in the back, in the hinterland, while our Russian boys are dying on the frontier. And that, that hurt me very badly and touched me. And so I decided to volunteer to the Red Army.

Devorah Mann: When was it?

IZ: Um, this, uh, must have been in, uh, either the end of ’41 or the beginning of ’42. There was a political commitar—commissar in my company. And he used to use me as an example of what is bad. I was not like the others. I was slow. I was compulsively clean. Like, “Look at this guy who was raised in a capitalist country, and look what a poor soldier he is.”

And then came an order that all people who were born in capitalist countries should be taken out of the army, and should be sent into forced labor battalions. This may have saved my life. So I became a forced laborer in Stalingrad.

In these forced labor battalions, there were also quite a few Jews from Poland, from Romania, and so on. I heard a group of Jews singing Avenu Malkenu and this was sung with so much feeling that I’ll, I’ll never forget it, till I die. This was very moving, how the Jews were singing, uh, “God, our King, have mercy on us, and, and redeem us.” These were probably all people separated from their families.

And then one day we were sent to a small, uh, railway station near Stalingrad, where we had to unload coal from a train. And we were not given any food. The end of the day, I was, I was very hungry. So I went to a collective farm to steal potatoes. And I went to sleep in the field.

When I woke up the next morning, my whole group was gone. And I was all alone there without papers. So I went to Stalingrad, and I was caught by police. And I told them the story of what happened. And then I was put together with a small group of people, and we were traveling about 10 days maybe.

We survived by stealing, uh, melons—watermelons and sugar melons, mostly watermelons—from collective farms and eating them. And then we arrived, and we were in Siberia. And we were told, “It doesn’t matter what you were before. You may have been doctors, you may have been lawyers, engineers. Here, you will all work in the mines.” And we worked in the coal mines.

We had to stay in the mine until the quota of work was done. It didn’t matter how long. And when the work was finished, then we walked from the mine. All my clothes was wet when I got out of the mine. And as I walked, all the clothes froze.

I remember a lot of hunger. The food was very poor—very watery soup, very little bread. That was all.

And then one day, I think accidentally somebody hit me in the, um, hit me in my face, and I was bleeding. And I got to the ambulance. And a Jewish woman, doctor, saw me, uh, and she was amazed how I looked. I had lost a lot of weight. So, I was sent to Kyrgyzia, which is a neighboring country close to Kazakhstan in Central Asia in the south. And I was sent to a, again, to a kolkhoz.

And, um, I remember during this whole time when I was in Siberia, and also in the beginning of my time in Kyrgyzia, I felt that I had lost my humanity. Because before the war, I was very idealistic. I enjoyed literature and music and all kinds of things, and—but, uh, I had become a different person. And I had thought of myself that I had become an animal, because all I was interested in was sleeping and eating. Nothing else interested me.

So I thought I had lost my humanity forever. So it was a wonderful experience to discover after a while in Kyrgyzia, in that village, that my human feelings came back. It’s like resurrection, like, you know, like a new life. I star—I began—I became interested in a book, and I became interested in a girl. That happened in that village in Kyrgyzia after I had gotten lots of food.

One of the things I remember from that period of my life is that I taught a group of workers in the field. I was in the field, because I was weighing the grain. I taught a group of workers a Hebrew song in Kyrgyz. The Hebrew song is “Heveti Shalom Aleichem.”

So this became “Alb Kelgen Salaam Aleikum,” because Kyrgyz had some Arabic words—salaam aleikum. Alb kelgen means heveti—“I brought”—alb kelgen. So we sang together in Kyrgyz, alb kelgen salaam aleikum.

And then I was sent to a military factory in Kuybyshev on the Volga. And I was a forced laborer in a military factory.

Um, at one time, I became depressed, and I went to see a Soviet psychiatrist. And that woman said to me, “You need a goal.” And I thought about it, what could be a goal for me? And then I thought, to leave the Soviet Union. So I figured out the only way I could leave the Soviet Union is if I could become a Pole. I was a Soviet citizen, and as a Soviet citizen, I could never leave the Soviet Union.

So I talked to some Jewish guys from Poland, and I asked them to show me the Polish alphabet. Then I went to the library, and I took out a Polish book and the same book in Russian. And then, when I worked in the factory during the day, I used the time by trying to acquire some Polish vocabulary.

I went to the Soviet police and I said, “I am Zigmund Tovienski and I was going with a group to the Polish army. And I lost—I went to a bathroom on one station, and I lost them. And I have continued with the train, with another train, and I cannot find them.”

So they put me into a jail, and different people have interrogated me in the middle of the night, and they always ask me different questions—where I lived in Poland, and how I got from Poland to Russia, and all kinds of stuff.

So, finally, I had an opportunity to talk to the director of the, of that place, of that jail. He was, again, a Soviet Jew. I was very scared that I would be sent to some camp in the hinterlands of Russia, and I would die from hunger there. So I figured, if I am to die in this war, I would rather die fighting Hitler. So I said to him, “Listen, if I’m supposed to die in this war, please send me to the punishment battalions, to the most dangerous places on the frontier. I would rather die there fighting Hitler than in the hinterland.” So he sent me to the Polish army.

I was about 10 months in the Polish army. During that time, the war ended. And, uh, I was one day assigned to the battalion headquarters, uh, as an orderly. So I had to, like, sweep the floor, and, uh, heat the stove, and so. And while I was doing it, I was humming to myself some Hebrew songs. And the writer of the battalion heard me hum these songs. And he asked me, “Where do I know these songs from?” And I said, “Before the war, I was a member of Gordonia.” So he said, “I am also a Gordonist—and,” he said, “the political commissar of our battalion, Boleslav Shinitza [?], is also a Gordonist.”

And this was already—the war was ended already. And he said, “And we are planning to leave the army and go to Palestine. Would you be interested in doing that, too?” “Of course!” So I agreed. And I shed my military clothes, and I was given civilian clothes, and a new name, Oizar Kirshtein. And as Oizar Kirshtein, I went to Krakow, and in Krakow I participated in a conference of Labor Zionists.

And then came this episode where we passed the border from Poland to Czechoslovakia, which I had mentioned. And I was given the name of a Greek Jew, Yitzchack Yehovi, and I came to Bratislava. And Yisrael Zilber came to me, “Yitzchack, he said, in Budapest there are a lot of Jewish refugees, and they need to be organized and moved toward Palestine. Go to Budapest.” So, okay. So I went to Budapest.

And I did my work. I went to the houses where there were lots of Jewish refugees. And I talked to them, how important it is that we should have a country of our own, and we should all go to Palestine.

I took a group of Jews, and we went over the border to Austria, westward, and we were caught. And we were put into jail. And a chaplain from America liberated us.

And then I was taken—I was asked to be in the central committee of the Labor Zionist Youth Movement, Noar Halutzi Meuchad, in Munich. So I worked there. My job was to visit all the groups in DP camps and in towns in Germany and, uh, help them organize, and, uh, keep up their spirits, and teach them Hebrew songs, and so on and so forth.

And I was in a tremendous conflict at that time. Because, on one hand, I was—I wanted to go to Palestine and be a halutz. On the other hand, I had the opportunity to study, which I always had wanted to do. So I became depressed. And I got into psychoanalysis. And a whole world opened up for me.

In ’45, in my travels in Germany, I met a woman from my hometown, and I recognized her. And she told me she had been in the hometown in Līvāni when all the Jews, practically all the Jews, were killed by the Latvians. And she told me everything that happened. And this was of course a very terrible news to hear.

Later, when I was studying in Munich, I think I met once a young, a Latvian woman who had met my sister Tzila when she was in the ghetto in Riga. And, um, I mean, I’ve been looking, I’ve been trying to find out. I went in Yad Vashem and so on, but, um, there is no, no trace of her. And, uh, no trace of the rest of my family of course. Where was I?

Yeah, okay, I was in analysis. And my analyst, uh, thought that I was very gifted. And he encouraged me to study psychology and psychoanalysis. And, uh, we had a very, um, close group of Jewish students in Munich. There were, um, there were hundreds of Jewish, uh, youth who had survived the Holocaust or had come from the east and studied in Munich.

TB: What was the Jewish, uh—any impressions or, or, uh, statements about the Jewish community in Germany in those years? Uh, your observations?

IZ: Most of the people were thinking of themselves, of being only temporarily in Germany. Although, some people did remain, but very—a small number remained. And some people went to Israel, some to United States, some to Canada, to Australia, to South America, and so on.

I came to America on the very last day of the Refugee Relief Act, which was April 30, ’57. And as I came here, I started looking for a job as a psychotherapist.

Um… My experience of the loss of my family and of the Holocaust, I had kind of shut out for, um, most of the time, until about 10, 15 years ago. And then I, I got more in touch with, with the loss. And, uh, I’ve been in therapy, of course, for many years myself. And, um, I worked on these things. I’ve given several talks also about psychological effects of the Holocaust. Um, I’ve given talks also about Israel’s political dilemma and lessons of the Holocaust.

And my lesson of the Holocaust, my, my two lessons, uh, one, that the Jewish people should have a country of their own. And, two, that we should not fall into the pitfall of hatred and chauvinism, not imitate the Nazis.

One of the things that pains me is to see Jews influenced by Nazism. I believe that, um… I believe that the Nazi ideology of, um, my people is more important than anything else, my people above alles, above everything, uh, is a, uh, is a, uh, very, uh, antagonistic to the traditional Jewish values. And it, it pains me very much to see Jews that are chauvinistic, and to see Jews that don’t care about justice and about humanity, that only care about Jews. To me, that means that these Jewish minds were poisoned by Nazism. That’s how I see it.

And, uh, I see the war, the war between—it’s not only a war, the war was not only about the Jewish, uh, uh, people. It was also a war against the Jewish spirit, against the Jewish values of love and justice and peace. And, uh, I feel that if we want to be good Jews, we have to hold on to our values, to our traditional Jewish values of justice and humanity.

And it also pains me very much that, um, half or so of the Israeli people don’t give a damn about what happens to the Palestinians. I, I see that as un-Jewish, an un-Jewish attitude. To me, to be a real Jew is to be compassionate and to care about justice.

———

ER: After the war, Isaac Zieman devoted much of his life to his work as a therapist. In the 1950s, he worked with Holocaust survivors in a German displaced persons camp on what he called “therapeutic education.” In the ’70s, he began practicing a type of group therapy called Theme-Centered Interaction, and led workshops in the United States, Germany, and Israel. In the 1980s, he began working with leaders of Arab-Jewish dialogue in Israel and was active with Friends of Peace Now and other organizations.

Isaac Zieman was the only member of his immediate family to survive the war. He died in New York City on April 2, 2007. He was survived by his third wife, two children from his second marriage, and five grandchildren.

To end this episode, we’ll share a song that Isaac sang for his interviewers. He learned it from a young Ukrainian woman when they worked together as teachers in Kazakhstan. Isaac never forgot the words, the melody, the translation, or the woman who sang it to him.

———

IZ [singing in Russian]: Kogda prostym i nezhnym vzorom / Laskayesh’ ty menya, moy drug, / Neobychaynym, tsvetnym uzorom / Zemlya i nebo vspykhivayut vdrug. / Veselyy chas i bol’ razluki / Gotov delit’ s toboy vsegda. / Davay pozhmëm drug drugu ruki / I v dal’niy put’ na dolgiye goda.

TB: What’s the meaning of the song?

IZ: We are so close that we don’t need words to say to each other again and again. Let our tenderness, our friendship, be stronger than—be stronger than passion and more than love, something like that.

———

ER: To learn more about Isaac Zieman, please visit the podcast’s companion website at thosewhowerethere.org. The website includes episode notes, a full transcript, and archival photographs. That’s where you can also find our previous episodes and background information on the Fortunoff Video Archive and the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

“Those Who Were There” is a production of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, which is housed at the Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Department in New Haven, Connecticut. This second season is a co-production with the Museum of Jewish Heritage—A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, New York’s contribution to the global responsibility to never forget. The museum is committed to the crucial mission of educating diverse visitors about Jewish life before, during, and after the Holocaust.

This podcast is produced by Nahanni Rous; Eric Marcus; the Fortunoff Archive’s director, Stephen Naron; and Treva Walsh, collections project manager at the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

Thank you to audio engineer Jeff Towne. Thanks, as well, to Christy Bailey-Tomecek, Joana Arruda, Noa Gutow-Ellis, Samantha Shokin, and Inge De Taeye for their assistance. And thank you to Sam Kassow for historical oversight, and to photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael Leclerc, and our social media team, including Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Sara Barber. Ljova Zhurbin composed our theme music.

Special thanks to the Fortunoff family and other donors to the archive for their financial support.

I’m Eleanor Reissa. Thank you for listening.

###