By Dr. Samuel Kassow

While the world remembers the uprising in the Warsaw ghetto, in fact it was the young people of the Vilna ghetto who first called on Jews to get weapons and prepare to fight. This episode tells the story of the major resistance organization in the Vilna ghetto; its tense relationship with Jacob Gens, the commandant; and its moment of truth on July 16, 1943, when the fighters realized that the Jews in the ghetto saw them not as idealistic fighters but as dangerous young troublemakers.

As we heard in the previous episode, at a clandestine meeting of youth movement members on December 31, 1941, Abba Kovner had called on Jews to prepare for armed resistance. The killings in Lithuania were not a local affair but the first step in a diabolical plan by the Germans to murder all the Jews of Europe. German promises were worthless; if Jews continued to believe them, they would lose not only their lives but their honor as well. But for many, Kovner’s call was a hard sell. Were the Germans really planning to kill all the Jews or was Lithuania a special case? This was a key question. If the killings in Vilna were committed because of specific Lithuanian antisemitism, then it made more sense to flee elsewhere than to fight.

Nisan Resnick recalled that Mordechai Tenenbaum, a leader of Dror, urged his comrades in Vilna to move to the Warsaw and Białystok ghettos. Compared with Vilna, these ghettos seemed safer, and their large numbers of youth movement members offered a wider scope for political and cultural activity. Tenenbaum had befriended an anti-Nazi Austrian sergeant named Anton Schmid, who helped these young Jews. Schmid, who would be arrested and executed a few months later, took Tenenbaum and some of his friends in a truck to Białystok in January 1942. Tenenbaum would lead the resistance movement in the Białystok ghetto and perish in the uprising there in August 1943.

On January 20, 1942, a secret meeting of youth movement activists, Communists, and right-wing Revisionists organized the FPO (Fareynegte Partizaner Organizatsye, or the United Partisan Organization) in the Vilna ghetto. Unlike the Jewish Fighting Organization that fought in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in April 1943, where the combat groups were affiliated with a particular party or youth movement, the FPO consisted of mixed groups, in which fighters from different organizations trained together.

As Arie Distel explained, secrecy was paramount: each group consisted of five members, and only one of them had direct contact with the next echelon. Prewar rivals now worked together: Bundists and Zionists, Communists and Revisionists. Abram Zeleznikov believed that this intraparty cooperation reflected Vilna’s prewar ethos, whereby strong Jewish loyalties often allayed ideological squabbling.

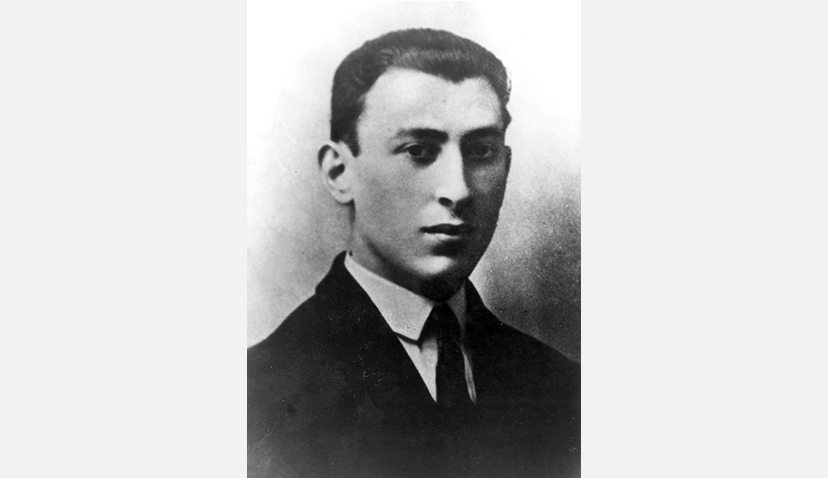

The FPO chose Yitzhak Wittenberg, a Communist, to be its commander. Zenia Malecki recalled that Wittenberg was “our hero.” A shoemaker by trade, Wittenberg was a quiet, serious person who commanded respect. More important, the Soviet Union and the Communist movement were the ghetto’s only long-term hope for salvation, especially because of the hostility of the local units of the Armia Krajowa (Polish Home Army). Therefore, it made sense to choose someone linked to the Communist Party.

Within the FPO, it was the young people, members of the youth movements, who predominated. Abba Kovner, Vitka Kempner, Ruszka Korczak of Hashomer Hatzair; Nisan Resnick of Hanoar Hatzioni; Abrasha Khvoynik of the Bund; and many others. Close bonds that had developed over many years inspired trust and mutual support. Whether Zionist, Bundist, or Communist, these movements imbued their followers with a sense of idealistic commitment and stressed the common good over the selfish needs of the individual. Since most of these young people were unmarried and childless, as Abram Zeleznikov pointed out, they did not have a burden that would have deterred many adults from contemplating armed resistance.

Although at first armed attacks on Germans were hardly an option—the FPO lacked guns—these Jewish young people successfully deployed one key weapon: information. As the Germans did their best to isolate Jews and keep them ignorant of what was happening around them, the youth movements sent couriers to move across Nazi checkpoints and established personal contacts between ghettos.

Most of the couriers were intrepid Jewish girls like Tema Sznajderman and Lonka Kozibrodska, who had an “Aryan” physical appearance, spoke excellent Polish, and possessed a brazen self-assurance. Non-Jewish couriers, like Irena Adamowicz, Poles from the democratic wing of the prewar scout movement, also helped carry information to and from Vilna. In turn, in 1941 and early 1942, these messengers conveyed news of the massacres in Lithuania to the Białystok and the Warsaw ghettos. Information gleaned from the couriers played a key role in the psychological preparation for armed resistance in the Warsaw ghetto and elsewhere.

Against incredible odds, as we learn from Arie Leibke Distel and others in this episode, the FPO managed to smuggle weapons into the ghetto: pistols, grenades, rifles, and even machine guns. Borukh Goldstein worked in a German armory and smuggled in the FPO’s first pistol, in January 1942. Shmerke Kaczerginski, a Yiddish poet who was a member of the FPO and worked in the Paper Brigade (see the notes for the previous episode), got weapons from Lithuanian Communist contacts.

Other members of the Paper Brigade, as Abram Zeleznikov recounts, smuggled in arms and Soviet manuals that showed how to make grenades and repair weapons. Some Jewish policemen were secret agents of the FPO and arranged to be on gate duty when they knew that a Jew would arrive with weapons concealed in a sack of potatoes or under a pile of onions. By the middle of 1943, the FPO, which boasted some 300 fighters organized in two brigades, had amassed a respectable arsenal.

Women played a prominent role in the FPO, and their heroism inspired the other fighters. In June 1942, Vitka Kempner, who would later marry Abba Kovner and become a distinguished psychologist in Israel, carried out the FPO’s first successful attack when she placed a mine under a German train. The young poet Hirsh Glik composed a poem about this exploit, and it soon became a hit song: “Shtil, di nakht iz oysgeshternt” (“Quiet, the Sky Is Full of Stars”). Two young women set out on a mission to infiltrate the German front lines and convey information about the Vilna ghetto and the FPO to the Soviet Union. They were caught by the Germans but escaped and returned to the ghetto. Liza Magun, arrested and tortured to death by the Germans, wrote out a defiant message in her own blood on the walls of her cell. Afterward, when FPO members heard the password “Liza ruft” (“Lisa is calling”), they were to grab their weapons and mobilize.

As it prepared for a final showdown with the Germans, the FPO faced enormous challenges. In a tiny ghetto, how could they maintain secrecy and security? How could they recruit trustworthy people? (Mira Verbin relates how each recruit had to undergo a rigorous interview.) Where could they find and store weapons? Or learn how to shoot? In a ghetto that had only one gate, where each Jew had to undergo thorough and humiliating searches, how could they smuggle guns and grenades past the German and Lithuanian guards or the Jewish police? As if these problems were not enough, the FPO had to wrestle with basic questions about its role and purpose. If its goal was to fight, then how could members persuade the ghetto population to support them when secrecy had made it impossible to even let other Jews know of the organization’s existence and goals?

And then there was the most important question of all: if the FPO was going to fight, where and when should it do so? Common sense dictated that it was insane to fight inside the Vilna ghetto. The ghetto was like a mousetrap, easily isolated and offering no chance of survival. Wasn’t it better for the FPO to leave the ghetto for the forests and join the Soviet partisans? There they could kill more Germans and more likely live to fight another day.

But was it? Morally speaking, could the fighters just leave the ghetto and abandon the Jews to their fate? And what exactly were these young Jews fighting for? As Nisan Resnick reminds us, few members of the FPO believed that they would survive. But as one Jewish resistance leader in Kraków wrote before he died, these young Jews were fighting for “three lines in history.” No, they couldn’t really defeat the Germans or save the Jews in the ghetto. Nor could they save themselves. But the world, and the Jewish people, would remember that they fought back—as Jews. On the other hand, if the FPO fled to the forest and joined the Soviet partisans—and not all Soviet partisans were friendly—would they earn those “three lines in history”? Or would they simply be remembered as bit players in the glorious battle for Stalin and the Soviet state?

Throughout most of 1942, the choice of the ghetto or the forest was more theoretical than real, since no real Soviet partisan movement existed. But by 1943, as Soviet partisan units got organized and sent emissaries into the Vilna ghetto to persuade FPO members to leave for the forest, the organization faced a major dilemma. But it made its decision: stay in the ghetto, fight back when the Germans came to kill the remaining Jews, give as many people as possible a chance to escape, and then—and only then—go to the forests. They knew that this scenario was highly improbable and that they would probably all die in the ghetto. Yet, as Nisan Resnick explained, it was not so easy to escape to the forests and leave their families and the mass of unarmed Jews to their fate.

It had been an article of faith in the FPO that, at the decisive moment, they would get the support of the wider Jewish population. But they made a major miscalculation. The priorities of a father or mother with children were quite different from those of idealistic teenagers in the FPO. If a tailor worked in a shop that had six months’ worth of guaranteed work from the Wehrmacht, Gens’s call to buy time through work made more sense than the chimeric idea of “resistance.” Armed resistance seemed not only suicidal but pointless and irresponsible. Was it worth sacrificing the whole ghetto to kill a couple of Germans? After Stalingrad, after North Africa, maybe—just maybe—Germany might collapse so quickly that the remaining Jews might survive. Or perhaps some German officer might kill Hitler? As long as there was hope, it was important to live, and not to die.

One of the most respected intellectuals of the ghetto, Zelig Kalmanovich, kept a diary in Hebrew, which was retrieved after the war. In this diary, Kalmanovich praised Gens for doing all he could to save the ghetto. At the same time, he lambasted the FPO for its recklessness and irresponsibility. Abba Kovner revered Kalmanovich, who died in the Nazi labor camp of Vaivara in 1944. He was quite hurt when he read the diary but nonetheless had it published in Israel after the war. Indeed, Kovner admitted, had he been 10 years older in the ghetto, he might even have agreed with him.

By April 1943, ominous portents heralded the beginning of the end. Early that month, the Germans announced that 5,000 Jews from surrounding towns, just dumped into the overcrowded Vilna ghetto, would be sent to Kovno, where more Jewish workers were needed. The German officials who organized the transport actually intended for the Jews to go to Kovno, but at some point the security services intervened and vetoed the idea: it was too dangerous, they said; Jews from these towns had been in cahoots with the partisans and constituted a security risk. Gens, convinced that the train was really going to Kovno, offered to accompany the transport. Much to his horror, after a few miles, the train was shunted off to Ponar.

The Germans detached Gens’s car and sent him back to the ghetto. Thousands of Jews jumped off the train, saw where they were, and hurled themselves on their Lithuanian and German guards, wounding many before they were gunned down. Gens, in a separate car, returned to the ghetto. To make matters worse, the next day the Germans told the Jewish police to go to Ponar, help bury the victims, and collect old clothing. They no longer cared whether the ghetto knew the details of Ponar or not. As for Gens, this was a real blow to his prestige. For more than a year he had been telling Jews that if they worked, they might stay alive. But most of those 5,000 Jews murdered in Ponar were young and able to work. If the Germans shot them anyway, it showed that they believed that the liquidation of the Jews was more important than their possible economic value.

But in fact Gens now doubled down on his pleas to the Jews to stay calm and to work. “Kovno-Ponar” made Gens even more fearful of the growing contacts between the FPO and the Soviet partisans, who had been sending emissaries into the ghetto. The disaster, Gens warned, had just gone to show how dangerous it was for Jews to give the Germans any reason to suspect their behavior. In one incident, Gens shot a Jew from the forest who refused to hand over his pistol. He tried to arrest a key FPO commander, Josef Glazman, but was forced to release him when the FPO threatened violence. The commandant tried to reason with the FPO and convince them that they were playing with fire and putting the ghetto in danger.

Gens was trying to play a double game. On the one hand, he sought out the leaders of the FPO, gave them money, turned a blind eye when a few non-Vilna natives left for the forests, and even promised to lead the battle if and when the Germans came to finish off the ghetto. On the other hand, he looked for allies—in the ranks of the underworld and among the leaders of the work brigades—as potential support in case of a final reckoning with the FPO.

That showdown came on July 16, 1943—the “Wittenberg Day” that Jews remembered as one of the most tragic incidents in the history of the ghetto. Yitzhak Wittenberg, the commandant of the FPO, wore a second hat that his non-Communist comrades knew nothing about: as a member of the secret Communist city committee in Vilna. When a Polish Communist arrested by the Gestapo broke under torture and revealed Wittenberg’s name, the Gestapo demanded that Gens arrest him and hand him over. In talking to the Germans, Gens ascertained that the Gestapo wanted Wittenberg because he was a Communist, not because he was in the FPO. Indeed, Gens got the impression that the Germans had no idea the FPO existed.

Many survivors in this podcast have their heartbreaking memories of what happened next. Gens called Wittenberg, accompanied by other FPO members, to a meeting. When Wittenberg showed up, he was surrounded by Jewish police, who grabbed him and led him toward the ghetto gate. But before he got there, armed FPO members jumped the police and freed Wittenberg, who went into hiding. The FPO now mobilized for what it thought was the final battle; to hand over their commander was out of the question.

But then matters took a disastrous turn. Gens spread the word that if the Germans failed to get Wittenberg, they would destroy the ghetto. Should 20,000 Jews die because of one person? Crowds of Jews went through the narrow ghetto streets and hunted the FPO commander. As the FPO realized that the ghetto was against them, they had to decide what to do about Wittenberg. While the commander urged his comrades to fight, some of his fellow Communists told him that he had no choice but to give himself up.

Arie Distel stood outside and held a grenade. Jews were yelling for Wittenberg to come out and give himself up. What should he do? “Your whole way of looking at the world changes in an hour. You had prepared to fight the Germans, attack them when they entered the ghetto, and save as many Jews as possible. But now you’re facing a crowd of Jews who want to attack you?” That was the only way to avoid a fratricidal showdown in the ghetto.

As the ghetto watched in shamed silence, Wittenberg walked through the streets on his way to Gens’s office. The two had a private chat that lasted a few minutes. Gens told Wittenberg that he had had nothing to do with his arrest, that someone outside the ghetto had informed on him. Somehow Wittenberg procured a cyanide capsule. Did Gens give it to him? A fellow member of the FPO? No one knows. But Wittenberg killed himself in his cell. He would give the Germans no information.

The final liquidation of the Vilna ghetto was about to begin.

###

Mira Verbin: One day I got sick with angina. My sister’s husband offered to go to work instead of me. On the way back he was stopped at the gate by the Nazi [Franz] Murer. He was beaten badly in the head, near the ear. They took him to the hospital and there he died.

My sister was very sick after that and refused all help. She completely broke down. His family took care of her. They had a large family and lived in a tiny apartment. She had her own corner. A metal bed with a mattress and a blanket and a desk to eat on. She would sit between the bed and the table and cry.

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Remembering Vilna: The Jerusalem of Lithuania.” I’m Eleanor Reissa. Chapter six: “The Underground.”

In this episode you’ll hear the voices of Nisan Resnick, Arie Liebke Distel, Abram Zeleznikov, Zenia Malecki, and a diary entry by Herman Kruk. We begin with Mira Verbin, whose parents and many extended family members had been killed. Her sister stayed with her deceased husband’s family. Mira was living with strangers.

———

Mira Verbin: One bright day, a Sunday, I went outside to buy something. A young woman I knew from [the youth group] approached me. She was not from Vilna, she was a refugee. She asked to talk privately and told me about the underground that was being organized, the FPO.

Everyone had to have an interview before joining the underground. They accepted only people from youth movements, because they were very concerned about traitors, and they investigated who you were. It was not easy to be accepted. When they asked me, I told them I had nothing to lose.

In the ghetto, we lived 24 hours a day in mortal danger. There was always uncertainty. There were endless actions. Once we got into the underground, we had a goal in life. Revenge, kill, not go to Ponar, as the manifesto said, not go like sheep to the slaughter.

Nisan Resnick: Right away we started to educate people about weaponry. We were able to buy a revolver. The first revolver was hidden in a pipe in the kitchen.

Arie Liebke Distel: The library of the Mefitsei Haskalah was also a storage place—between the books—for some of the weapons—grenades and other things. We gathered there at night and practiced.

Mira Verbin: We learned to take a pistol apart and put it back together, and to shoot. We practiced in basements, but very little, because we tried to save every bullet.

Abram Zeleznikov: How did we get the weapons? You could try and buy weapons on the black market. It was very dangerous and it was very hard to get the money. So the best source of getting weapons was to steal weapons from the Germans.

Arie Liebke Distel: I worked outside the ghetto in an armory. There were large storerooms for Russian equipment that wasn’t up to the Germans’ standards. From time to time I would swipe some bullets. Each time I took from a different storage unit so they wouldn’t notice. They didn’t count them.

Other people in the underground brought in guns in parts, anything they could take apart and hide on their bodies and in their clothes—those special belts for smuggling. There were all kinds of ways. I, I had a long coat, and I put the bullets between the liner and the outer layer, and you couldn’t feel them at all.

I was going on luck—I could have been caught. I had to let people in the underground know in advance that I’d be bringing bullets so that they’d be prepared. They would secure the gate for me. We had people in the underground who also worked in the Jewish police. They would stand by the gate when I arrived and create some chaos—beating someone else—while I snuck through. People suffered for this. I did it maybe once a week, not every day, because it was very dangerous.

Once, I brought Soviet-made hand grenades in a nice package wrapped up like a present, and Liza Magun from the underground came to the gate, and I hugged her as if we were lovers. I passed her the present, and she took it inside.

Abram Zeleznikov: Another way of smuggling in the ghetto was the channels of the sewage, because we had people in the ghetto what have been working in the sanitation in the city beforehand. And we used the sewage of smuggling in things in the ghetto and smuggling out, out things from the ghetto.

Because we have been collecting books and other Jewish materials for the ghetto, we had some transport and between the books we can come over in the city and bring in some weapons. We brought it to Wiwulska and then we risked our lives bringing it in the ghetto. Kruk was smuggling books, and we have been smuggling some weapons. So this is the way we built up a quite good, good arsenal in the, in the ghetto.

Herman Kruk: June 12. Today the Vilna Ghetto was again shaken up. Why? The gate guard in the ghetto detained a fellow with weapons. The detained man opened fire. A Jewish policeman fell, and the ghetto chief, Mr. Gens, shot the shooter, who fell dead. The tragedy of the Jewish masses goes on and has already reached the point that not only are Jews attacked, but Jews attack Jews.

Zenia Malecki: There were police, Jewish, Jewish policemen, which didn’t behave very nicely, unfortunately. They were the privileged ones, and they let it feel as well. Some were bit, I mean, they had probably to put on a show or whatever. They had to show that they are devoted to, to the Germans, that they do what the Germans tell them to do. But it was very painful.

Mira Verbin: The police, including our Jewish police, did not just arrest people. They would beat up the underground people. Not just once or twice. They knew we had weapons. They knew and we denied it. That’s how it was. Just like there were underground people in the police, there were police in the underground, who would cooperate with the Gestapo. It was a very difficult situation.

———

Eleanor Reissa: By this time, the Judenrat, or Jewish Council, had been dissolved, and some of its members murdered. The Jewish police chief, Jacob Gens, was nominally in charge, but as always, the Nazis gave the orders. They periodically told Gens to round up Jews to be killed at Ponar. They threatened him that if he didn’t, they would, and it would be worse. As Gens tried to maintain control, his relationship with the underground grew increasingly strained.

The leaders of the underground were aware of allied advances and partisan activity in the forests outside Vilna. Some hoped they would be liberated. Everyone was playing for time.

They debated their next move. An armed resistance inside the ghetto would have been a suicide mission. The alternative was risking an escape and joining the partisans. But that would mean abandoning the ghetto and any family members who were still alive.

Then, in the summer of 1943, the Nazis arrested a Polish Communist outside the ghetto. Under torture, he betrayed a fellow Communist who was also the leader of the FPO: Yitzhak Wittenberg. The Gestapo demanded his immediate arrest.

———

Mira Verbin: The whole underground, we were all mobilized. I was living with my friends at the center of Strashuna Street, and I was there with 30 people, waiting for orders.

Abram Zeleznikov: I got the order to take out the few pistols that we had, uh, in, in, uh, under the stage in the youth club, and when I went out from the youth club, I was stopped by Jewish policemens, and they asked me where I’m going and what I’m carrying. Of course, I took out my pistol and I was even prepared to shoot. Luckily, there was Abrasha Khvoynik, who was the representative of the Bund in the command of the fighting organization, he told Gens, “You let him go.” So, they let me go and I went to mine post and I gave the pistols. And we have been waiting what is happening.

———

Eleanor Reissa: On the night of July 15, Police Chief Jacob Gens and his deputy, Salek Dessler, summoned the leaders of the underground to a meeting, including Yitzhak Wittenberg. It wasn’t unusual for them to communicate, but this meeting was a setup.

———

Abram Zeleznikov: In the middle of the conversation, Dessler come in with two Lithuanian Gestapo people, and Dessler showed them, “This is Wittenberg.” So they put some irons on Wittenberg and they tried to take him out from the Judenrat through the gate of the ghetto. Of course, the, the fighters of the partisan organization attacked, take up Wittenberg, and ran away in hiding.

Arie Liebke Distel: It happened very fast—seconds. They pushed them aside, grabbed him, and ran away with him. It was late at night and the police were totally taken by surprise.

Abram Zeleznikov: And then come one of the most terrible nights in the Vilna ghetto. Gens called all the Jews, especially, um, especially the strong armed men of the Jewish police. We had a meeting on the, um, square of the Judenrat, where there was a couple of thousands people.

Mira Verbin: Gens collected all of the thugs of the underworld and made a speech that told them that if in a few hours Wittenberg will not be found, the Germans will destroy the ghetto.

Abram Zeleznikov: The Gestapo called Gens and put to him an ultimatum.

Zenia Malecki: Wittenberg has to be delivered. If not, all the 20,000 dwellers will go. The ghetto will be liquidated.

Abram Zeleznikov: Either you bring us Wittenberg alive—and this is very important, because they said “alive”—or we’ll liquidate the ghetto.

And what Gens told them is like this. “You know, as long as we’re productive and we are working, the Germans are letting us live. Now is the question. The Gestapo wants him because he’s a Communist, and if we will not bring him alive, we’ll all be sent to Ponary.”

Well, of course, these people want to live. They haven’t been prepared to sacrifice their life and the life of their families for one person—what was a Communist, and the Gestapo wants him because of not even because he is a Jew, because he is a Communist!

Arie Liebke Distel: Gens sent the tough guys to go find Wittenberg and forcefully bring him in. Plus, he got people from the police to go into every courtyard in the ghetto and explain that if Wittenberg did not turn himself in, the consequences would be dire.

Mira Verbin: When the story of Wittenberg broke out, all the cards were on the table. That’s when the ghetto was incited against the underground. They asked, “Do you think it’s right that because of one man all of us will be killed?”

———

Eleanor Reissa: The crowd in the square turned into a violent mob, running through the streets, shouting, “One or twenty thousand?”

———

Arie Leibke Distel: The ultimatum was that Wittenberg had to turn himself in, and the underground said no. We were all called to our posts— the whole underground was mobilized.

———

Eleanor Reissa: The ghetto was on the brink of civil war.

———

Mira Verbin: The Jewish thugs attacked us with stones and axes in hand. It was horrible—Jews fighting against Jews.

Arie Liebke Distel: I myself guarded the FPO headquarters. I had a grenade in my hand, with the safety clip out. A flood of people came. They didn’t know who we were, what we did, because not everyone knew there was an underground.

Your whole worldview changes in an hour. You had always prepared yourself to fight against the Germans, and to save as many Jews as possible. But suddenly you are standing in front of a crowd of Jews that has come to attack you. And they came to us and demanded, “Where is Wittenberg? Give us Wittenberg!” Wittenberg was in hiding. I didn’t know where he was, because it was highly secret.

Zenia Malecki: He was hidden in my room. I dressed Wittenberg in women’s clothes, and it was bright as can be at 12 o’clock, and I took him to my room. I left him there. They had meetings in the meantime, what to do?

Arie Liebke Distel: We had a dilemma. The command met, minus Wittenberg, and they started to discuss what to do.

Abram Zeleznikov: The fighters understand, if the Gestapo demands the commander of the fighting organization, this means we should start the fight. So, we have been prepared for this. Now from the other side, we have thousands and thousands of Jews what was running over the, the streets of the ghetto, looking, “Where is Wittenberg? Let’s find Wittenberg.”

Nisan Resnick: The Jewish leaders of the ghetto came to convince us that we should give up, that we weren’t on the verge of liquidation, that it was really about Wittenberg. They didn’t convince us. Every few hours, the Germans postponed the ultimatum—three more hours, then four more hours. We didn’t understand the delays, we couldn’t read the meaning in their actions. From one side, they could have come into the ghetto and carried out an action. On the other hand, it was clear that they didn’t want to come in, that they were very cautious about a battle in the ghetto.

———

Eleanor Reissa: After hours of contentious and painful deliberations, the underground deferred to its Communist members to make the decision.

———

Abram Zeleznikov: Sonya Madesker, what was also a member of the city committee of the Communist Party, come from the city and she said that [it was] decided that we couldn’t the start the revolt because the—nobody will help us. It will be a fight against the fighters from the partisan organization with the Jews in the ghetto. And they went to Wittenberg and they told him that he has to go out.

———

Eleanor Reissa: Eventually, Wittenberg was convinced that most of the people in the ghetto would not support an armed resistance. He decided to turn himself in.

———

Nisan Resnick: He said to us, “Look, my comrades have convinced me that the decisive moment hasn’t yet come, and I have to go.” He asked us to take care of his teenage son. He went to Gens, and Gens sent him to the Gestapo.

Zenia Malecki: Gestapo took him and… But next day they found his body, and that was it.

———

Eleanor Reissa: On the morning of September 1, German and Estonian troops entered the ghetto and arrested a battalion of underground fighters—nearly 80 of them were deported to prison camps in Estonia. The underground was decimated, and those remaining agonized over what to do next.

———

Mira Verbin: We argued about whether we should go to the forest or stay with everyone in the ghetto. The headquarters made the decision that there was nothing left to do in the ghetto, so we began sending groups to the forest.

———

Eleanor Reissa: The underground had prepared to fight and then escape through the sewers. Some had even hoped to take the entire population of the ghetto with them.

———

Abram Zeleznikov: It was a fantasy. It was a dream. Because when we had to go down to the sewerage we could go only the fighters, because if we will let in everybody and anybody, we wouldn’t be able to move and to go. And some people want to go with us, who haven’t been fighters in the fighting organization.

Girls—didn’t let them in. And they have hated very much against us and rightly that we, we didn’t take them with us. There wasn’t any, uh, other way. We had only to let in the fighters.

Mira Verbin: My sister refused to go to the forest. I could not convince her, she was too afraid. She told me I could go, but she would not. The Germans were preparing to close the ghetto, and they started sending people to concentration camps in Estonia and Latvia. My sister decided to go there. She said she would manage somehow, she might escape.

When we parted, it was terrible. I went to say goodbye before I left for the forest. It was half an hour before I had to depart. She had a sweater that she knitted by herself, and she gave it to me. I didn’t want to take it, but she insisted on giving it to me as a keepsake. She said: “Go ahead, we’ll meet again. It will be okay. I’ll stay alive.”

Abram Zeleznikov: We went maybe to the channels of the sewerage three or four kilometers. Now it took us eight hours. It went down about 250 people and they go very slowly. If anything happened to somebody before you, you couldn’t move. I had, I had in front of me a girl, she was the secretary of Herman Kruk, Rochelle Mendelson. And she was a big woman and she nearly fainted and I had to—I took her and I carried her on my, my shoulders the last couple of, of hours.

Mira Verbin: We were a group of 28 or 30 people. They told us to leave on Saturday night, because then the Polish, Germans, and Lithuanians would normally get drunk. We went in pairs—one man and one woman. We left through the back entrance of the ghetto; they opened the gate. We walked on the sidewalk, speaking Polish or Lithuanian, and we did not wear our armbands.

Abram Zeleznikov: You had to carry with yourself if you had some weapons. I had only a Colt, this is an American, a big pistol and I had only about four, um, bullets. Only four bullets. That was all what I had. I had two grenades, hand grenades, that was all. Now, what is important that—and they don’t get wet. If they get, get wet, they, they—you couldn’t use them anymore. So, all the time you didn’t look after yourself, you look after your pistol and one of the few grenades.

Mira Verbin: We had to cross through the whole city to get to the Jewish cemetery. We had some weapons, but not enough for everyone. There were more weapons waiting for us at the cemetery. We had to destroy all our documents and certificates because before us, another group had gone to the forest, and they were captured and attacked outside the city. They had documents with them, so the Germans knew who their families were, and they went into the ghetto and took the families out. So, we did not take anything.

Abram Zeleznikov: We come out, we have been wet and exhausted. Luckily, we had support groups. They prepared for us a hiding place when we come out from the sewerage. And after three days, they took us out from the city and we went to the partisans in the forest of Rudniki.

Mira Verbin: We would walk during the nights, and during the days we would hide in bushes or in small forests. At night we would knock on farmers’ doors to ask for food. It was not easy, because, first, everyone knew that the ghetto was being destroyed, so Jews must be wandering in the area. Second, the Germans were everywhere. We walked for a week, only at night. We finally arrived in a partisan area, a cluster of villages under the Red Army’s control. We felt a little freer then.

———

Eleanor Reissa: In this episode you heard from Abram Zeleznikov; Zenia Malecki; Mira Verbin, whose Hebrew testimony is voiced by Rachel Botchan; Nisan Resnick, whose Hebrew testimony is voiced by Claybourne Elder; Arie Liebke Distel, whose Hebrew testimony is voiced by Eddy Portnoy; and a diary entry by Herman Kruk, read by John Cariani.

Next up, chapter seven: “Liquidation.”

This special series about Jewish life in Vilna is written and produced by Nahanni Rous and Eric Marcus. Stephen Naron is the executive producer. Our composer is Ljova Zhurbin. Our theme music is an arrangement of “Vilna, Vilna,” the 1935 song by A. L. Wolfson and Alexander Olshanetsky. The cellist is Clara Lee Rous. Our audio mixer is Anne Pope.

This podcast is a collaboration between the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University and YIVO, the Institute for Jewish Research. I’m Eleanor Reissa. You’ve been listening to “Remembering Vilna: The Jerusalem of Lithuania.”

###