By Dr. Samuel Kassow

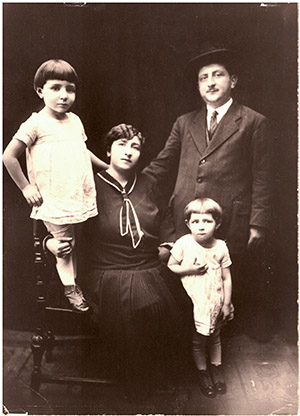

Esther Schwartzman, née Ella Fried, was born in 1929 in Mukachevo, Czechoslovakia, to Zigmond and Leah Fried. She had two older sisters and a younger sister and brother. Her father traded in textiles and dry goods and traveled frequently, but he always returned home before the Jewish Sabbath.

Mukachevo (Munkács in Hungarian, Mukaczovo in Rusyn, Mukaczevo in Ukrainian, and Munkacz in Yiddish) was one of the two major cities (such as they were) of the economically backward, multinational region of Subcarpathian Ruthenia, an area with a complicated and fraught political history. Between 1867 and 1918 the region belonged to the Hungarian part of the Habsburg Empire. In the confused aftermath of World War I, it became the easternmost part of Czechoslovakia, until the Hungarians reclaimed it in 1938 and 1939. Since 1944 Subcarpathian Ruthenia has been part of Ukraine.

Most of the non-Jews in Subcarpathian Ruthenia were Rusyns, a peasant group who spoke a language similar to Ukrainian. As the largely impoverished Rusyns slowly began to develop a national identity, they were torn between three different orientations: they could identify as Russians, as Ukrainians, or as part of a distinct Rusyn nationality. The Rusyns were also divided religiously: some were Uniates, while others were Eastern Orthodox.

Compared to other peoples in Eastern Europe, the Rusyns did not have a history of overt antisemitism. There were no pogroms, interethnic violence was rare, and many Jews remembered decent neighborly relations with the Rusyns. But as various nationalisms, including Rusyn nationalism, began to take hold, points of friction emerged between the Rusyns and the Jews.

As elsewhere in Eastern Europe, Jews gravitated towards the most powerful national group that happened to be in charge, thus earning the resentment of their weaker neighbors. Before 1918, many Jews in Subcarpathian Ruthenia, as well as in Slovakia and Transylvania, embraced Magyar culture, a choice that did not endear them to the Rusyns, Slovaks, and Romanians.

When the area became part of Czechoslovakia, large numbers of Jews educated their children in Czech schools. Rusyns suspected, quite correctly, that their Jewish neighbors, who were mostly Yiddish-speaking, had little interest in Rusyn culture and did not support their national aspirations. In short, by the time of the Holocaust, Rusyn-Jewish relations had cooled considerably, even though the Rusyns remained, for the most part, bystanders rather than perpetrators. But they were bystanders who provided little help as their Jewish neighbors faced deportation.

While the region’s countryside was predominantly Rusyn, its two towns, Mukachevo and Uzhgorod, had large Jewish populations. The 1930 census showed the Jews comprising 44 percent of Mukachevo’s 26,000 inhabitants, and 27 percent of Uzhgorod’s population of 40,000.

The Jewish population of Subcarpathian Ruthenia was remarkable in many ways. The percentage of rural Jews and Jews who eked out a living from agriculture was the highest in Europe. While most of the Jews in interwar Czechoslovakia were economically stable, the Jews in this region suffered from a very high poverty rate.

Another noteworthy feature of the Jewish population in the area was its exceptionally high proportion of religious, Hasidic Jews. The famed “Munkaczer Rebbe” Chaim Eliezer Shapira (1871-1937) was a fierce defender of rigid religious observance, and his long list of targets included not only Zionists but also more moderate religious Jews. Yet, despite the strong religious character of Mukachevo’s Jewry, the modern world was making real inroads during the interwar period. Zionism was gaining supporters, and in the 1920s an important Zionist political figure and educator, Hayim Kugel, settled in Mukachevo, where he established—much to the chagrin of Rabbi Shapira—Czechoslovakia’s only Hebrew language high school. In 1935, he was also elected to the Czechoslovak parliament.

Esther’s childhood experiences and memories reflected the complex nature of Jewish life in her hometown. Her father was a follower of the Munkaczer Rebbe, and the family was very religious, as were all of their family friends. But Esther’s sisters went to Czech schools, while Esther, somewhat surprisingly, attended a Rusyn primary school (she called it a “Russian school” in her testimony). And while most of the region’s Jews were Yiddish speakers, Esther recalled that the language spoken at home was Hungarian—a vestige of the “golden age” of 1867-1914, when the Hungarian nobility courted and protected the Jews and earned not only their gratitude, but also their love of Magyar culture. Esther’s family’s choice of language may also have reflected the fact that, by Mukachevo’s standards, they were solidly middle class rather than lower class.

By the time Esther turned nine, Jewish life in Mukachevo took a definite turn for the worse. Czechoslovakia collapsed, and the city was annexed by Hungary in 1938. Once again under Hungarian rule, the Jews, including Esther’s family, soon discovered that this was a different Hungary from the benevolent Magyar rule they remembered from the old days. Anxious to recover the territories lost after World War I, Hungary allied itself with Nazi Germany and joined its attack on the USSR in 1941.

The Hungarians also began to implement a new series of decrees that limited Jewish economic activity, Jewish access to the free professions, and Jewish admissions to universities. This dealt a serious economic blow to Hungarian Jewry. Esther’s father’s business went downhill. Another shock came when the Hungarian government began to draft Jewish young men for labor battalions in which—unarmed, ill-nourished, and poorly clothed—they followed the Hungarian army into Russia, clearing minefields and digging trenches. These Jewish conscripts suffered an appalling mortality rate.

Yet, despite the fact that the Hungarian government enacted one antisemitic decree after another, it drew the line at allowing the Germans to deport the Jews to the death camps. The landowners and bureaucrats who served under Admiral Miklós Horthy, Hungary’s then regent, had no stomach for such extreme measures. This meant that by early 1944, after most of European Jewry had already been murdered, almost 800,000 Jews in Hungary still lived in their own homes— economically beleaguered but, to all intents and purposes, physically safe. But this safety was more precarious than most Jews realized. The Hungarian army had already carried out massacres of Jews in Ukraine and Yugoslavia, and there were many Hungarian fascists who were chomping at the bit to take power from the conservatives and do Hitler’s bidding by deporting all the Jews to the death camps.

Until March 1944, Esther and her family lived in Mukachevo in tenuous security. Millions of Jews had been killed—many just a few miles away, across the borders with Galicia and Slovakia—but in Mukachevo, Esther’s father eked out a living, the children went to school, and the family continued to observe Jewish holidays. Yes, they had heard about the mass killings in Poland, but such things, they believed, would not happen in Hungary. Admiral Horthy and his friends would never allow it.

In March 1944, Hitler, having learned of Hungarian peace overtures to the West, abruptly summoned Horthy and informed him that Germany would occupy Hungary and install a new, radical right-wing government, led by Döme Sztójay, a rabid fascist and Jew-hater. Horthy remained as regent, but he now toed the new line. Within days, special groups of SS “Jewish experts,” headed by Adolf Eichmann, arrived to plan the deportation of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz. Between May 15 and July 7, almost 450,000 Hungarian Jews were sent to Auschwitz. About two-thirds were immediately sent to the gas chambers.

The destruction of Hungarian Jewry proceeded smoothly and efficiently, mainly because the Germans enjoyed the full and enthusiastic cooperation of the Hungarian government, civil service, gendarmerie, and military. The Catholic church showed some interest in speaking up for Jewish converts but otherwise maintained a deafening silence.

One might well ask, how was it possible for the Germans to deport almost half a million Jews out of Hungary so late in the war? Hadn’t the Hungarian Jews already learned of the Final Solution? Why didn’t more try to escape or hide? After all, the Red Army was by now approaching from the East. But such questions are easy to ask after the fact. For years the Jews in Hungary had been physically safe, and their leaders had assured them that they would remain so, even if Hungary’s government might harass them. The young men who might have organized some form of resistance were scattered in the labor battalions. And the Jews of Mukachevo, as well as those in the rest of Hungary, were surrounded by a wall of hostility and indifference. Even if they knew where they were going, what could they have done? To quote Yehuda Bauer, “They were caught on an island in shark-infested waters, and they had no boat. If the island was flooded, they were doomed.”

The Germans and the Hungarians rounded up the Hungarian Jews from east to west, so Mukachevo was one of the first communities to be deported. In April 1944 the Hungarian authorities established two ghettos in Mukachevo—one for the city’s Jews and the other for Jews from nearby rural areas. For about a month, the Jews in these ghettos faced humiliation and near-starvation, which a hastily established Jewish council tried in vain to alleviate. Jews were forced to sing and dance as they dismantled the Munkaczer Rebbe’s famed yeshiva.

On May 15 Hungarian gendarmes forced all Jews to march five miles to a brick factory under an onslaught of beatings. Once they got to the factory, they were robbed of all they had left and then pushed into boxcars, up to 100 to a car, without any sanitary facilities. Many Jews died along the way and some killed themselves. In her testimony, Esther laconically described the journey as “terrible,” unable to put into words the sheer horror of the experience.

Once Esther and her family arrived at Auschwitz, they faced a “selection”: Esther’s mother, younger sister, and younger brother were immediately sent to the gas chambers, while her father, her two older sisters, and she herself were selected for work. Like many Hungarian Jews who were selected for labor, Esther did not spend much time in Auschwitz, but she suffered the searing humiliations that awaited each new prisoner.

Esther’s experience in Auschwitz and the subsequent labor camp highlight once again how important it was to have a network of close family and friends to help one survive. Esther recalled how her father made his way to a fence near her barrack to tell her to volunteer for any transport leaving the camp, convinced that no matter where the Germans sent you, it was better than staying too close to the crematoriums in Birkenau.

By 1944 the Germans were so desperate for labor that Hitler reversed his previous policy and allowed the SS to import Jewish slave workers into the Reich. Esther and her sisters left Auschwitz on a transport that went first to Stutthof and then to a labor camp at Braunau, where they stayed until January 1945, making munitions. Like other prisoners, Esther used whatever chance she had to sabotage the grenades she was filling with explosives. Camp conditions were dismal, but she survived, thanks to the emotional support of her sisters and the moral support of French prisoners of war.

The major Red Army offensive of January 1945 forced the Germans to hurriedly evacuate every concentration camp and labor camp east of the Oder River, resulting in long death marches of hundreds of thousands of prisoners heading deeper into the Reich. In the final months of the war, as the Reich was collapsing and the Allied armies approached from all directions, up to 250,000 Jewish and non-Jewish prisoners died—killed by SS guards, burned alive in barns and barracks, or left to perish from hunger and disease in now overcrowded camps in the Reich. Esther’s father died in Buchenwald shortly before the end of the war.

No Jews survived the German occupation without luck and well-timed miracles. For Esther and her sisters, one of those miracles came when they succeeded in abandoning the death march they were on without getting shot—the customary punishment for not keeping pace. Esther and her sisters now set out on a long and dangerous trip home, which led them through Warsaw, now a heap of ruins, and Lviv. During the entire journey, they enjoyed the help and friendship of other Jewish survivors. One of Esther’s benefactors was murdered, a stark reminder that liberation brought new dangers, especially for Jews in Poland, where up to 1,500 Jews were killed between 1944 and 1948.

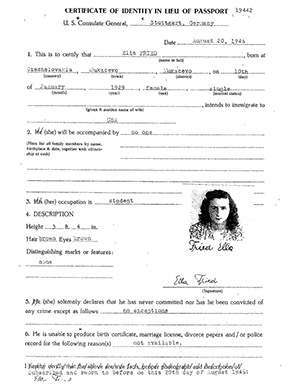

Esther returned to Mukachevo to find little left of what had once been a thriving Jewish community. With the entire region about to become part of the USSR, Esther and her sisters left for Czechoslovakia. From there they made an illegal crossing into the American Zone in Germany. Four of their mother’s sisters lived in the United States and sponsored their immigration in late 1946. On Yom Kippur 1946, just before they sailed, a Jewish chaplain warned them not to talk about their experiences when they arrived in America. People did not want to hear about what they went through, he argued, and they would probably not believe them.

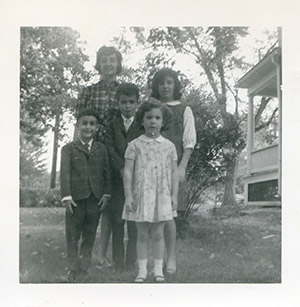

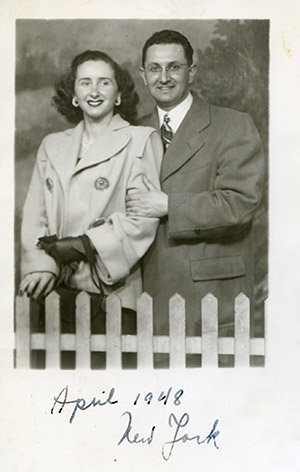

Esther earned a diploma from Washington Irving High School and went to work for a company that made thermometers. In 1948 she married Solomon Schwartzman, who would go on to serve as a rabbi in several small towns across the U.S., including Greenfield, Massachusetts, where they lived from 1959 to 1975—and where Esther was president of Hadassah and the local synagogue sisterhood.

Esther and her husband retired to New Haven, Connecticut, in 1989. They had five children, 13 grandchildren, and 39 great-grandchildren. Esther did not go out of her way to talk about the past with her children, but they knew why they had no grandparents. In Esther’s own words, one can try to bury the past, but “press the right button, and it’s there again.” Yet, despite her pain, she lived a life that was suffused with those same values of Ahavas Yisroel (love of the Jewish people) that had imbued her family and her community back home in Europe.

Esther Schwartzman died on July 26, 2020. She was 91 years old.

———

Additional readings and information

Esther’s unedited testimony at the Fortunoff Video Archive (available at access sites worldwide): https://fortunoff.aviaryplatform.com/collections/5/collection_resources/1790.

Braham, Randolph L. The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary. Condensed ed. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2000.

Segal, Raz. Days of Ruin: The Jews of Munkács During the Holocaust. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem Publications, 2013.

###

Esther Schwartzman: I remember my father coming home very often from the synagogue in the evening services, and he said that more Jews came across the border. They had smuggled. I was, uh, maybe 11, 12 years old, but I remember them telling horrendous stories about, uh, some of the things that the Polish people had gone through and that, how they had walked for days and nights and crossed the border. So, uh, there were people who had put them up and sheltered them.

You know, aside from the fact that it was very hard to believe, I think the people kept thinking that it would only—it’ll go away. It, it happened there, but it’ll—it will certainly not come to us.

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Those Who Were There: Voices from the Holocaust,” a podcast that draws on recorded interviews from Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. I’m Eleanor Reissa.

Esther Schwartzman was born Ella Fried on January 10, 1929, in the city of Mukacevo, Czechoslovakia. When Esther was nine, the city became part of Hungary and was then known as Munkacs [now Mukachevo, Ukraine]. Esther was the third of five children and grew up in a religious family surrounded by grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. Her father was a businessman who dealt in office and school supplies, textiles, and dry goods. Her mother was a housewife.

Esther first attended public schools. But then, with antisemitism on the rise, her parents enrolled her in a private Jewish school for girls.

Hungarian rule brought with it increasing restrictions for Jews. But Esther’s life wasn’t truly upended until early 1944, when the Nazis occupied Hungary and herded the Jews of Munkacs into a ghetto before deporting them to Auschwitz. In all, more than 27,000 Jews from Munkacs and surrounding villages were shipped in cattle cars to almost certain death.

It’s now 46 years later and Esther is sharing her story with interviewer Jaschael Pery at the offices of the Museum of Jewish Heritage. Esther is wearing a lavender silk blouse buttoned at the neck and a string of pearls. Her short, wavy, dark blond hair is combed back from her forehead. From the tears in her eyes and the emotion in her voice, it’s clear that the past is very much present.

———

ES: In a few days, they loaded us up on, uh, the freight cars and cattle cars and transported us to Auschwitz.

We finally got to Auschwitz. There came the separation where they separated us all. They had all the younger women in one area, but, uh, for a while, I was walking, I, I saw my mother was with the two younger children, so I went with her. But, uh, after a little while, uh, along came a German officer, and he said I should go back, “[Unintelligible], you go this way, you go this way.”

And all of a sudden, I was all alone. Um, they, um, told us to go over to a certain area where, um, we entered into a room, and there were hundreds of women, young women. They had us strip completely. [Cries.] And they shaved our heads. [Cries.] I didn’t know what happened to anybody else from my family. I didn’t see anyone for a while. And later I saw my two older sisters, and we, uh, stared at each other, standing there totally, in total undress, and with our hair shaved. But, uh, at least we found each other.

Uh, they consequently gave us dresses. Each one got a different dress. They were not the prisoners’ dresses yet, just a dress they selected and threw it at us. Um, then we were lined up, and they painted this big cross on our backs from top to bottom and across our backs. I suppose so we couldn’t run away so we could be easily identified. And, uh, that is all that we had to our names: a dress.

One day, somebody came in with a message that my father is in, uh, is outside somewhere beyond the fence, and he wanted to see us. And we went to the fence to see him. You couldn’t go too close to the fence because they were electric—electrified, the wire fence, but we talked to him. And he said, “If they ever ask for volunteers to go to work,” he said, “you’ll be the first ones to volunteer.” He said, “I don’t care what work, whatever they ask for, you can do.”

Uh, a few weeks later, uh, they, uh, did ship us out, uh, to another area. They transported us to Bydgoszcz, and there was a camp, Braunau. We were put in these barracks, and they gave us, uh, some decent clothing for the first time. They gave us a towel, actually, and we each had our own bunk bed.

Eventually, they took us to a munitions factory to work, which is where we worked for several months. We filled bombs with, uh, gas, for 12 hours at a time. We worked in these munitions factories and tried, in our own small ways, to sabotage whatever we thought we could do by throwing some debris, or paper, or whatever we thought, you know, in the—inside the grenades or inside the bombs that we were filling. We thought maybe we could do some harm.

Jaschael Pery: So in January ’45, what happened?

ES: In January 1945, we came back from the night shift in the morning, and it seemed like, uh, the talk was going on that they are evacuating the camp. They just lined us up, the entire camp, and, uh, they started us out on a march that morning. And pretty soon we joined up with other camps and as we went on, there were thousands and thousands of prisoners marching on, on this, uh, road.

It was snowing, and the Germans were coming by our side and behind us in the trucks with guns, and they just kept going and yelling for us to keep going and to keep marching and… We marched for days and days, and my older sister said she can’t march anymore, and a couple of times, she said she’s going to stop, she’s not going on. And there were a lot of people who did, and they shot them on the road. She said, “I don’t care if they shoot me, I’m not going anymore.” And at that point, she sat down on the side of the road, and, uh, my other sister and myself, we stayed with her. [Cries.]

I guess the Germans were such, in such a hurry at the time already that they let us stay. After, uh, sitting there for a while, and the columns passed by, and everybody was gone, and we realized that they allowed us to stay without shooting us, we picked ourselves up and started walking in the snow.

There were some farmers who lived, uh, in the vicinity. And, uh, we were afraid to approach them. We had no idea whether they were Germans or whether they would take kindly to us.

So we waited, and when nightfall came, we went into the cellar. There was an open cellar door. There were, uh, several of us together, not just my two sisters. Others came, too, with us. And we hid in this dark cellar, and, fortunately, that farmer was boiling some potatoes for his pigs, and, uh, we took ’em out from the boiling water, and we were so hungry. They were muddy. We took ’em out, and we peeled them, and we ate ’em.

Early in the morning, the farmer came in, and he, uh, he put his, uh, container in to pull out the potatoes to feed his hogs, and he started to swear because there were so few. He couldn’t see us because it was a very dark, big cellar, and we were hidden when we heard him come. He was swearing up and down in German, which we understood of course. But, uh, we didn’t make a sound, and he disappeared.

And during that night was the first time we heard a lot of shooting going on. So we realized what was happening, that the Russians were advancing, and the Germans were retreating. So when we heard the Russian being spoken, we finally emerged from the cellar, and we were able to converse with the Russians, and we asked who they were, and they were Russian soldiers and were freeing Poland. And so we felt we were freed.

The Germans, when they knew that the Russians were advancing, they obviously, uh, ran away. So there were a lot of abandoned farmhouses. We went to the nearest farmhouse, and we occupied it. Uh, we, um, stayed there for a while and found some clothing, some old clothing that they had left behind, which was very, very helpful because we had torn clothing, very little left, and it was cold. So I remember finding underwear, men’s, um—what do they call these?—union suits, warm underwear, and I put on several layers, as did a lot of other people, which was helpful in our travels because it took us weeks before we got home.

We got dressed one day and we decided that, uh, the 17 of us girls who stayed together, we would start out and head home. And, uh, we had to be very careful because the war was still going on, and we heard all sorts of stories from others about the Russians shooting some of the prisoners and some of them taken along, especially the girls.

And, um, as we got to a railroad, we kept inquiring, is there one going towards Warsaw? And they said, uh, in a day there would be a freight train coming through with coal. And that is the way we traveled. We were riding right on top of the coals, or inside cattle cars, or whatever way, as long as they allowed us to go.

We got all the way to Warsaw only to find that Warsaw was a ghost city because everything was completely bombed. There was not one building that was standing in one piece. It was completely bombed, devastated. And there was no Jewish community. We had hoped to get some help from the Jewish community, if there would be one. And, uh, they told us to go to Praga, Polska Praga, they said, which was about seven kilometers from there.

Eventually, we made it to Praga, and there was a Jewish community that, um, tried to help us in a little way, but I guess the war was still on, and they had very little. And, uh, we stayed there for a few days, and, uh, each day, on the streets, there were people selling bread already. And just to see the bread was such a, was such a relief. Just, just to know that we could survive—if, if there’s bread available, somehow we were going to get it, but we had no money.

So what we did is barter with our clothing, and every day they asked me to take off another layer of my underwear so we could sell it in order to buy a loaf of bread, and that’s, that was the most wonderful thing. We had bread. That was all we had, but it was wonderful.

A lot of people did not want to go home. But those of us in our group, we decided we would go back to Munkacs. We had no idea what we would find there, but we knew we had to get back. And after a lot of traveling, it was already beginning of spring. It was March, the end of March. And, uh, you could see the beautiful green scenery already. We were sitting on the freight trains with our legs dangling out and rolling along the hills of the Carpathian Mountains, and eventually arrived back to Munkacs.

I went to see what happened to our home [sighs], which was completely empty of everything. They had taken off the windows, the doors, the kitchen sink. And they ripped open the floorboards to see whether we had hidden any jewelry. And we could see the grass growing already through. I’ll never forget that. The grass was growing in the kitchen under the kitchen floor already.

And, uh, as we were walking along on the street, we met some—somebody. He saw we were Jewish women who had, uh, come back. [Cries.] He asked our names. And this Jewish man said that my uncle survived [cries], who was my father’s younger brother. So we went over to his place. And of course he was overjoyed to see us. And, uh, he took us in. He also, uh, was a survivor. But his young wife and two children were killed. So he was in pretty bad shape himself. He told us that we have another uncle who had, uh, survived and lives in another area.

The city was, um, devoid of Jews, except for a few that came back, straggled back after the war. And I think during that summer maybe, well, there might have been about a hundred Jews who came back. And this was a city where there were 16,000 Jews. And there were some girls and some men who survived. No children and no older people, of course. These were all just young people.

During that summer, we found out that this part of Hungary was going to become, uh, Ukraine. The Russians were going to take it over, and it will belong to the Ukraine. And when we heard that, we realized that unless we get out now, we will not be able to get out.

I can’t remember exactly how and when, but I know eventually we all wound up in the same city, which was called Chomutov, uh, I think north of Prague, which is where we moved to.

And, uh, my mother had four sisters in the United States that had been living here for some time. My sister remembered one of the addresses of one of the aunts. So she wrote a letter to my aunt telling her that we survived and, uh, what happened to the rest of the family.

It so happened that this aunt had moved away from that area. And the mailman who used to deliver the mail to her knew that they no longer lived there. But sensing the importance of a letter from Europe, because he used to for years deliver their mail, and this was right after the war, he felt that this must be important. So after he got through work with his own route, he took that letter and delivered it to them. And that’s the only reason we were able to establish contact with our family in the United States at that time.

So in the spring of 1945—excuse me, ’46—we went and smuggled through the border. We walked—we paid someone, and we walked through the entire night, and, uh, somebody took us from there to a DP camp. During that time in Germany in the DP camps, um, conditions were such that while we lived in barracks, we knew we were free. We knew that the Americans were there. They took us to Bremen. We stayed in Bremen there at, in some camp, waiting for our ship to come in.

When the High Holidays arrived, they had sent a chaplain, a Jewish, uh, rabbi, who performed services for us. And I remember him telling us [cries], “And when we get to America, don’t tell your story.” [Cries.] He said, “Don’t tell anyone what happened because no one will believe you.” But of course when we got to the United States, uh, our family did want to know what happened. And, uh, we described briefly.

Uh, my father was killed in Buchenwald. We found out from a friend later that he was together with him in Buchenwald. And during a bombing raid, he was killed. [Cries.]

I remember when we arrived to the United States, just seeing the Statue of Liberty was wonderful. We arrived also in the middle of the night. And we looked out, and we saw all those bright lights. And, uh, the following morning, they, uh, started to let us get off the ship. And our relatives waited for us all day long there to take us back with them. But it, there were about, um, 1,200 people on that ship. So it took, like, the better part of the day until they, uh, disembarked us all.

And, uh, one cousin finally remained. The rest of them had gone back because the Sabbath was coming, and I guess they had to go home. And she took us back, uh, to another aunt’s house where we would be staying. And to this day I remember all the windows, uh, the store windows with all the glitter, because it was December 20 when we arrived. And we saw the Christmas trees. And I remember all the lights and the windows laden with all these things. And it was, you know, like you get out of a bad dream and you come into fantasy land. That’s what it felt like.

Getting used to the good life in America was not hard. Uh, to be sure, we had our struggles and our ups and downs, uh, when we first arrived, as all newcomers did. But, uh, we were helped. And we had wonderful family here who was very anxious to help us. And I met and married a wonderful man. And we are the parents of, uh, five children and eight wonderful and beautiful grandchildren.

JP: I would like to ask you a question. Raising five children, having grandchildren…

ES: Mm-hmm.

JP: During the raising of the children, being a survivor yourself, your husband a survivor, too, in his way, did you try during the years in some way to tell them? Or did they ask questions about your past?

ES: Of course. Of course they did. Um, let me put it this way. We told them very little in the beginning. It was very hard. I couldn’t bring myself in the beginning to tell them much. But as they got older and they realized they have no grandparents…

Periodically, I would tell them bits and pieces but never all at once too much. But, uh, so as years went on, I thought it would be easier to talk about. But, obviously, it’s not any easier today after, uh, all these years than it was, uh, years ago. Maybe somewhat, but, you know, you bury the past. And, but all you have to do is press the right button, and it’s there again.

JP: Right.

———

ER: Esther Schwartzman died at the age of 91 on July 26, 2020. She had five children, 13 grandchildren, and 39 great-grandchildren in the United States and Israel. Her life as a rebbetzin—the wife of Orthodox Rabbi Solomon Schwartzman—had taken her from New York, Pennsylvania, and Washington State to Vermont, Massachusetts, back to Pennsylvania, and finally, in retirement, to New Haven, Connecticut.

Esther’s eldest daughter, Shelley Bulman, said that her mother was devoted to her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. She kept a list of every birthday and anniversary and had cards and gifts prepared in advance so they would always arrive on time. She never missed a wedding or bar mitzvah, no matter how far she had to travel.

In the last years of her life, Esther volunteered at a local public elementary school with the Jewish Coalition for Literacy, helping young students learn to read. Shelley recalled that her mother took enormous pride in her independence and well into her 80s continued to travel to Israel every year to be with family for Passover. She also traveled back to her home city of Munkacs three times at the urging of her children and grandchildren, who traveled with her.

To learn more about Esther Schwartzman, please visit our companion website at thosewhowerethere.org. It includes episode notes, a full transcript, and archival photographs. That’s where you can also find our previous episodes, as well as background information on the Fortunoff Video Archive and the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

“Those Who Were There” is a production of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, which is housed at the Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Department in New Haven, Connecticut. This second season is a co-production with the Museum of Jewish Heritage—A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, New York’s contribution to the global responsibility to never forget. The museum is committed to the crucial mission of educating diverse visitors about Jewish life before, during, and after the Holocaust.

This podcast is produced by Nahanni Rous; Eric Marcus; the Fortunoff Archive’s director, Stephen Naron; and Treva Walsh, collections project manager at the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

Thank you to audio engineer Jon Gordon. Thanks, as well, to Christy Bailey-Tomecek, Joana Arruda, Noa Gutow-Ellis, and Inge De Taeye for their assistance. And thank you to Sam Kassow for historical oversight, and to photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael Leclerc, and our social media team, including Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Sara Barber. Ljova Zhurbin composed our theme music. Thank you, as well, to Shelley Bulman and her sisters and brothers for providing family photographs and background information about their mother.

Special thanks to the Fortunoff family and other donors to the archive for their financial support.

I’m Eleanor Reissa. Thank you for listening.

###