By Dr. Samuel Kassow

Helen Jonas, née Helena Sternlicht, was 14 years old when the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 put a sudden and brutal end to her idyllic childhood. Only between 2 to 3 percent of the Polish Jews who went through the German occupation survived. Given those terrible odds, their stories of survival are extraordinary, replete with miracles, heart-stopping moments of sheer luck, and a never-ending determination to stay alive. But Helen’s story is especially remarkable in that she narrowly escaped death at the hands of one well-known Nazi—the notorious Amon Göth—and survived thanks to another: Oskar Schindler.

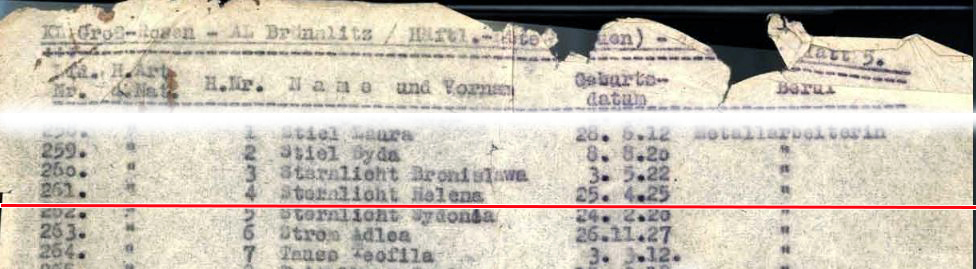

Helen was born in Kraków, Poland, in 1925, the youngest daughter of Szymon and Lola Sternlicht. The family, while not wealthy, was economically secure, thanks to Szymon’s successful ironware business. Lola was a nurturing mother with a keen sense of humor. Helen and her two older sisters, Sydonia and Bronia, grew up in a close-knit Jewish home, with loving parents who observed Jewish traditions and imparted a sense of stability and warmth. Like most Jewish children in Kraków, Helen attended a Polish public school. In the afternoons, she studied in a Beys Yankev school—part of a school system founded by Sarah Schenirer to ensure that Jewish girls from religious homes could also receive a solid Jewish education.

On the eve of the war, there were 57,000 Jews living in Kraków, about a quarter of the total population. Before Poland regained its independence in 1918, liberal Habsburg rule had allowed Kraków and the rest of Galicia a large degree of autonomy; until independence, it was Kraków and Lwów, not Warsaw and Lodz, that had been the beacons of Polish culture with their universities, theaters, and literary scene. The Jews of Kraków built an impressive network of Jewish hospitals, vocational schools, bilingual Polish-Hebrew high schools, and libraries.

Most of Kraków’s Jews spoke Polish, but that did not mean that they were assimilated. They saw themselves as Jews, not as so-called “Poles of the Mosaic Persuasion.” A daily Jewish newspaper in the Polish language, Nowy Dziennik, featured not only current news reports but also articles on Jewish religious thought, Zionism, Yiddish theater, and Hebrew literature. The city’s Jewish adolescents joined youth movements such as Gordonia, Akiba, Hashomer Hatsair, and the Bundist SKIF. (These youth movements would form the backbone of two courageous resistance organizations in the Kraków ghetto. Just before Christmas 1942 they attacked a German officers’ café in the center of town, killing 11 Germans and wounding 13. Very few of these young people survived.)

The Germans started persecuting Kraków’s Jews as soon as they seized the city on September 6, 1939. They burned synagogues, beat Jews on the streets, cut off the beards of religious Jews, and rounded up men and women for forced labor and snow clearing. German soldiers and officials barged into Jewish apartments and stole whatever they wished. Restrictive decrees followed in quick succession: identifying armbands became mandatory, bank accounts were frozen, Jewish businesses were confiscated, and schools were ordered closed. Helen’s father had to hand over his workshop to a German trustee, though he was still able, for a time, to work there. Meanwhile, the family was forced to look on helplessly as Germans made off with their furniture and valuables.

By November 1939 an influx of refugees had increased Kraków’s Jewish population to about 70,000. In the meantime, Kraków had become the capital of the Generalgouvernement, the administrative entity that encompassed Nazi-occupied central Poland. Hitler named Hans Frank as the governor-general, who wasted no time installing himself in regal splendor in the Wawel Castle, not far from the Sternlichts’ prewar home. As thousands of German officials moved into the city, Frank ordered most of the Jews in Kraków to leave. Over the course of 1940, about 50,000 Jews were expelled; only Jews deemed “economically useful,” including Helen’s family, were allowed to stay.

In March 1941 all the remaining Jews—about 16,000—were ordered to move into a ghetto in the city’s rundown Podgorze area, on the southern bank of the Vistula River. They were allowed to bring only 55 pounds worth of belongings per person. Conditions in the ghetto were dismal, with epidemics, food shortages, and severe overcrowding. The Germans surrounded the ghetto with a wall and a fence. They appointed a Judenrat, or Jewish council, that had the thankless task of implementing German orders, even as it made valiant efforts to set up soup kitchens, support orphanages, and even encourage clandestine ghetto schools.

The first two leaders of the Judenrat, Dr. Marek Bieberstein and Dr. Artur Rozenzweig, were respected by the community, but in late 1942 the Germans appointed David Gutter, who was widely remembered as little more than a stooge. Jews in the ghetto especially hated the Jewish police—and its commander, Symcha Spira—for their brutality, their corruption, and their slavish willingness to enforce German orders. Many Jewish policemen were eventually transferred to the Plaszów concentration camp, where they continued to “keep order.”

When Helen and her family first entered the ghetto, she recalled feeling relieved. Perhaps the dragnets and street roundups would now end. Maybe now there might be some stability and quiet. There was even a secret school. Here as elsewhere, however, the Germans showed themselves to be masters of psychological manipulation. They devised a fiendishly complicated system of ID cards and work certificates to set Jews against each other and give them a false sense of security. These pieces of paper decided life and death. On one day a certain work document, which might have been purchased for an enormous bribe, offered a guarantee of survival, but the next day, the Germans might change the rules and decree that only documents in a different color blue, or with a new stamp, would be valid. They applied this system cunningly and brutally in the Kraków ghetto.

One of the system’s victims was Helen’s father, Szymon. He went to the Belzec extermination camp convinced that the Germans were sending him to a new labor camp. After all, why would they want to kill skilled workers? Deportations to Belzec began in May-June of 1942, when 5,000 Jews, including Szymon, were sent off to the gas chambers. Further deportations to Belzec began on October 27, 1942, when 7,000 Jews were killed.

The final liquidation of the Kraków ghetto took place on March 14, 1943. The Germans shot about 700 Jews on the spot, sent 2,300 to Auschwitz, and the rest—including Helen, her mother, and her sisters—ended up at the nearby labor camp at Plaszów, a suburb of Kraków. Shortly after Helen got to Plaszów, the camp’s commandant, Amon Göth, ordered her to work in his quarters as a cleaning woman. For more than a year, Helen and another maid, Helen Hirsch, were in constant contact with one of the worst sadists of the Holocaust. Göth grew up in a wealthy Catholic family in Vienna, where the Göths had a profitable publishing business. In 1931, he joined the then illegal Austrian Nazi Party and worked his way up through the ranks of the SS. In 1942 he served under Odilo Globocnik in Operation Reinhardt, which sent close to two million Jews to the death camps of Sobibor, Treblinka, and Belzec.

In March 1943 Göth became commandant of the Plaszów camp. Established in November 1942, Plaszów was an especially cruel labor camp where many executions also took place. Administratively, it did not become part of the SS concentration camp system until early 1944. It received Jews not only from the Kraków ghetto but also from other Galician towns, Hungary, and other camps evacuated ahead of the advancing Russians in 1944. Plaszów also housed non-Jewish prisoners, and, for a time, many children, until Göth sent them all to Auschwitz in May 1944. All in all, between 30,000 and 50,000 prisoners passed through Plaszów. Between 5,000 and 8,000 died there (the actual camp records were destroyed), though most of the camp’s Jewish prisoners died in the death marches in the last months of the Reich.

Witnesses estimate that during the time that he was at Plaszów, Göth personally murdered at least 500 people. He once confessed that he didn’t feel good about the day unless he’d killed at least one Jew. He stood on the balcony of his villa with a sniper rifle and picked off inmates at random. He once shot a cook because the soup was too hot. Another time he interrupted dictation to shoot two prisoners and then casually continued where he’d left off. Göth also trained two dogs to maul prisoners when he gave a certain whistle.

Göth often beat Helen. Once when he was dissatisfied with how she’d ironed a shirt, he hit her so hard that she suffered permanent damage to her hearing. Helen was convinced that Göth would eventually murder her. But, miraculously, he did not. And on September 13, 1944, the Gestapo arrested Göth on charges of corruption.

What made Helen’s survival even more miraculous was that she was able to hide the fact that her then boyfriend was Adam Sztaub, a leader of an underground resistance group in the camp. Sztaub asked her to rummage through Göth’s office for blank ID forms and papers, which she did at great risk. Göth shot Sztaub after a Ukrainian guard betrayed him and strung up his lifeless body as a warning to others. Sztaub was tortured before his death, but he did not divulge Helen’s name.

Göth lived well and gave many parties, where Helen had to wait on the guests. While his wife Anni and two children stayed home in Vienna, Göth enjoyed an affair at Plaszów with Ruth Kalder, who bore him a daughter, Monika. Kalder, who adored Göth and staunchly defended his reputation, later committed suicide after reading the transcript of his 1946 war crimes trial in Poland.

One of Göth’s frequent guests was Oskar Schindler, a German businessman who had gotten rich after he bought a Jewish enamelware factory in Kraków and secured lucrative contracts with the Wehrmacht, the German armed forces. Schindler’s story is well known. He was no saint. Before the war, he had worked for German intelligence, and in the early years of the occupation, he was a crass opportunist who enjoyed the profits he made from the Emalia factory and engaged in wild parties where he happily cavorted with Gestapo and SS. But then something happened. The mass murder of the Jews affected him and he decided that he would rescue as many as he could. Ultimately, the famous “Schindler’s List” would save about 1,200 Jews.

Schindler met Helen at one of Göth’s parties as she was serving the guests. He approached her and told her that, just as the Jewish slaves in Egypt eventually gained their freedom, so, too, would she. Indeed, Schindler added Helen and her two sisters (her mother had by then died in Plaszów) to his famous list of so-called essential workers that he managed to save from the clutches of the SS. Helen and her sisters, along with 300 other women on the list, left Plaszów and spent three harrowing weeks in Auschwitz. But Schindler protected them and they eventually ended up in Brněnec, Czechoslovakia, where Schindler ran another factory that was actually a front to shield the Jewish workers. They were soon joined by men arriving via Gross-Rosen.

Helen and her two sisters survived the war. Helen testified against Göth at the 1946 trial in Poland that led to his execution.Two days after the liberation, Helen met Joe Jonas, a fellow survivor, and they soon married. Jonas had an uncle in the U.S. who secured affidavits for Helen and her sisters. Helen and Joe arrived in 1947, settled on Long Island, and raised three children. Helen became an accomplished and successful electrolysist. She had an especially gratifying reunion in Israel with Helen Hirsch, her fellow maid in Göth’s villa. Joe died suddenly and tragically in 1980. Helen then married Harry Rosenzweig, who died in 2007. Helen died in 2018.

In 2004 Helen agreed to meet Monika Hertwig, Amon Göth’s daughter, after Hertwig wrote to her that “we have to do this for the murdered people.” Together they toured Plaszów and became the subject of the acclaimed film Inheritance, by James Moll.

Helen never lost her faith in God. She also remained convinced that, had there been a Jewish state during World War II, the mass murder of European Jewry would never have happened. She felt a deep sense of responsibility to tell younger people about the Holocaust and about the dangers of prejudice.

———

Additional readings and information

Helen’s unedited testimony at the Fortunoff Video Archive (available at access sites worldwide): https://fortunoff.aviaryplatform.com/r/dz02z12w09.

Books:

– Crowe, David M. Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account of His Life, Wartime Activities, and the True Story Behind the List. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2004.

– Keneally, Thomas. Schindler’s List. New York, NY: Atria Books, 1993.

– Martin, Sean. Jewish Life in Cracow, 1918–1939. London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2004.

– Pankiewicz, Tadeusz. The Cracow Ghetto Pharmacy. Translated by Henry Tilles. New York, NY: Holocaust Library, 1987.

Films:

– Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List

– James Moll’s Inheritance

###

Helen Jonas: My name is Helena Sternlicht, now Helen Rosenzweig Jonas. I lived in Kraków, Poland. I have two sisters. I am the youngest one. I was considered the child in the family. And my parents’ name was Lola and Szymon Sternlicht. And I had a happy home. I remember holidays and Friday nights we did candles and Kiddush. I have good memories.

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Those Who Were There: Voices from the Holocaust,” a podcast that draws on recorded interviews from Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. I’m Eleanor Reissa.

Helen Jonas was 14 years old when the Nazis occupied Poland. Within two years, her family was forced into a crowded ghetto, along with all of the Jews of Kraków. One day, Helen’s father was taken from their apartment by Nazi soldiers. She never saw him again.

It is now November 24, 1992, and Helen is being interviewed by Joni-Sue Blinderman at the Museum of Jewish Heritage office in Manhattan. Helen wears a dark brown jacket over a white turtleneck; a gold brooch adorns her lapel. Her carefully styled auburn hair highlights her widely set brown eyes.

Helen says that after her father was taken away, the rest of the family was sent to Camp Plaszów, a concentration camp built on the site of two Jewish cemeteries.

———

HJ: In order to delude the, the Jewish people, they called the camp labor camp. Because they told us we’re going to work. But, actually, it was a extermination camp—execution camp.

From the beginning, I was sent to clean the barracks. I was cleaning barracks until one day the commander, Amon Göth, who was in charge of the camp, walked in in the barrack and made, made his selection. He pointed a finger at me and ordered me to be his servant in his house that was located in the camp.

It, uh… He was the only one to make all the decisions in the Camp Plaszów. He was the only one that decided who is to live, who is to die. He was the most vicious man. He was so cruel. At the slightest provocation, I received the most cruel punishment. People feared him so, when they saw him from a distance, they ran. Physically, he was a very, very big man. He had to bend his head coming through the door.

We were not allowed to mingle with other prisoners. I was there with another young woman. And we had to share a room downstairs in his villa in the basement. He would ring this little bell to call me. And I ran so fast to those stairs up. And when I didn’t show up within split of a second, he, he would slap me so hard on my cheek that… my ears were ringing.

Joni-Sue Blinderman: Can you describe more episodes for us?

HJ: Certain times, certain nights when he didn’t sleep and was drinking all night, and I would see him walking out, six o’clock in the morning, before the people called prisoners were to go to work. And he would shoot on a random. And he would come back. And I see him whistling and laughing.

He had two big dogs, Big Dames [sic]. And he would train them to attack people. He used to put this big glove on his arm and train them. And frequently he would call me out to watch him in the backyard, how he ordered the dogs to chase prisoners and tear them apart.

They were like little horses, and they chased the people. And he yelled out. And then they started chewing and grabbing on the people. I can never forget it. And his face, when this was done, this face of pleasure.

I remember at one time he was standing near the window and called me. He was holding a rifle toward the window. And he said, “You see those stupid dogs down there?”—meaning our people. They were digging ditches there and carrying rocks. And it seemed like they probably stopped for a while. He said, “If they don’t start in five minutes, I’m going to start shooting.” Well, I ran out so quick from the villa. Instead of going around the road to get down, I slid down. There was a very big hill down. I slid on my back because I was worried that I might never make it to get down on time, to warn them that he’s watching. And he would probably have done it.

He told us he hates Jews. And he will always be hating Jews. And because we are Jewish, he has to hate us. Even if we do the job well, he still has to hate us.

I would say that every day was the most frightened day of my life. He had his mistress with him, and she was in charge of giving us orders.

JB: Do you remember her name?

HJ: Ruth.

JB: Was she a non-Jewish woman?

HJ: Of course. She was, she was a German. He lived a luxurious life. He had company constantly. He had his mistress. And he had the two maids, the Jewish slaves, which one of them was I.

He was having a lot of parties in his villa with a lot of Gestapo. And he would entertain all night, sometimes till dawn. And I had to serve all night. And each time I walked in the room, I was humiliated by those drunkards calling me names.

Schindler was part of the company he entertained. Somehow Schindler would come down to the kitchen and, uh, try to always to give, give me comfort. I couldn’t figure him out. I, I was frightened. I saw him upstairs with all the Gestapo, laughing and drinking and carrying on. In here, he would come down and put his hand on my arm. And I was so frightened.

And he would tell me, “Don’t you worry. Don’t you worry. You’ll be alright.” He would take me to the window. And he would tell me, “You see those Jewish people, you people? They work. They carry stones. They carry rocks, just like in Egypt. Remember when the Jews were in exile, and then they were freed?” He said, “That’s what’s going to happen to you. You’re going to be free of the hell.” But I really didn’t trust him.

I was not allowed to mingle with the prisoners. And I, I took big chances to go see my mom. I had to go see my mother. I never told her about my conditions. I—but I’m sure she knew. My sisters and my mother were in the barracks. I was alone with my friend sharing the room in the villa.

JB: What was your friend’s name?

HJ: Her name was also Helen. But he gave us both different names. He called her Lena. And he called me Suzanne. She was older. She was older. She spoke fluently German. And she taught me a lot. She protected me many times.

I was really a child yet, since I really came from a home that I was the baby in the family. I had to grow up so rapidly. There was no time for me to be a child.

A lot of people felt that maybe it’s easier for me because I have my clothes. I have my food. It wasn’t like that. It was nothing like that. It was so frightening. Even during the night, he would call. And something I said that wasn’t perfectly right or to his liking, the beat—the beating began. So many time I was pushed down the stairs. And, and my face was swinging from left to right. His one hand was like three of mine.

Fortunately, I have always believed in God because the very few times that I saw that he was trying to kill me, instead he hit me or pushed me, so it was meant for me to live.

I was on the third floor in the villa and doing my chores this one particular time when I looked out the window. I saw a lot of women walking toward the end of the camp, the entrance of the camp, with white kerchiefs on.

I ran down and I said to my friend—I grabbed a white kerchief, and I said to her— “I’m going because I see a lot of women. I think there is deportation.” And I said, “If I—if, if my sisters are there, and I can’t get them out, I’m going with them.”

And she tried to stop me. She says, “Wait! Wait! We’re going to see what we can do here.” I said, “No, no. I have to go.” I ran so fast. I was just running, and my sisters were in the middle of the transport.

I don’t know, foolishly enough, without thinking, I ran straight to him. He was at the entrance of the door, next to the baggage cars, cattle cars, where they were loading the women on to be sent away. And I approached him.

I told him that my sisters are in the transport. And he swung his arm at me and hit me so hard. And he says to get away, to get away because he’s gonna kill me. All of a sudden, I heard a voice behind my back telling me, “Move away. Move away. I tell you something.”

Well, you see, I don’t know. For some reason, some of the SS and some of the Jewish police, knowing that I work for him, for the commander of the camp, I was able to have some privileges, here and there. And I heard this voice in German telling me to “Move, move, move!” And he’s going to tell me something.

And then a very quiet voice was telling me, “Don’t turn around. Don’t look at me. Just walk. Walk.” And, and I’m walking along. He says, “Don’t look at me. Don’t look at me. Don’t look back.” And he said, “Tell your sisters to gently move back very slowly because we just got orders that we do not have enough cars for the people to send away. Therefore, we’re going cut some people off from the end. So tell them to move back, but very slowly. And don’t look back.”

Simultaneously, my friend, knowing that I didn’t come back, she assumed that, yes, my sisters are in the transport. She woke up his mistress and asked her to call the Jewish police that was on other end of the transport entering the barracks, to give an order to get my sisters out.

Well, she fought her so hard. She said, “I cannot do it with my—without him. Please, don’t ask me to do it. I can’t do it.” But my friend insisted, and she said, “You must do it for us. We worked for you for such a long time.”

She practically forced her to get to the phone and call the Jewish police. And that’s what happened. Simultaneously, as my sisters were moving back, the Jewish police came to take ’em out. And that’s how I have my sisters.

She always kept telling us, Ruth, his mistress, that she has to tell him someday when she’s goin’ get him in a good mood because her conscience bothers her. We pleaded with her, “Please, don’t tell him. Please.” She says, “No. I can’t live with it. I have to tell him. But I’ll get him in the right mood.”

Well, this was the night when she told him. And he came looking for me, with a gun in his hands. It seems because—excuse me—because I wasn’t there, he, he beat her up.

JB: He beat…?

HJ: Helen. She beat—he beat her up so badly. This woman still cannot hear in one ear, due to the pounding with a gun. I came in the morning. I was trembling like a leaf.

And all of a sudden, I hear the call. And I come up, and he’s in the bedroom. He’s looking at me and with a sadistic smile, he said, “You lucky dog.” And I didn’t say a word, because I was so frightened that he’s goin’ go afterwards and look for my sisters. But he didn’t.

I had been connected with a group of resistance in Camp Plaszów. They were connected with the resistance group in Kraków. By ways of taking out certain information from his cabinet drawer. They were very helpful to the people of resistance. I also have gotten copies of certain passes from the camp that were given to my friend who is in charge of the group. And because of those passes, some people could move and get out of the, of the, of the camp.

JB: Where would you get the passes?

HJ: He had, he had them in his cabinet, locked. But I had keys to all the cabinets. And I made copies. They supplied me, my friends supplied me in their little copy equipment that I could copy them.

It was very fearful because he used to come, he used to ride a horse frequently, a white horse. And he would show up very frequently, and I wouldn’t even know when, but those were things that I felt I had to do.

Many moments I felt like he probably one day will say, “I don’t need you anymore.” And that would be the end of us. And toward the end of the—toward the end of the Camp Plaszów, when Russians were moving closer to the borders, he did kill some of the people that were close to him.

JB: Some of the Gestapo?

HJ: His secretary. His—no, the Jewish people that worked close to him in the office. He killed a few of them. And we knew that we goin’ be killed as well.

One time I, I heard the doorbell, and I opened the door, and two civilians came in and asked for him. And I called him, and he came down. And they showed him their identification. And he moved back, reached for his hat and his belt with a gun, and walked out in center with them. I didn’t know what was happening, but I ran down to my friend. And I said it looked like he was arrested.

We were alone for a couple of days. And, um, nothing was happening until I received a phone call from him. It was unbelievable, like a different voice. He said to me to pack some of his personal belongings, and somebody is goin’ be pick—picking it up.

JB: When did this happen?

HJ: This was—happened just before the liquidation of Camp Plaszów.

JB: And do you know now who these two people were?

HJ: Yes. We knew because we found out that he was arrested for black market activities. He did take a lot of the belonging from the prisoners, from the executed prisoners. There were jewelry. There were gold. Some dentists were pulling out gold teeth from the executed prisoners. It seems like he took a lot for himself. And, and other SS had reported him. Fortunately, he was arrested by his own Germans. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be here to tell this story.

And that’s where Schindler came back and said to me and my friend as well, “You’re coming with me. I am building a factory in Czechoslovakia, and you goin’ be on my list.”

Fortunately, he remembered me and my friend. And he came in the right time, knowing that Göth is arrested, that he can take us along. And, um, I was able to take my two sisters along with me. My cousins, my grandmother, my aunts were all gone.

JB: And your mother?

HJ: My mother? My mother was, was very ill in the camp. Due to lack of medication she died in camp.

Schindler, um, I personally, uh, had mixed feelings about him. I know he saved thousand people and saved me and my sisters. And, uh, I think he’s a savior. But he was a Nazi.

You know, I saw him in the villa in many ways that he was holding hands with Amon Göth, and laughing with all of them, and, and drinking, and behaving like the rest of them are. I couldn’t connect the two together. I guess he was using them as well.

I feel that, um, he was a opportunist, but he saved us. And, um, if not for him, I don’t think I would be able to, be able to tell this story. I don’t think I, I… I’m having a very hard time talking about it, however, I, I think that we have to keep remembering it with each generation so we can guard the world against another Hitler.

I try very hard not to remember, because I have a lot to live for. I have great three children, and, and four grandchildren. And, uh, I look forward to a, to a normal life as best as I can. I try not to hate, but I will never forget it. The pain is there, and never leaves me.

———

ER: After the war, Helen Jonas testified against Amon Göth at his trial in Kraków. Göth was found guilty on multiple counts, including homicide. He was sentenced to death and hanged.

Helen immigrated to the United States in 1948 and settled on Long Island, where she raised her family. Helen spoke frequently about her experiences during the Holocaust. She appeared on news programs and was a guest speaker at numerous high schools, colleges, and organizations.

Helen was featured in a 2006 documentary called Inheritance, a film about Amon Göth’s daughter Monica. Monica and Helen are shown meeting for the first time at a memorial on the site of the Plaszów concentration camp.

Helen Jonas died on December 20, 2018, in Boca Raton, Florida. She was 93 and was survived by two of her three children, four grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. Her son Steven said his mother believed that you need to forgive but not forget.

To learn more about Helen Jonas, please visit our companion website at thosewhowerethere.org. That’s where you’ll find episode notes, a full transcript, archival photographs, previous episodes, and background information on the Fortunoff Archive and the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

“Those Who Were There” is a production of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, which is housed at the Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Department in New Haven, Connecticut. This second season is a co-production with the Museum of Jewish Heritage—A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, New York’s contribution to the global responsibility to never forget. The museum is committed to the crucial mission of educating diverse visitors about Jewish life before, during, and after the Holocaust.

This podcast is produced by Nahanni Rous; Eric Marcus; the Fortunoff Archive’s director, Stephen Naron; and Treva Walsh, collections project manager at the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

Thank you to audio engineer Jon Gordon. Thanks, as well, to Christy Bailey-Tomecek, Joana Arruda, Noa Gutow-Ellis, and Inge De Taeye for their assistance. And thank you to Sam Kassow for historical oversight, and to photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael Leclerc, and our social media team, including Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Sara Barber. Ljova Zhurbin composed our theme music. Thank you, as well, to Steven Jonas and Vivian Delman for providing family photographs and background information about their mother.

Special thanks to the Fortunoff family and other donors to the archive for their financial support.

I’m Eleanor Reissa. Thank you for listening.

###