By Dr. Samuel Kassow

Leon Pommers (Pomeraniec) was born on October 12, 1914, in Pruzhany (Pruzana in Polish), which belonged to the Russian Empire at the time and was then part of Poland from 1919 to 1939. Leon had two sisters: an older sister, Bertha, who emigrated to the United States in the 1930s (and eventually helped Leon procure an American visa), and a younger sister, Sabina, who was born in 1926. Their father, Abram, owned a brewery. When Leon was a toddler, his mother, Fania, first noticed her son’s love of music, and she took him to Minsk to study the piano when he was only five years old.

Pruzhany was a midsized town by Eastern European standards. Jews had lived there for centuries and had long made up a solid majority of the population. There is a town record of a Jewish burial society as early as 1450. In 1644 the Polish King Wladyslaw IV issued a charter that promised Jews the right to trade under the protection of the crown. According to the Russian census of 1897, Pruzhany had 5,080 Jews out of a total population of 7,633. The Polish census of 1931 showed 7,626 inhabitants, 4,208 of whom were Jews.

Pruzhany’s Jews basked in the reflected glory of the great rabbis who had lived there, including Rabbi Joel Sirkes (1561-1640), who was also known as the B’’kh, after his classic text Bayit Khadash; and Rabbi David ben Samuel Ha-Levi (1586-1667), or the T’’az, after his Turei Zahav. One of the titans of Jewish religious thought in the 20th century, Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik (1903-1993)—the Rav—was born in Pruzhany.

Like other towns in interwar Poland, the Jewish Pruzhany where Leon spent his youth was a far cry from the stereotypical shtetl of the American Jewish imagination. Major cultural and economic changes were transforming Jewish life. Pruzhany’s Jews exhibited a lot of interest in politics, and Jewish delegates played a major role on the town council. Jewish young people joined youth movements—some Zionist, some in support of the Jewish Socialist Bund—and it was these organizations that nurtured a dynamic youth counterculture based on reading, sports, hiking, and amateur theater. (When Leon was in his 20s he befriended Menachem Begin from nearby Brest-Litovsk. Begin headed the Betar youth movement in Poland and later became prime minister of the State of Israel.)

There were dozens of organizations and associations in Jewish Pruzhany, including all-important credit societies, artisans unions, religious fellowships, and several Jewish schools. There were two Jewish weekly newspapers, one Zionist and one leftist Yiddishist. Pruzhany also boasted an amateur Yiddish theater. In 1932 the students of the Yiddishist CYSHO (Central Yiddish School Organization) published a rich and detailed history of the town, which drew warm praise from many leading Jewish historians and scholars, including Dr. Emanuel Ringelblum, who would later organize the Oyneg Shabes archive in the Warsaw ghetto, and Dr. Max Weinreich, the director of the Vilna-based YIVO (Yiddish Scientific Institute). The chronicle was a remarkable achievement, and reflected the high educational standards of the school and the remarkable teachers who inspired the children.

By Pruzhany’s standards, Leon’s family stood near the top of the socioeconomic scale. Like many middle-class Jewish families in the region, the Pommers household was multilingual: Leon spoke Yiddish with his father, Russian with his mother, and Polish with his sisters. Leon’s parents also encouraged Leon’s ambitions to become an accomplished pianist—another indicator that, even though they lived in a far-off provincial town, they were cosmopolitan and cultured.

But as Leon noted in his testimony, the escalating antisemitism in Poland, which became especially virulent after the death of revered national leader Jozef Pilsudski in 1935, did not spare the Jews of Pruzhany. While the government and the church strongly opposed the anti-Jewish violence that erupted in many towns, they explicitly endorsed an economic boycott of Jewish shops and businesses. Financial troubles began to beset Leon’s family in the 1930s as the fortunes of his father’s brewery declined, in part because of the Great Depression, in part because of the boycott.

The death of Leon’s father in 1938 was a terrible blow. Since his sister Bertha had already immigrated to the United States, Leon was forced to step up and support his mother and younger sister in Pruzhany. Fortunately, thanks to the remarkable success of his musical career, Leon was able to help. In 1936 Leon had moved to Warsaw, where he studied piano with the finest teachers, including Filip Liberman and, at the Warsaw Conservatory, Zofia Buckiewicz.

Despite what Leon described as the stifling antisemitic atmosphere in Warsaw in the late 1930s, Jews were still a major presence in the Polish popular music and entertainment scene. Prewar Warsaw was known for its cabarets, jazz bands, dance halls, record companies, and film studios, and the composers and band leaders who stood out were Jewish; Jerzy Petersburski, Artur Gold, and Henryk Wars were especially prominent. Leon was able to support himself in the big city by playing in Henryk Wars’s orchestra as well as on several recordings made by Poland’s top record company Syrena. He also found a good gig in a Polish theater.

In addition, Leon was doing very well at the conservatory, whose director, the famed Polish composer Eugeniusz Morawski, took him under his wing. In 1938 Leon was selected to represent Poland at the next edition of the prestigious International Chopin Piano Competition, although it never took place because of the war. Morawski also tried to secure a scholarship to allow Leon to study abroad, even going so far as to sound out General Boleslaw Wieniawa Dlugoszowski about the possibility. Dlugoszowski, a well-connected, lovable rogue and champion drinker (who, perhaps because of these qualities, was sent to Rome in the late 1930s as Polish ambassador) was no antisemite himself, but he regretfully told Morawski that because Leon was a Jew, such a scholarship was out of the question.

In 1939 Leon’s life was upended by the German invasion of Poland. Caught in Warsaw by the outbreak of the war, Leon joined the hordes of refugees who plodded east along jammed roads under constant German bombardment. He reached Pruzhany, but after the Soviets attacked Poland from the east and occupied his native town, Leon, like many others, made his way to Vilna. Within a short time, some 15,000 Jewish refugees had crowded into Vilna—mainly because, after a brief Soviet occupation in September and October 1939, Vilna became Vilnius, the capital of neutral Lithuania. The Soviets offered Vilna to the Lithuanians as a present, and the Lithuanians, who had lost the city to a Polish military land grab in 1920, were overjoyed to recover their ancient capital. The present did come with a few strings attached: Lithuania had to grant the USSR the right to have bases and station thousands of troops in the country.

For eight months, however—between the end of October 1939, when the Lithuanians regained Vilnius, and June 16, 1940, when the Soviets suddenly took over the Baltic states—neutral Lithuania was a fragile oasis of stability and calm in a war-torn Europe. Surrounded by Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Russia, Lithuania was a flimsy raft in a raging sea, but for the time being, it was “free.” Jewish political parties, a vigorous Jewish press, and the Yiddish Scientific Institute in Vilnius continued to function. The Lithuanian government tolerated the refugees, especially because the U.S.-based relief organization the Joint Distribution Committee took on the burden of supporting them. Thanks to his musical talents, Leon landed on his feet and was able to support himself.

As months passed, many Jewish refugees allowed themselves to hope that this Lithuanian interlude might last and enable them to shelter in place until the war was over. But many others realized that they were living on borrowed time and began to look for ways to leave what they called the “golden cage.” In theory, with the proper papers, one could leave Vilnius for North America, Latin America, or Palestine. In practice, however, getting those precious papers was very difficult. Sweden would not even issue transit visas, except in exceptional circumstances, and for obvious reasons, going through Nazi-controlled territory was for most Jews a nonstarter. It soon became apparent that the only route out was through the Soviet Union, via the 6,000-mile-long Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok and from there to Japan.

Matters became even more desperate when the Soviets brutally ended Lithuanian independence in June 1940 and began a wave of mass arrests. Now instead of a Soviet transit visa, one needed a Soviet exit visa, and running the gauntlet of consulates and government offices became more complicated than ever. In order to get a Soviet exit visa one needed to produce a Japanese transit visa, a visa for a final destination, and hard currency for a rail ticket to Vladivostok and a Moscow hotel where one would wait for a seat on the train. Applying for a Soviet exit visa also meant presenting oneself to the mercies of the NKVD (the Soviet secret police), which, more often than not, provided the applicant with a free trip to Siberia that lacked the creature comforts of the Trans-Siberian and usually stopped well short of Vladivostok. In short, for most Jews in Vilna, getting out was far easier said than done, and between June 1941 and September 1943, the vast majority of Vilna’s Jewish refugees were wiped out by the Germans and their Lithuanian helpers.

Leon, however, was unwilling to wait things out. His sister Bertha in the U.S. had begun the process of getting him an American visa, but the Polish quota was fixed at a mere 6,200 and there was a waiting list of many years. When the war began, much of that quota went unused, but the American consular staff in Lithuania took particular pride in discouraging visa applicants and making the process as onerous as possible. Leon, it seemed, was out of luck—until one day he heard about the Japanese vice-consul in Kaunas, Chiune Sugihara.

Sugihara had had a long career in the lower ranks of the Japanese diplomatic service and intelligence agencies. He was fluent in Russian and had extensive experience in Manchuria, where he befriended White Russian emigres and Jews and even married a Russian Orthodox woman (they divorced in 1935). In 1939, eager to collect intelligence on German and Soviet troop movements in Eastern Europe, the Japanese sent Sugihara to Lithuania, ostensibly to serve as a vice-consul, but actually to work as a spy.

In Kaunas, Sugihara befriended some Lithuanian Jews who soon pointed out to him that he could save lives by issuing Japanese transit visas. Such visas also required a second visa, for a final destination. By 1940, with most countries unwilling to take refugees, it was Dutch Curaçao that served as a credible “final destination” to enable Sugihara to issue Japanese transit visas. Thanks to Jan Zwartendijk, a Dutch businessman and consul in Lithuania, Sugihara’s visas bore the stamp “Valid for travel to Curaçao.”

All in all, Sugihara and Zwartendijk may have saved as many as 6,000 Jewish lives, though Sugihara’s actions ultimately cost him his career. His postwar life was quite difficult, and he lived in obscurity. In 1984, two years before his death at the age of 86, Yad Vashem recognized him as Righteous Among the Nations.

It was thanks to Sugihara and Zwartendijk that Leon was able to leave Vilna in 1941 and travel to Japan. Like many other “Sugihara Jews,” he boarded a Japanese ship in Vladivostok that took him to the port of Tsuruga. There he was taken in hand by a Jewish relief committee based in Kobe. Leon hoped to get to the United States, but since the State Department put as many obstacles as possible in the path of Jewish refugees, he had no choice but to stay in Japan.

But another unexpected benefactor came to Leon’s aid: Tadeusz Romer, the Polish ambassador to Tokyo, who during the war helped many Polish Jewish refugees. Ordinarily, Jews who were unable to leave for a final destination were rounded up by the Japanese and sent to Shanghai, where most of them survived the war. But Romer had been given some blank visas to British dominions, including Canada, and perhaps charmed by Leon’s musical talent and cultured personality, he offered him one of the precious visas to Canada. Romer’s friendship, as well as the support that Leon received from Eugeniusz Morawski, serve as important reminders that, however much Polish Jews rightfully complained about Polish antisemitism, there were many Poles who treated Jews with respect and humanity.

Now Leon had his Canadian visa—but how to get to Canada from Japan? The only way was through Australia via Shanghai. Romer and HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) provided him with the money he needed to make the trip. Leon arrived in Australia just a few days before Pearl Harbor in December 1941. In February, with the war raging in the Pacific, Leon managed to find a place on a freighter that docked in San Francisco, where the American authorities decided that, even though he had a Canadian visa, he lacked an American visa and therefore had to be shipped back to Australia! Happily, Leon’s sister managed to drum up help, and Leon was escorted, under armed guard, to the Canadian border.

In October 1943, Leon was finally able to enter the United States. After the war ended, he learned that his mother and younger sister had shared the fate of the other Jews of Pruzhany, whom the Nazis deported to Auschwitz and murdered at the end of January 1943. Like so many other survivors, Leon felt terrible guilt for having left Europe while his mother and sister stayed behind. Years later he added their names to Yad Vashem’s Names Database of Holocaust victims.

How Leon managed to retrieve his educational credentials from war-torn Warsaw is a story in itself. He enrolled in Queens College, earned a master’s degree, and served on the college’s music faculty until his retirement in 1985, after which he taught at the Mannes School of Music. Leon won widespread recognition as a pianist and accompanist and was nominated for a Grammy in 1986. He played with Benny Goodman, Nathan Milstein, Yehudi Menuhin, and many others.

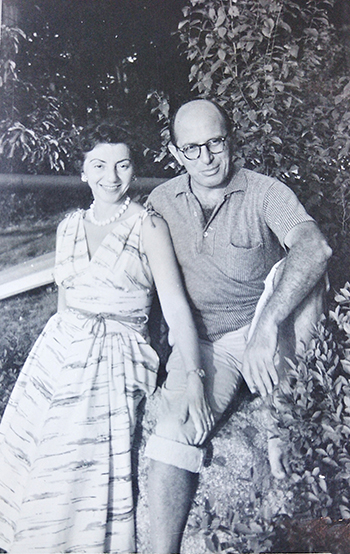

For several years after arriving in the United States, Leon lived with his sister Bertha. In July 1954 he married Warsaw-born Irene Perlman, who had been widowed. Her daughter, Alice Greenwood, became his stepdaughter. They lived in Forest Hills, New York. Those who remember Leon—his stepdaughter and his grandchildren—recall his charm, his refined European manners, and his sense of humor.

Leon Pommers died on June 7, 2001. He was 86 years old.

———

Additional readings and information

Leon’s unedited testimony at the Fortunoff Video Archive (available at access sites worldwide): https://fortunoff.aviaryplatform.com/collections/5/collection_resources/2995.

Holmgren, Beth. “Cabaret Nation: The Jewish Foundations of Kabaret Literacki, 1920–1939.” Polin Studies in Polish Jewry, vol. 31, 2019, p. 273–288.

Levine, Hillel. In Search of Sugihara: The Elusive Japanese Diplomat Who Risked His Life to Rescue 10,000 Jews from the Holocaust. New York: Free Press, 1996.

###

Leon Pommers: My name is Leon Pommers. I live in New York, in Forest Hills. I was born in 1914 in a very small town in Poland. At that time, it was Russia. Pruzana—P-R-U-Z-A-N-A. There were 10,000 inhabitants of which 6,000 were Jews. At an early age, when I was three years old, I touched a piano, and I started to play it. That was for me one of the most ecstatic experiences of my life. And since then I have shown ta—musical talent and I played the piano.

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Those Who Were There: Voices from the Holocaust,” a podcast that draws on recorded interviews from Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. I’m Eleanor Reissa.

From an early age it was clear that Leon Pommers was a gifted musician. When he was just seven, his parents sent him to live with an aunt and uncle in Warsaw so that he could study piano.

Three years later, his aunt and uncle left for Palestine, and Leon returned to Pruzana, where he lived with his parents and two sisters. His father was a successful businessman and together with his four brothers owned a local brewery.

Leon’s career as a concert pianist took off when he was still a young man. He landed a coveted spot at the State Conservatory of Music in Warsaw and performed across the country in concert halls, cafes, and theaters.

In 1938, Leon’s father died. Leon took on the responsibility of supporting his mother and younger sister. By this time, his older sister had married an American and emigrated to New York.

Just one year later, on September 1, 1939, Leon was in Warsaw when the Nazis invaded Poland. He was propelled on a perilous quest to join his sister in America.

It is now more than a half-century later, and Leon is sharing his story with interviewer Toby Blum-Dobkin at a community center in Forest Hills, Queens, in New York City. Leon is dressed in a crisp tan suit, light blue shirt, and patterned maroon tie. He speaks with evident pleasure about some of his wartime adventures despite the gravity of the circumstances in which he found himself.

———

LP: On September 6, a decree was issued by the mayor of Warsaw that all able-bodied men should leave Warsaw and, and go east and regroup there and wait for developments in case of, uh, to form a line of resistance.

And I was one of those who left and went east, and I traveled by foot, by, by car, and by every possible means, and I came to Vilna and immediately contacted the American consulate, but the situation was terribly, terribly bad.

And of course the anxiety about my mother and my sister was terrible. The border between Vilna and the rest of the, of Poland—Poland Poland—was sealed, and we were separated. I was separated from the rest of my family. I even tried to bring them through some, uh, illegal means to cross the border with some guys and so on, but the guys were arrested. My mother came to the border, and she, she was sent back home.

Something unexplainable happened—it was a miracle. One day a rumor was spread, which happened, which happened to be true later, that somebody went—he had some personal contact with the Japanese, uh, consulate in Kovno. Kovno was the capital of Lithuania—Kaunas. He went to see the consul, and he asked him for a Japanese visa. The consul said to him that there is, there isn’t such a thing. There is no immigration visa to Japan. The only thing he can, um, he can suggest is a transit visa.

In order to get the transit visa, he needs a destination visa, but in order to get the destination visa, they have to wait several years. Even more important than the visa was a Russian exit visa. It was an unheard of thing to emigrate from, to leave Soviet Russia. They gave us a very concrete answer. We will let you out, we will give you an exit visa, if you will have a visa to any neighboring country of Russia. Do you understand that the only neighbor—do you know what was the only neighboring country unoccupied by Germany was Japan?

To think in Vilna about Japan, I don’t think—I think to think about Mars now, it’s much easier to visualize Mars than, at that time, to be in Vilna and, and… Even the word Japan so… “But, well, let’s try.” And this man went to Japan—this was how I—he went to Japanese consul. And he said to him, “The only thing I can advise you is to go to a Dutch consul and ask him for a visa to Curaçao, in the, in the Caribbean.” There wasn’t even Dutch consul. There was a, a commercial attaché who had a Philips store. He went to see him, and he asked him for a visa, naively, for a visa to Curaçao.

He says, “What are you talking about? There isn’t such a thing. There are no visas. You can’t even, you will not enter with a visa. You need a permit from the governor. But,” and that was really something incredible, “I’ll give you, I’ll give you, I make a stamp for you and put it on your passport that you, as a Polish citizen, you don’t need a visa to Curaçao.” Of course you don’t need a visa! It’s worthless! And on the strength of this, he receives a perfectly valid, wonderful Japanese transit visa for 10 days, which was a godsent gift.

The next day hundreds, if not thousands, of people—among them I was there, too—in front of the Dutch consulate in Kovno. And I got this coveted stamp—visa—and I went to Japanese consul, and I got my Japanese visa.

And, uh, January 1941 I left Vilna to Moscow. And from Moscow, 12 days and 12 nights through Siberia to Vladivostok. From there, a small boat, Japanese boat. We were, uh, we were there, we were squeezed like sar—like sardines in a box, but deliriously happy.

Toby Blum-Dobkin: Who were your fellow, uh, travelers, fellow passengers?

LP: Refugees. Refugees.

TB: Jewish?

LP: Almost, uh, almost everybody was, yes.

The arrival to Tsuruga: heaven. Flowers, the women dressed in the kimonos, and everything is so beautiful and so fragrant after the bleakness, after the greyness of Soviet Russia. It is, for you, you cannot imagine the, the, the oppression, the, the atmosphere. And to, to leave this behind… You know, the, all of us, after all, almost everybody left someone. We couldn’t—it wasn’t, uh, it wasn’t a leisurely trip.

From there, and that was, you know, on the boat, we were met by the representatives of the Jewish community in Kobe. They were, most of them, Russian Jews from Manchuria who settled in Japan. And they gave us a blanket affidavit. Every Jew who lands in Japan is guaranteed to be supported—because the visa was for 10 days, actually—to be, to be, uh, supported by the Jewish community. And that was acceptable for the Japanese authorities under the condition that they will be, we’ll be all centered in one town for them to have a better control. That was a police state. Only in Kobe we were allowed to live.

But I arrived in Japan in February 1941, 1941, February. And, uh, I was hoping all the time to get my American visa. Each time, something, a delay, each time something new. Each time was postponed. And this postponement and these delays lasted till July.

And I was staying, I was prolonging each time for a couple of months. I succeeded—I answered an ad in a paper given by a Japanese violinist who looked for a pianist to accompany him, to work with him. He was a, an arist—a Japanese aristocrat who was a terrible violinist. He made my, made my life miserable, musically, but he helped me a great deal with prolongation of the visa because he knew the authorities, too. And this way, I, I stayed as long as I could, but, finally, in July, there was a verdict, some kind of an administrative verdict, that we were not allowed to enter the United States anyway, uh, at that time. So I was officially refused in July a visa to the United States, and I was left with nothing.

TB: What, and how long had you been in Tokyo, and what was your—

LP: Seven months.

TB: Could you give me a picture of your life there, the surroundings, maybe contact with, with both other refugees and the local population?

LP: Well, I stayed in Japan seven months, but my whole life, my, my whole life was centered on getting a visa to get out. That was the beginning and end of the day. And I wanted very much to practice. I wanted very much to practice. When I went to the piano the first time, I broke down. I cried.

TB: Where did you find the piano?

LP: A piano, I found the piano in some kind of a, of institution, I don’t remember [inaudible].

Then another interesting thing was that the press attaché of the Polish embassy actually, who took me under his, his, uh, wings, he was himself a newspaperman and a writer. He arranged for me for a radio broadcast in the Tokyo radio. And I played this concert there. Then my fee, which was quite considerable, for me, it was a great… It was in a—I’d never seen it before in Poland—in a beautiful envelope with a beautiful, uh, ribbon. So, you know, all this manifestations of, of aesthetics in Japan were, for me, were something godsent.

But what happens with my visa? One day when I was sitting in the Polish consulate there, the consul tells me, “Let’s go and see the ambassador.” And the ambassador tells him, the consul asked me, “Where would you like to go?” I said, “If I can, for me, it would be the, a godsent country, Canada, because it would be near my sister, and I would be able to proceed with my other plans to go.”

So he went with me to the ambassador’s quarters, and ambassador did something quite unusual. He put his reputation on the line. What he did, he asked for an individual visa from the Canadian government. And I received a godsent gift. You can’t imagine what it meant at that time to have a visa to Canada.

But now we reach another problem. There was no more boat available from, from Japan to Canada, no more commercial contact. To go to the United States, you cannot go. You have no transit visa. The only way from Japan to get to Canada was to go to Australia.

How do you get to Australia? You need a visa to Hong Kong and to the Dutch, to the Dutch East Indies. You cannot get a visa unless you, your trip is paid. Because you are a refugee, nobody wants you. Five hundred dollars from Japan through Shanghai. And, you know, the, the Polish embassy, together with the HIAS—you know, HIAS, the Hebrew—they pay for my trip, to save a musician’s life. They paid 500 dollars.

I landed in Shanghai September 1941. I came to Shanghai with five dollars. It was terribly hot, humid, and I spent four dollars on a white suit, and I walked with one dollar. But you know what, I’m telling you, I was much more carefree than now. It was absolutely impossible to get lost there, you had so many friends, so many groups who arrived before you.

TB: During this period of, uh, go—arriving, uh, to eventually in Tokyo, uh, and Shanghai, did you have any, uh, were you able to have any contact with your family back home? Any kind of communication?

LP: Not, not in—only with my sister in America.

TB: Uh-huh.

LP: There it was impossible, impossible. I was in complete dark. The war was going on, and the anxiety was terrible.

Finally, I left. I left October ’41, which later I found out was the last boat before Pearl Harbor. Because I arrived in Australia the first days of December, a couple of days before Pearl Harbor.

The whole thing is unreal. When I came to Sydney, and I was standing on the, on the deck of the boat, I noticed somebody waving to me from afar on a motorboat. Somebody found out that I was arriving and brought me a contract to appear and to play in a little, in a little theater, which, which our friends, uh, established in, in Sydney. I had a job immediately. It was easier with, with music than, than to be a lawyer.

I stayed there for three months, but there was absolutely no possibility of going to Canada because in the meantime the war broke out.

I got a call from the shipping company that there is a boat, a cargo boat, 9,000 tons, nothing, with 15 passengers on it, which goes from Australia, Sydney, to Vancouver, to Canada. “Would you like to go?” I said, “Yes.”

You know, that was a desperate, uh, move because everything was, uh, mined, and only, uh, out of the five, another friend went with me. No one else wanted to take this chance. And I took the chance. I went on this boat. The boat changed its course every day without letting anyone know because they were all afraid that somebody would find out.

And the captain changed it on, on—he gave the directions in the last moment. All the passengers—that’s important for the story—all the passengers on the boat were mostly British and American citizens. And most of them were diplomats who— that was the only way of going to United States and to England from Australia, uh, by, by this, by this boat. There were only two Polish refugees on this boat, but with perfectly valid Canadian visas. So of course they took us. Took us three weeks to travel. Small boat, you know, like a samovar—9,000 ton, nothing.

We came to, to San Francisco the day when MacArthur landed after this whole, uh, this whole catastrophe in the Philippines. And it came directly from the State Department—from the Defense Department—every available boat in the harbor of San Francisco should load military cargo and run back to Australia with, uh, supplies for MacArthur.

All the passengers left the boat, because they’re British and English and American diplomats. There were only two Polish refugees left in the boat. What do you do with them? We were not allowed to go down, to step down on American soil. We had no visa. Now begins the problem, the legal problem, what to do with us. How do we reach Canada? How to solve it? It was a nightmare.

The immigration officer came on, on board. And I told, I, in my broken English, “What should we do?” He says to me, he says, “You’ll be sent back to Australia.” But I said, “We have only a visa, one-way visa, an exit visa. We cannot go back.”

So we tried B’nai B’rith there. We tried everybody. My sister, I called her up after so many years. The first telephone call to my sister. And, uh, she was trying very hard here. She had some, uh, connections. There was an article here in the paper here: “They will, they will not allowed for the two refugees to sink.”

And the last day, exactly the last day when the boat was ready to go back to Australia, came here directly from the State Department to give us an emergency visa for three days only to cross Ca—uh, from San Francisco to the Canadian border under guard, the two criminals that we were. And the two of us went under guard to the British—to the Canadian border. That was the first time I heard on the border, “Welcome to our country.”

And I came to Vancouver in, uh, February of 1942. I stayed in Canada a year and a half. I was doing very well in Canada, I was, I was playing concerts for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

So from Vancouver, it was, it, it was really smooth sailing already. I received my visa there. Traveled through Toronto, and I crossed to the United States in, uh, Niagara Falls. In a old, dirty train. I hoped I will come, you know, there’ll be a parade for me. I came across the border, and the immigration officer on the train asked me—also disheveled—asked me for my passport and visa. I showed it to him. And he says to me, “Okay, Leon.” I said to him, “What do you mean, ‘Okay’? Make some fuss! Do something! It took me a, almost two years to get it.” Well, I came to New York, and the rest is something, is a different story. Here I am.

The moment I arrived here, I stayed with my sister in the beginning. And of course, the—you, you, you can imagine our meeting, especially with this tragic situation with our, with our family there, it was…

TB: Had you heard anything at that time?

LP: Nothing at all until the end of the war. The first—not until, yes, until the end of the war. The first letter arrived in 1945. My town was liquidated—the ghetto in my town—in the last days of January of ’43 and the first day of February. Our people were taken on, on sleighs 12 kilometers from our town to the railroad station. And then they were sealed in the cars and transported to Auschwitz. And there my mother and my sister perished.

TB: Wh—who—

LP: My sister was 17 years old. This what happened.

I was leading here a life as a professional musician. I was, immediately started to concertize. And then I decided that the life of a traveling artist would be not too pleasant for, uh, in the old, in the later age, and I went back to school. And then I became, uh, I was in, I became a member of the faculty in, and I taught in Queens College from ’68 till I retired for ’85. I was a professor of music there. And then I, when I retired from college, I didn’t want to retire from life. I am teaching now—there is a very good music college called the Mannes College of Music. I teach there.

TB: Thank you. And I would like to, in conclusion, if you have any remarks that, uh, you would like to conclude the interview with, uh, I would be interested in hearing…

LP: Well, my remark, my concluding remarks, is, first of all, I was met with so much, with so much warmth and so much help in this country that I shall be always grateful for every moment of my life here, from beginning to end. I am, I am grateful for every moment I live in this country, and, uh, it—at least it helped me to, it helped me in my renewal. And thank you for asking me to come here.

TB: Thank you very much for coming.

———

ER: Leon Pommers was issued his transit visa by Chiune “Sempo” Sugihara. He was the Japanese diplomat who risked his job and his life to save 5,558 Jews desperate to flee Europe.

When Leon arrived in New York in 1943, he moved in with his sister in the Bronx. He quickly reestablished his career as a concert pianist and composer. Ten years later he was introduced to Irene Perlman, who had also escaped Poland during the war. Irene was a widow with a young daughter named Alice and soon the three were sharing a small house in Forest Hills, where Leon’s piano filled the living room.

Alice Greenwood recalls that her stepfather was like a rock star. “He dressed up in tie and tails,” she said, “and performed at Carnegie Hall and then we went to the Russian Tea Room. At home he never came to the dinner table without a jacket on.”

Nina Hirsch remembers her great-uncle as a joyful man. “He came to the Bronx for my half-birthday,” she said, “with half the cake, half the amount of candles, and got on the piano and played half of a birthday song. He could play ‘Happy Birthday’ about ten thousand ways. As a child it was everything to me.”

Leon Pommers died on June 7, 2001. He was 86.

To learn more about Leon Pommers, please visit our companion website at thosewhowerethere.org. It includes episode notes, a full transcript, and archival photographs. That’s where you can also find our previous episodes and background information on the Fortunoff Video Archive and the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

“Those Who Were There” is a production of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, which is housed at the Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Department in New Haven, Connecticut. This second season is a co-production with the Museum of Jewish Heritage—A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, New York’s contribution to the global responsibility to never forget. The museum is committed to the crucial mission of educating diverse visitors about Jewish life before, during, and after the Holocaust.

This podcast is produced by Nahanni Rous; Eric Marcus; the Fortunoff Archive’s director, Stephen Naron; and Treva Walsh, collections project manager at the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

Thank you to audio engineer Jon Gordon. Thanks, as well, to Christy Bailey-Tomecek, Joana Arruda, Noa Gutow-Ellis, and Inge De Taeye for their assistance. And thank you to Sam Kassow for historical oversight, and to photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael Leclerc, and our social media team, including Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Sara Barber. Ljova Zhurbin composed our theme music. Thank you, as well, to Alice Greenwood and her family for providing archival photographs and background information.

Special thanks to the Fortunoff family and other donors to the archive for their financial support.

I’m Eleanor Reissa. Thank you for listening.

###