By Dr. Samuel Kassow

The Great Provocation of August 31, 1941, marked another turning point in the tragic history of Vilna Jewry. Until then, the Germans and their Lithuanian helpers had murdered mainly Jewish men. But from now on, women and children were also fair game. The German record keepers at Ponar, meticulous as always, tried to note the precise number of men, women, and children murdered at each mass execution. According to the late Yitzhak Arad, who wrote the standard history of the Vilna ghetto, from the beginning of the occupation to the end of 1941, about 33,000 Jews died in Ponar.

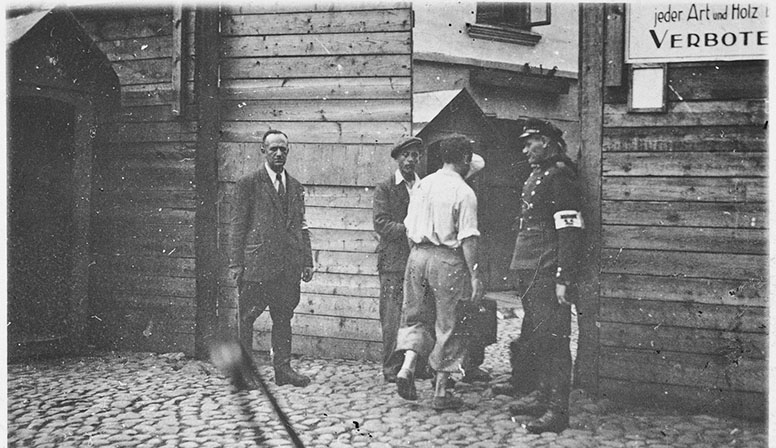

Mass murder and ghettoization went hand in hand. During the first week of September 1941, the Germans planned two ghettos, both in the old Jewish quarter in the center of the city, where mostly poorer Jews lived. Between Sunday night, August 31, and Tuesday, September 2, the Germans prepared for the influx of Jews from the rest of the city by killing the Jews who were already in the area of the planned ghetto. Detailed German records listed 864 men; 2,019 women; and 817 children shot in Ponar on September 2.

While in other cities like Kovno, Kraków, Łodz, and Warsaw, Jews were given a few weeks to get ready for their move into a ghetto, in Vilna Jews had a day at most, often just a few hours. In these other cities, Jews hired carts and wagons to move their things, but in Vilna they could take only what they would carry. As a result, from one day to the next, they had to abandon their family heirlooms, their furniture, and the rest of their hard-earned possessions. There was no time to think. Mira Berger remembered that her family had only about 10 or 15 minutes to pack.

As families frantically prepared large bundles, many too heavy for them to carry all the way to the ghetto, Gentile neighbors stopped by. Some were sympathetic and offered to hide valuables and furniture for safekeeping. Others came to look over the loot that they hoped would soon be theirs. As the pharmacist and political activist Mendel Balberyszski wrestled his hefty pack onto his back, he noticed that the electric kettle that had been tied to its side was missing: just seconds earlier, a Gentile neighbor had filched it. He stormed into her apartment, retrieved the kettle, and set off. Other Jews made one last gesture of defiance. Before the well-known physician Mark Dvorzhetski left his home forever, he grabbed an axe and smashed his piano. Why leave it for the Germans?

From all directions, thousands of Jews converged on the two ghettos. More than 30,000 men, women, and children, all loaded down, many sweating profusely under the several layers of clothing that they had put on, struggled to carry their packs. It was a hot day and rain added to their misery. Often, when people stopped to rest, they lacked the strength to lift their belongings again. Here and there, sympathetic Gentiles stepped up to help. But in other cases, onlookers swooped down and ran off with their packages. Many just gave up and left their bundles by the side of the road.

Fourteen-year-old Yitzhak Rudashevsky wrote in his diary:

The small number of Jews from our courtyard begin to drag the bundles to the gate. Gentiles are standing and taking part in our sorrow. Some Jews hire gentile boys to carry the bundles. A bundle was suddenly stolen from a neighbor. The woman stands in despair among her bundles and . . . weeps and wrings her hands. Suddenly everyone around me begins to weep. Everyone weeps. The people weep looking at the bundles that they can’t carry. . . . I walked laden down, angry. The Lithuanians egged us on, not allowing us to pause. I did not see the streets in front of me. I only felt a terrible fatigue. I felt a storm of indignation and pain burning within me.

Samuel Bak, barely eight years old at the time, recalled the heavy rain and the pillow that his mother made him carry:

And there I saw a, a sort of a caravan of people walking on the road because we’re not permitted to walk in—on the sidewalk. And on the road, near the sidewalk, of course with this enormous rain, it was full of water. And everybody was walking in the water. And they were just walking, you know, like a procession. Everyone carrying something. And I, I had the pillow in my hand. And this pillow became more and more soaked and it started to become so terribly heavy. At a certain point, I threw it away.

That march into the ghetto was yet one more spin on the roulette wheel of life and death. If you lived on certain streets—Mickiewicz or Portowa, for example—you went straight to Łukiszki prison and from there to Ponar. Jews from other, northerly neighborhoods were sent to Ghetto 2 (Glezer, Yidishe, Gaon Streets), while Jews coming from the south were sent to the larger Ghetto 1. But here, too, the Germans toyed with their victims. About 3,000 Jews who were approaching Ghetto 1 from the Novigrod neighborhood to the southwest were shunted into Lidzki Street, and from there to Ponar. But Jews coming from another direction continued straight into the ghetto. Sheila Zwany remembered that “half of our place, half of our house where we used to live, they moved to the ghetto, to the left. Half they moved to the right. This one going to the right were going straight to the jail and from there they shot them. This one going to the left, they went into the ghetto.”

And what about those who reached the ghetto? The very first Jews who entered the ghetto were “lucky.” They quickly took over the empty apartments left by those taken to Ponar over the previous few days. But the half-finished meals on the tables, cups of tea half-drunk, family pictures on the walls, and beds just slept in deepened their feelings of depression and displacement. Samuel Bak remembered:

There were things on the tables. Uh, coffee, which people have not finished to drink, food in the kitchen that was just standing there. Some hungry cats moving around, clothes, clothes on, on the chair near a bed. I mean you could feel that people are still living there. We did not know that these people were already by then dead. We thought that… I don’t know what we thought. I cannot say. We, I was completely disoriented.

Since more than 30,000 Jews had to squeeze into space that could hold only one-fifth of that number, people who arrived a few hours later pushed their way into apartments that were already occupied. Fights broke out. Gangsters—the “tough guys,” as they were called in Vilna—used their fists to grab space. But even as more and more Jews crammed into the ghetto buildings, still more masses of people were forced to sleep in the open, in the narrow streets and courtyards of the two ghettos.

To maintain some semblance of order, Jews in each ghetto formed two new Jewish councils, which quickly got down to work. They allocated housing, set up a rudimentary health system, put plans in motion for schools, and established a Jewish police force, commanded in Ghetto 1 by Jacob Gens, a former officer of the Lithuanian Army, who will figure prominently in the subsequent history of the ghetto. Anatol Fried, one of the few survivors of the first Judenrat slaughtered in early September, headed the council in Ghetto 1, while an ad hoc group of Jewish merchants and artisans formed the council in Ghetto 2.

Some Jews recalled that even in their despair, the first emotion they felt upon entering the ghetto was relief. Now, at least, the Germans and the Lithuanian kidnappers would leave them alone. As Zelig Kalmanovich, a former leader of YIVO, surveyed the crowded lanes packed with people who had nowhere to sleep, he murmured, “Abi tsvishn Yidn.” (At least we’re among our fellow Jews.) His interlocutor, the brilliant Yiddish poet Avrom Sutzkever, penned a poem that began, “Di ershte nakht in geto iz di ershte nakht in keyver. Dernokh gevoynt men zikh shoyn tsu.” (The first night in the ghetto is the first night in the grave. And then you get used to it.) But this fragile optimism did not last.

The grim reality of the ghetto and the German talent for psychological manipulation quickly ended whatever hopes some Jews had that shared suffering might at least lead to communal solidarity and self-sacrifice. Within days, the Germans spread the word that Ghetto 1, centered on Rudnicka Street, was “better” than the smaller Ghetto 2, which was meant to house “unproductive” elements. Jews in Ghetto 2 did all they could to wangle their way into the “productive” ghetto. (Abram Zeleznikov risked his life to move his mother from one ghetto to the other.)

The Judenrat in Ghetto 2 asked for a meeting with their counterpart in the larger ghetto and were shocked to learn that the Judenrat there had already written them off. Believing themselves privileged, they showed little concern for the Jews living just a few blocks away. Or at least that’s how the representatives of Ghetto 2 felt. In his memoirs, Mendel Balberyszski, who attended the meeting as a representative of Ghetto 2, recalled, “We were appalled by what we heard from them.”

In their cynical and brilliant game of divide and conquer, the Germans’ main weapon was the shaynen: pieces of paper that supposedly guaranteed life and survival but more often turned out to be worthless markers on the road to death. As Mira Verbin recalled, “Every time they would announce new and different types of certificates.” One day a white shayn promised safety, and Jews used up their last reserves of gold coins and jewels to buy one. Five days later, however, the announcement would come that the white shayn would expire unless it was stamped “artisan.” So there would be another, panicked rush for these new documents, which in turn would be superseded by the yellow shayn (see below). In the meantime, new classes appeared in the ghetto: those who were lucky enough to land an apartment with reserves of food and valuables and those who were not; those with a shayn and those who lacked one; those with personal connections in the Judenrat and those who were friendless.

But if the Judenrat in Ghetto 1 thought that they were better off, they would soon learn how wrong they were. That September, the Germans continued their roundups in both ghettos, as Ponar claimed more victims. One of the worst days was Yom Kippur. As Jews in Ghetto 2 gathered to pray, squads of Germans and Lithuanians took 1,700 victims to Łukiszki, the way station to Ponar. Jews in the “privileged ghetto” breathed a sigh of relief: they seemed safe. But in the late afternoon, the Germans told the Judenrat in Ghetto 1 to assemble 1,000 Jews at the gate by 7:30 in the evening. Since only a few turned up, the Judenrat ordered the Jewish police to rustle up the requested number.

The police moved through the ghetto and assured Jews with work papers that if they came to the gate, they would simply get their passes stamped and could then go home. But those who believed the Jewish police and showed up at the gate walked into a trap. The Germans marched 2,200 Jews off to their death—including many who held passes. As the historian Yitzhak Arad points out, that Yom Kippur was yet another turning point in the wartime history of the Vilna Jews: for the first time, the Judenrat and the Jewish police took a direct role in handing Jews over, and the ghetto population accused them of collaboration and treachery.

But Yom Kippur was only a prelude to the massacres that reached a crescendo in October. Over the course of that month, the remaining Jews in Ghetto 2 were murdered. In mid-October, the Germans announced that all existing passes would lose their validity. Instead, the Labor Bureau would issue 3,000 yellow passes. Each pass, which had to have a registration number and a special stamp, entitled its holder to include a spouse and two children. In all, 12,000 Jews would gain the right to stay in the ghetto. What awaited the 15,000 Jews without passes was all too clear.

Various Jewish institutions received a limited quota of yellow passes, always fewer than the number of employees. It fell to Jewish directors and managers to play God and to decide who would get a pass and who would not. Dr. Mark Dvorzhetski, who worked in the Jewish hospital, recalled how he waited alongside a longtime colleague and friend, Dr. Kolocner, to learn his fate:

Both of us sat in the corridor of the Judenrat waiting to learn what would happen. Even as we chatted, we knew that a shayn for one of us meant death for the other. . . . I got the shayn, my friend was left to his fate. I was ashamed to look him in the face but I took the document and left. In his place he would have done the same.

Crowds gathered in front of the Judenrat headquarters on Rudnicka 6 and noisily accused the Judenrat members of hoarding the precious yellow passes for their friends and relatives. Meanwhile, lucky holders of the passes registered sisters or even mothers as their wives. Women or men without a pass tried to marry someone who had one. People with three children had to figure out which two children to save or find someone who could put an extra child on their pass. Mira Verbin’s sister quickly married a friend from high school who had a pass. There was no way, however, to save aged parents who were abandoned to their fate.

Those who had no pass had only one option: a malina (hideout). What happened in those hideouts defied description. Mendel Balberyszski remembered that as dozens of terrified Jews cowered in the dark, a mentally disturbed woman suddenly took off her clothes and began to shriek. In other hideouts, people forced mothers to suffocate their children. In one hideout, just as Jews raised a board to let in some breathable air, a passing Lithuanian policeman noticed and took them all away. Yitzhak Rudashevky remembered:

We are like animals surrounded by the hunter. . . . The light of an electric bulb seeps through the cracks. They are pounding and tearing. . . . Suddenly somewhere upstairs a child bursts into tears. We are lost. They stop up the child’s mouth with pillows. The mother of the child is weeping. People shout in wild terror that the child should be strangled. The child is shouting more loudly, the Lithuanians are pounding more strongly against the walls.

Fortunately, that hideout survived, and just in the nick of time Rudashevsky’s mother even secured a yellow pass. On October 24, all holders of yellow passes had to appear at the ghetto gate with their spouses and children for a detailed check. They were then sent to the now-empty Ghetto 2—to allow the Germans and Lithuanians to comb through Ghetto 1. Rudashevsky wrote in his diary:

Grandmother cannot go with us. We are in despair. People can no longer enter the hideout in our courtyard. They have locked themselves in from the inside. . . . We quickly say goodbye to grandmother—forever. We leave her alone in the middle of the street and we run to save ourselves. I shall never forget the two imploring hands and eyes which begged, “Take me along.” We left the ghetto.

The searches for hidden Jews finally petered out in December 1941. By the beginning of 1942, there were about 20,000 Jews in the ghetto: 12,000 who were legal residents—yellow pass holders and their relatives—and about 8,000 who were “illegal” and for whom the Judenrat eventually secured some kind of pass.

During the mass murders, which claimed the lives of about 33,000 Vilna Jews in the second half of 1941, few in the ghetto thought about resistance. People were too busy just trying to find food, a roof over their heads, a pass, a job. Nonetheless, here and there, Jews defied the Germans and the Lithuanians. Sutzkever reported that as the 18-year-old Moshe Frumkin was marching with others to the Łukiszki prison, he suddenly yelled, “Don’t let them take you! Escape into the streets!” Dozens were gunned down, but many, including Frumkin, managed to escape.

One group in the Vilna ghetto that struggled to maintain social cohesion during this traumatic time was the cadre of youth movement leaders, the activists of the HeHalutz (the Pioneer), an umbrella organization that included some key Zionist groupings: Dror, headed by Mordechai Tenenbaum; Hashomer Hatzair, led by Abba Kovner; and Hanoar Hatzioni, led by Nisan Resnick. (Another important youth movement, Betar, would play a key role in the Jewish police as well as in the future underground resistance.)

During the months of roundups and mass murder, activists from these prewar youth movements stuck together and did what they could to survive. In their late teens and early twenties, most of them were unmarried. The bonds of ideological commitment and comradeship, formed over the course of many years, deepened in the face of German persecution as these young people, like other Jews, tried to figure out what to do. Some youth movement leaders established contact with non-Jews who stood ready to help, and this enabled several to elude the roundups. For many weeks, friendly nuns hid Abba Kovner of Hashomer Hatzair in a convent, while Mordechai Tenenbaum of Dror secured fake papers that identified him as a Tatar. He also befriended an Austrian sergeant, Anton Schmid, who would soon help them in many important ways.

As one German roundup followed the next in the last few months of 1941, the leaders of the youth movements in the Vilna ghetto had sharp disagreements over the greater significance of the mass murders in Vilna and in Lithuania. Was this disaster just the beginning of a diabolical German plan to destroy all the Jews of Europe? Or did the killings reflect the specific antisemitism of the Lithuanian population?

By the end of December 1941, 80 percent of Lithuanian Jewry had been annihilated, with only about 40,000 Jews left in the ghettos of Kovno, Vilna, Shavl, and Svientsyan. But elsewhere, most Jewish population centers were untouched. Some leaders, like Mordechai Tenenbaum, argued that the killings in Lithuania were a local phenomenon. What his comrades should do, he urged, was to get out of Vilna and go to other cities, such as Białystok and Warsaw, which seemed “safer.” Using their contacts with the Austrian sergeant, Tenenbaum and his friends eventually left the Vilna ghetto.

But Abba Kovner of Hashomer Hatzair challenged Tenenbaum. Kovner was convinced that Lithuania was just the beginning of the planned annihilation of all European Jewry. Jews had to wake up and realize that all German promises were worthless, that hopes to buy time through labor were illusory, and that the only option was to prepare to fight back.

Kovner and others prepared a proclamation that would be read in Yiddish and Hebrew at a special meeting called for New Year’s Eve 1941. Hopefully, the Germans and Lithuanians would be inebriated enough to leave them alone. This meeting laid the groundwork for the special resistance organization, the United Partisan Organization (FPO), which would form in the Vilna ghetto in 1942. Kovner’s proclamation read in part:

Your children, your wives, and husbands are no more. Ponar is no concentration camp. All were shot dead there. Hitler conspires to kill all the Jews of Europe, and the Jews of Lithuania are just the first victims. Let us not go like sheep to the slaughter. True, we are weak and defenseless. But the only answer to the murderer is: Rise up! Get weapons!

A new year was beginning in the ghetto. Compared with 1941, 1942 would be relatively “quiet.” The Jews of the ghetto settled in, worked for the Germans, and hoped against hope that someway, somehow, they might yet survive the war.

###

Herman Kruk: September 6, 1941. Two o’clock in the afternoon. On Bosaczkowa market people were given five minutes to pack. They drag bundles wrapped in sheets; some just drag the bundles over the stones. Soldiers drive them like cattle. People say that going into the ghetto is like entering a darkness. Thousands stand in line and are driven into a cage. People are driven, people fall down with their sacks, and the screams reach the sky. The mournful trek of being driven out of your home into the ghetto lasts for hours.

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Remembering Vilna: The Jerusalem of Lithuania.” I’m Eleanor Reissa. Chapter four: “The Ghetto.” In this episode, you’ll hear diary entries of Herman Kruk and the voices of Henny Durmashkin Gurko, Mira Berger, Wiera Goldman, Sheila Zwany, Abram Zeleznikov, Mira Verbin, William Begell, and Samuel Bak.

———

Samuel Bak: So I was with my mother in the apartment trying to move as little as possible. And then I remember very well on a very rainy day, the police came, German police and Lithuanian police. And they told us to take a suitcase, something that we could carry, and to go down. And then we had to leave that apartment.

And my mother started to, in a very panicky way, to take things and put in a, in a small suitcase. And then there was not enough place in that suitcase, so she took another one. And she started to, took my hand and we walked the door of the apartment, and then she remembered all of a sudden something, and she ran back and she took a pillow from the bed. So she took the suitcase, me, and the pillow, and went down.

And then, in the courtyard of this big apartment house, there were many of our f— neighbors, that were Jews, standing there. All quite amazed and uncertain of what was going to happen.

It was raining and some were getting soaked and nobody really thought about, uh, opening an umbrella or so, uh… And, uh, when they have brought down all the Jewish, uh, occupants of that apartment house into the courtyard, we were told to go into the street.

And there I saw a, a sort of a caravan of people walking on the road because we’re not permitted to walk in—on the sidewalk. And on the road, near the sidewalk, of course with this enormous rain, it was full of water. And everybody was walking in the water. And they were just walking, you know, like a procession. Everyone carrying something. And I, I had the pillow in my hand. And this pillow became more and more soaked and it started to become so terribly heavy at a certain point, I threw it away.

Henny Durmashkin Gurko: When the ghetto was established, it was a very pathetic, uh, picture of people walking to the ghetto, holding all their bundles, and they could hardly walk. A lot of people couldn’t continue holding their stuff, and they were dropping a lot of packages in the street.

Mira Berger: The ghetto was built in the Jewish, the former Jewish center of the city. There were a few narrow streets, like, two long, narrow streets and connecting short streets. So here they built a wall, a real tall wall. Any house that had a doorway to the outside, to the street, which was not included in the ghetto, they blocked it with, with bricks.

Henny Durmashkin Gurko: They divided the ghetto in two parts. And there was Ghetto Number 1 and Ghetto Number 2.

Samuel Bak: Now, with my mother, with this little suitcase—we arrived to an area which was, uh, once a very heavily populated area of the poorer part of the town w-where, where, where mostly, uh, Jews lived.

What has happened there the day before is that the police has taken out all the people who lived in that area, and all those apartments were empty. And when we came into that part, we were among, I think, maybe the first who came into that part of the, of the city.

Every apartment looked li—as if people went out just five minutes ago. There were things on the tables. Uh, coffee, uh, which people have not finished to drink, uh, food, uh, in the kitchen that was just standing there. Um, some hungry cats, uh, moving around, uh, clothes on, on the chair near a bed. I mean, you could feel that people are still living there.

Wiera Goldman: When we came into the ghetto, some of the houses, it was like… How could you survive seeing that here is still the hot milk and here is still from the baby, the bottle, and here is still the bed where the people went out?

Sheila Zwany: When we came to the ghetto, we were four, four of us and my grandmothers and, and other, you know, family. How we got there a place, um, this aunt and uncle, the children, they took in the middle of the night. So we took their apartment. We went in their apartment. That’s why, you know, we had a place where to stay. We lived in one room, you know, a couple of families because it wasn’t any place. Everybody slept on the floor.

Henny Durmashkin Gurko: When we came to the ghetto, the gate was about to be completed. Everybody was assigned to a different street, and it was a terrible, terrible commotion.

Samuel Bak: I was extremely disoriented and I was shivering because I was completely, I was wet. And we met somebody there, who saw me and he said, but this boy is, uh, is shivering and he needs a coat. And he stood near an apartment which was of his daughter and his grandchildren. And, um, he went into that apartment, he took out a coat. He said, This is of my, uh, grandchild. Take it. And I have put on this coat and I wore this coat for the next four years of a boy, I didn’t know it by then, who wasn’t anymore alive.

Herman Kruk: September 7. The first night in the ghetto. Soaked in my own sweat at about 11:30 at night, I fell back to sleep. The wet cellar didn’t bother me. The hard bundles I was half sitting, half lying on didn’t disturb my sound, drunken sleep. I am not in this world. I am in a cage that was once the entrance from Zawalna to Strashun Street. The streets are flooded full of people and people are being pushed in from the city regularly and incessantly.

Samuel Bak: The streets were full of people. It was pure chaos. We ended up in some room of some apartment. People were arriving and arriving. It became extremely crowded. It was very difficult to breathe there. And, uh, my mother found, um, a corner of a sofa where she has put herself with me close to her.

I even remember something very funny. Because, there was a, uh, Jewish woman with her husband sitting just next to me. And she started all of a sudden to touch her, her purse, the pockets of her coat, and she says, “Oh, my God, I’ve forgotten the keys of the apartment.” People had still normal reflexes.

At a certain point my mother took me and, uh, kept her arm around my head and went out. One of men decided to hang himself.

Henny Durmashkin Gurko: One of my friends lived in the street on Strashuna where I used to come a lot to her also and do the homework with her. Her mother was a widow. And she had two daughters. And they lived in this street. So when they brought us to the ghetto, I thought, naturally, I’ll go to Myra’s house, because I’ll feel comfortable there. I walked up to the apartment, and I’m asking where they are, the Myrans are. Where are they? They’re not there. I’m asking people.

The night before, they took out the whole street of Jews, put them against the wall, and shot them. And she was one of them, the family was one of the people, because they needed room. So this is how they got rid of them. So we lived in this apartment. It was very hard but I ate her preserves, her mother’s preserves that she prepared for the winter. I don’t know how I did it. But we were so hungry.

Mira Berger: We were lucky to come to Ghetto 1, but by the time we arrived, we could only sit down in a hallway. The three of us sat down on our packages in a hallway, and night came and we cuddled, the three of us together in a corner of that hallway.

In the middle of the night, it turned out, the Germans came in and they collected all the people who were in the streets, and they told them, “You are being moved to Ghetto 2. You are here by mistake.” Instead, they took them to Łukiszki and to Ponary and they killed them. By morning, there was much more room. Much more room.

Sam Bak: After a few days, my mother succeeded to get out from the ghetto, I don’t remember for what reason. We went to a relative of ours. This relative was, uh, actually my mother’s aunt, which was kidnapped as a child by a Polish-Russian aristocratic family, baptized and, uh, brought up as their own daughter. This was something that was permitted in the Russia of the czar.

So there she grew up as a child of, uh, of this Polish, uh, Russian, uh, small aristocracy and—but she had always a very strong feeling for her brother, who was my grandfather. And she happened to be in Vilna when the war broke out.

So, um, we came—we went over to her and we asked her what she could do for us, and she said that she will, she will try to hide us. Since she was brought up in a Benedictine monastery, where they had a college for girls, she knew there the sisters of that, uh, monastery. And, uh, the sisters s—agreed to hide us in the closed part of the monastery. And that was, um, a strange coincidence, this monastery was just the building in front of the apartment house where I lived.

And, little by little, my aunt, uh, succeeded to have, h—I mean, my mother’s aunt succeeded to have my mother’s sister, her husband, and also then my father, who meanwhile escaped from the camp, be accepted in the closed part of the monastery. Now we were hiding there.

The nuns gave us a room in relatively comfortable conditions. We had beds, we had th-things to eat. And, um, we had a daily lesson in the Catholic religion.

I suppose my parents were very happy with it because they saw that if on some further occasion, I may be hiding somewhere else, maybe with some Christian people. It is very good that I have a proper education in the Catholic religion. I don’t know if it was for that or if it was just to please the nuns, who felt that they were saving us both ways. Saving us from the Germans and saving us from a wrong religion. I think they thought it will please them. And we spent several months there while some terrible things were going on in the ghetto.

Herman Kruk: Men look for their wives and wives for their husbands, children ask for their parents and parents look for their children. But it becomes clear that many people have not reached the ghetto. Are they just in prison?

Eighty old people have lain for three days and three nights now in a store on Strashun. Nobody takes care of them. They lie on a stone floor and die of hunger.

In a space where 4,000 people used to live there are now 29,000. It is no wonder that thousands of residents fill the streets. The low-ranking German officer Schweinenberg, the real boss of both ghettos, can’t stand it. The scene annoys him, and he orders the streets cleared. Today, he drove into the ghetto at top speed, running over a woman and a child.

Suddenly, the German authorities decided to ease the crowding of the ghetto and took 3,550 persons out, ostensibly transferring them to Ghetto 2. But only 600 persons arrived there. What happened to the 2,950 people? Where are the rest? What’s happening to them now?

Mira Berger: People immediately were taken for to, for work. The able-bodied men were called out of the ghetto and they were put to work in several factories for the Germans. Those people, those lucky ones who got, it was called a shayn. A certificate which permitted them to go out of the ghetto and come back to the ghetto.

Those who didn’t have such a shayn could only offer somebody who did have such a shayn. Listen, I want to sell a pair of shoes. I want to sell this. So this is how trade went on. Those who went out of the ghetto were meeting the Christian population and the trade was going on.

Abram Zeleznikov: I was assigned to work in a group what worked for the Hitler Youth. The work was not very productive. They rather gave us work to carry stones from one place to the other. They beat us very often.

Mira Verbin: They were always announcing new and different types of certificates. A blue certificate and then the next day another color. One day they announced that everyone had to have a yellow certificate, “Shayn for life,” for families of a husband, a wife, and two children. They distributed only some certificates, and there was a rush of theft and chaos to receive one.

I met a school friend of my younger sister’s. He told me he was looking for us and he said, “I have a shayn and I will take your sister as my wife since I have a shayn.” But he told us that, according to the rules of the shayn, he could not live apart from his quote-unquote wife, and his parents did not allow him to have a “wife” without marrying her. My mother said, “Children, do what you want, as long as you stay alive.” So they went to some rabbi and got married, and she moved in with him.

Abram Zeleznikov: When we come in the ghetto, we heard the story about the Judenrats. This was the German system. They come over. They forced the Jews to make a Judenrat. They killed the first people. Under any pretext. Even if, even if the Judenrat was working 100 percent under the orders, they find a pretext to kill them off, because they want to frighten the next ones.

———

Eleanor Reissa: The Nazis had also demanded the creation of a Jewish police force to keep order in the ghetto, and, eventually, to help carry out their aktions. The Judenrat appointed a man named Yacob Gens as head of the Jewish police.

———

Abram Zeleznikov: Gens was a Lithuanian Jew, worked in the beginning of the ’20s, was an officer in the Lithuanian Army. The wife was not Jewish. She was a Lithuanian. No, he didn’t have much to do with Jewishness. He himself considers himself as a Lithuanian.

Herman Kruk: September 18. The Jewish police have a livelihood. If you stand at the gate, you take money for letting people bring in a package. If you walk into the city, you bring bundles that Jews left with Christian friends and you take bribes for this, too. In short, the Jewish police do business. The homes of the Jewish police are full of everything. Bread, butter, fat galore.

William Begell: We worked in that German outfit. It was, uh, L for Luftwaffe, or, um, or air force, uh, 27341. I was working there. I was at that time, in 1941, I was 14 and I was the kitchen boy. I was chopping wood for the field kitchens. I was killing chickens. Uh, I was, uh, helping with the big boilers to make soup and coffee and water, and I learned to speak German very quickly. And, uh, last but not least, I learned to steal.

We had to unload, uh, the food that ranged from, uh, sardines to, uh, marmalade and all the things that were obviously not available in the ghetto, um, to just plain bread. And I have organized the stealing detail, uh, where everybody at the end of the day, uh, would go home with a, uh, a very nice supplement of food.

Mira Berger: We took, like, a pillowcase. If you took the sewing machine and you sewed straight lines, you got channels. And we would sit there during our lunchtime and pour the flour into those channels and we made sure that we could put it on and we tied it around our body.

All of us lost weight, and our coats were big enough to accommodate our body, plus the flour around. And, uh, we were carrying it, those two, two, three kilometers, which we had, and we were coming to the gates.

There were Jewish policemen, which were supposed to, to make sure that nothing is smuggled in. They did not, uh, touch us to find out whether we have flour only. Only if, if German soldiers were, they would touch and try. And a friend of mine, uh, was taken, was caught with some flour and she was taken to Łukiszki and was killed.

Henny Durmashkin Gurko: There was all kinds of aktions going on. An aktion in the ghetto meant that this was a time where you took out Jews and told them all kinds of stories, and actually took them to be killed.

Mira Berger: They would come to the Judenrat and they would say they need thousand Jews. And they wanted the Judenrat to make the selection.

Henny Durmashkin Gurko: You had to be attached to somebody that worked in a special unit. Because there were just so many people that could be attached to one sign, a shayn in Yiddish it’s called—so my brother, uh, had a—had one—got one for me and my mother. My sister went with, uh—with a—uh, with a neighbor.

A group of us, uh, got a job going out of the ghetto. And, uh, we went out. We slept there. We worked through the day. Came the next day, my sister was there. My father was not there. He was taken to Łukiszki.

I became so wild. I came into my mother and said, “Give me all the jewels, everything you got, I’m gonna have to save Daddy.” And I was running to the gates and begging the Nazis to save my father. I gave them—so he says, “Give me this and give me that.” I gave him all, all our valuables. And he said, “Tomorrow I’m bringing him back.” He never came back.

We heard that all the people from Łukiszki were taken to Ponary. And they were shot.

Herman Kruk: September 30. Kol Nidrei. This Yom Kippur eve in the ghetto is unique. In the apartments, people are cooking in big pots as if nothing is the matter. People are washing and scouring as if everything around them is normal. people go to Kol Nidrei service. Kol Nidrei must be over by six-thirty in the evening. The Judenrat ordered this. People recite Kol Nidrei in the dark here. The prayer houses are full to bursting, people stand on the steps, in front of the entrance. The courtyard, the street, everything is bursting—everything is desolate. Jews come to me in the library and ask me to lend them prayerbooks.

Abram Zeleznikov: This was the aktion of Yom Kippur 1941. In the middle of the night, they waked up all the ghetto and said that people what want to get their papers have to go to the entrance of the ghetto and get their papers.

Herman Kruk: October 1. At about nine in the morning the Gestapo came into the ghetto and started snatching people for work. Jews in prayer shawls ran through the streets looking scared. The prayer houses emptied out. Everyone looked for a hole to hide in. At about three in the afternoon the Gestapo demands one thousand Jews. In the ghetto there is an indescribable commotion. The police hunt and chase. The residents hide wherever they can.

Abram Zeleznikov: I tried to hide, and I went up onto the top of the roof of the Judenrat and I tried to get in, in a chimney. And another Jew saw what I am doing and tried to do the same thing, and he was older than me and he was not so quick, and the Lithuanian saw it. He went over and arrested the Jew, had a look in the chimney, saw me, took me out of the chimney. I was all black. He beat me up and I was in blood, and throw me out over the stairs to the courtyard.

Mira Verbin: My mother and uncle, along with 50 people, were hiding in a malina. When we came back from work, we went to check on our mother. They found the hiding place, took everyone out. I was standing like a statue, by the hole, as if my brain was drained. And my sister was screaming: “Mother, where are you?”

Mira Berger: For one day only, they really went from house to house, and whoever they found, whomever they found, they took, and those, those people never, these people never returned. And then they said after this action, there will be no more actions. Those who prefer to, to believe them, believe them. But there was really no choice. You had to believe them because what else could you do?

Henny Durmashkin Gurko: We knew we were endangered, you know, and at, any, any minute of the day, every minute of the day… When we were going out of the ghetto and we were looking around and looking at the Poles, we were wondering, “Why? Why are they free? Why are they allow—” We were kids and, “Why are they allowed to do things and we are not?” And, uh, we saw a world and we were locked in those narrow streets.

Herman Kruk: December 26. It is barely minus eight or ten degrees Celsius [14 to 17 degrees Fahrenheit]. People look at every piece of wood with “pity.” Not a small thing in the ghetto, a piece of wood! No wonder then that the poorer ghetto residents rip wood right off the wall. People rip boards up from the floor, they burn doors with the frames, they cut up stairs from abandoned houses.

———

Eleanor Reissa: By the winter of 1941, every family had members who were missing—especially older people and young children. While some hoped the worst might be over, others suspected that the worst was yet to come.

In the early hours of the new year, a young man named Abba Kovner, a member of the Zionist youth movement Hashomer Hatzair, stood in front of a crowd of young people at a new year’s gathering. He delivered a speech.

———

Abba Kovner: Jewish youth, do not be led astray. Of the 80,000 Jews in the “Jerusalem of Lithuania” only 20,000 have remained. Before our eyes they tore from us our parents, our brothers and sisters.

Where are the hundreds of men who were taken away for work by the Lithuanian “snatchers”? Where are the naked women and children who were taken from us in the night of terror of the provokacija? Where are the Jews [who were taken away on] the Day of Atonement? Where are our brothers from the second ghetto? All those who were taken away from the ghetto never came back. All the roads of the Gestapo lead to Ponary. And Ponary is death!

Doubters! Cast off all illusions. Your children, your husbands, and your wives are no longer alive. Ponary is not a camp—all are shot there. Hitler aims to destroy all the Jews of Europe. The Jews of Lithuania are fated to be the first in line.

Let us not go as sheep to slaughter! It is true that we are weak and defenseless, but resistance is the only reply to the enemy! Brothers! It is better to fall as free fighters than to live by the grace of the murderers. Resist! To the last breath.

———

Eleanor Reissa: In this episode you heard from Samuel Bak, Henny Durmashkin Gurko, Mira Berger, Wiera Goldman, Sheila Zwany, Abram Zeleznikov, William Begell, and Mira Verbin, whose Hebrew testimony is voiced by Rachel Botchan. You also heard diary entries of Herman Kruk, read by John Cariani, and the English translation of Abba Kovner’s speech, originally in Yiddish, read by Arnie Burton.

Next up, chapter five: “Ghetto Life.”

This special series about Jewish life in Vilna is written and produced by Nahanni Rous and Eric Marcus. Stephen Naron is the executive producer. Our composer is Ljova Zhurbin. Our theme music is an arrangement of “Vilna, Vilna,” the 1935 song by A. L. Wolfson and Alexander Olshanetsky. The cellist is Clara Lee Rous. Our audio mixer is Anne Pope.

This podcast is a collaboration between the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University and YIVO, the Institute for Jewish Research. I’m Eleanor Reissa. You’ve been listening to “Remembering Vilna: The Jerusalem of Lithuania.”

###