By Dr. Samuel Kassow

Heda Margolius Kovaly spent most of her life in Prague. She was born there in 1919, shortly after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire, and grew up in a democratic Czechoslovakia. In 1939 she witnessed the German takeover of Prague and, after surviving the Lodz ghetto and Nazi camps, returned to her native city in 1945. Five years later, she saw her idealistic husband Rudolf, another Holocaust survivor, fall victim to Stalinist terror and endured harassment and persecution at the hands of the Communists. After spending many years with her second husband in the United States, she finally returned to Prague, where she died in 2010.

Heda grew up in a well-to-do family. Her father, Ervin Bloch, moved from his parents’ farm to Prague before the First World War, during which he fought in the Habsburg army, was wounded, and taken prisoner by the Serbs. When he returned from the war, Ervin rejoined the Waldes Company in Prague, a manufacturer of sewing devices and clothing hooks, where he became the general manager. In 1916 he married Marta Diamant and they had two children, Jiri and Heda. Heda had a very large family, with many uncles, aunts, and cousins. Only she would survive the Holocaust.

Ervin was a cultured man who was friendly with Max Brod and Franz Kafka. He took a keen interest in modernist art and architecture. Like many other Jews of his time and class, he was a fervent supporter of Czechoslovakia’s first president, Tomas Masaryk, who sought to build a nation based on the principles of democracy, tolerance, and decency. The success and stability of interwar Czechoslovakia convinced the Blochs that an era of liberal humanism would redeem the loss and destruction of the recent world war.

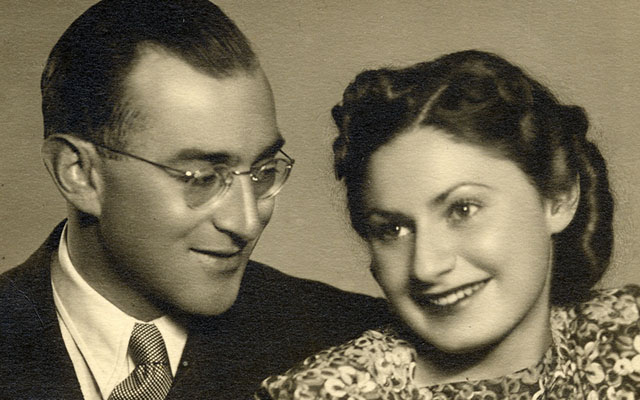

Heda went to fine schools, traveled widely, and learned foreign languages. She first met Rudolf Margolius, who also came from a well-to-do Czech Jewish family, in 1932, when she was only 13. They married on March 13, 1939, two days before the Germans occupied Prague and established a “Protectorate” over the Czech lands of Bohemia and Moravia. Slovakia became an “independent” German puppet state.

Heda’s father, like most of his generation, could not understand how in the space of a few months, their nation, abandoned by its allies in 1938, could experience the frightening transition from liberal stability to Nazi terror. The world they had known—its norms, rules, laws, its high culture—collapsed in a matter of weeks and months. To the very end, until their death in Auschwitz in 1944, Heda’s parents struggled, in vain, to grasp how this could have happened.

The Nazi persecution of Czech Jews escalated very quickly, through the loss of employment and businesses, the imposition of the yellow star, and expulsion from schools. Heda’s family was forced to move to a smaller apartment in 1939. Heda testified that the Czechs behaved decently during this time (although there are other survivors who were not as positive).

The deportations of Jews from Prague began in 1941, primarily to Theresienstadt and the Lodz ghetto. These in turn were way stations to the gas chambers of Treblinka, Chelmno, and Auschwitz or the shooting pits of Riga and Minsk. Of the 88,000 Jews who lived in the Czech lands in 1939, only 10,000 survived. The names of 77,297 victims of the Holocaust are etched on the walls of the Pinkas Synagogue in Prague.

In October 1941, the Nazis sent 20,000 Jews from the Reich and the Protectorate to the Lodz ghetto, including Heda, Rudolf, and their parents. As Heda points out in her testimony, the Lodz ghetto was unique in several respects. While most Jews in the Warsaw ghetto managed to survive thanks to the massive smuggling of food paid for by a lively trade with the Poles over the wall, the Lodz ghetto was hermetically sealed. No food was smuggled in. There was no “Aryan side” to trade with since Lodz was incorporated into the German Reich and most of the Poles had been expelled. Jews in the ghetto were totally dependent on the all-too-scarce food that the Germans allocated. Sanitary conditions were frightful.

The Lodz ghetto was highly regimented. Enormous power rested, for a time, in the hands of the autocratic Chaim Rumkowski, who was convinced that the only way to buy time and save Jewish lives was to turn the ghetto into one massive factory in service of the Germans. When he could, Rumkowski tried to help Jewish children by maintaining schools and providing extra food. But he was powerless to stop the deportations to the gas chambers, which began in 1942. During that year, in three waves, 71,000 Jews were deported to nearby Chelmno.

An especially traumatic moment in the history of the Lodz ghetto was the “total curfew”(Gehsperre) in early September 1942. (Heda mistakenly said it took place in the spring of 1943.) Rumkowski wept as he told the ghetto population that the Germans demanded the deportation of all children under 10, all adults over 65, and, if that failed to meet the quota of 20,000, all people who looked weak and sickly. For one week, no one was allowed to leave where they lived, while the Germans went from building to building tearing away the children and carrying out selections in the courtyards.

Many Jews in the ghetto loathed Rumkowski, but they grudgingly gave him credit for his energy and his ability to wheel and deal and show the Germans that the ghetto was an asset. Indeed, Lodz was the last ghetto that the Germans liquidated. It survived until August 1944, when its remaining Jews, including Heda and Rudolf, were deported to Auschwitz.

Counting the deportees from the Reich, the Czech lands, and Polish provincial ghettos, about 200,000 Jews passed through the Lodz ghetto. A total of 43,743 died of sickness and hunger; 15,000 were deported to labor camps, where most of them died; 80,000 were deported to Chelmno (in 1942 and during a short period in 1944); and 67,000 were sent to Auschwitz in August 1944. At that late date, about one in three Jews, including Heda and Rudolf, were selected for forced labor, while the rest, including Heda’s parents, were gassed. All in all, about seven to ten thousand survived.

On the ramp at Auschwitz, Heda and Rudolf were among the 20,000 or so Jews who were spared the gas chambers. After some time in Auschwitz, they were sent on to different labor camps: Rudolf to Dachau and Heda to Gross-Rosen. Heda used a forced march from Gross-Rosen in March 1945 to make a daring escape to Prague. Alone and without papers, she vainly asked old trusted friends to help her. Most were too afraid and refused. Finally, one did. Heda survived to see the liberation of Prague and then learned that Rudolf had also survived. They were reunited in 1945.

In her book The Taste of Ashes, Marci Shore quotes the famous Czech writer Milan Kundera: “And so it happened that in February 1948 the Communists took power, not in bloodshed and violence, but to the cheers of half the population. And please note: the half that cheered was the more dynamic, the more intelligent, the better half.” Indeed, by the time the Communists took power in that bloodless coup in February 1948, Heda and Rudolf had already joined the party and they were certainly among those who cheered the takeover.

Why did they become Communists at a time when anyone who cared to look knew all about the reign of terror in Stalinist Russia? One reason was that, like many Czechs, they could not forget how the western democracies had abandoned Czechoslovakia at Munich. As Jews and Holocaust survivors, they also admired the Communists they had met in the camps for their idealism, for their discipline, for their determination to resist. And they owed their liberation from the Nazis to the Red Army. They believed that the Communists would bring about a better society free of exploitation, racial hatred, and antisemitism. But as Heda admitted in her original testimony, “We were fooled… We didn’t realize that the only alternative to fascism was democracy.”

Rudolf quickly climbed the Communist ladder of power. He was idealistic, believed in the party, and worked hard. In 1949 he was promoted to deputy minister of foreign trade, in which capacity he handled important and sensitive negotiations with Britain, Sweden, India, and other countries. Heda and Rudolf’s only son, Ivan, was born in 1947, but Rudolf had little time to spend with his family. Now members of the party elite, Heda and Rudolf had a car, a nice apartment, and… new worries. Old friends begged Rudolf to leave his job. There were growing signs of antisemitism in the party, a purge was in the air, and he was too vulnerable. But he waved these worries aside, even when Heda urged him to quit.

Rudolf was arrested on spurious charges in January 1952 and was one of the 14 defendants in the well-known Slansky trial, which took place in November that same year. The Communist press pointedly emphasized that 11 of the defendants were of Jewish origin. Rudolf was forced to sign a confession and parrot his lines at the trial, which was broadcast on live radio. He was hanged in early December 1952.

Heda became an outcast. She was harassed by the authorities, which made it hard to properly care for her son. Thanks to the help of a few friends, she managed to support herself and Ivan and, in time, she became a writer and translator. Her son Ivan would go on to become a well-known architect. He also wrote a memoir about his parents entitled Reflections of Prague: Journeys Through the 20th Century.

The lives of Heda Kovaly and her husband Rudolf Margolius were marked by a double betrayal. The first was at the hands of the western democracies that abandoned their nation in 1938. The second was at the hands of the Communists, who they both hoped would redeem a nation and a world scarred by fascism and war. Instead, Rudolf survived the Nazis only to die at the hands of Stalinist antisemites, while Heda had to endure decades of privation and struggle. But in the end, through her writings and testimonies, she left a lasting legacy.

A note about the song Heda sings: In the episode, Heda sings the refrain of “Yidl Mitn Fidl,” a well-known Yiddish theater song taken from the Polish 1936 movie of the same name. The film was directed by Joseph Green and starred Molly Picon. The song lyrics were written by the Yiddish poet Itzik Manger. The lines Heda sings translate to “Yidl with the fiddle / Khaykl with the bass / We play a song / In the middle of the street.” Heda’s lyrics are a variation on the original version: “Yidl mitn fidl / Arye mitn bas / Dos lebn iz a lidl / To vozhe zayn in kas?” or, in English, “Yidl with the fiddle / Arye with the bass / Life is a song / So why get angry?”

———

Additional readings and information

Kovaly, Heda Margolius. Under a Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968. Cambridge, MA: Plunkett Lake Press, 1986.

Margolius, Ivan. Reflections of Prague: Journeys Through the 20th Century. Chichester, England; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2006.

Shore, Marci. The Taste of Ashes: The Afterlife of Totalitarianism in Eastern Europe. New York, NY: Crown, 2012.

Heda’s unedited testimony at the Fortunoff Video Archive (available at access sites worldwide): https://fortunoff.aviaryplatform.com/r/xs5j960m47.

###

Heda Kovaly: My name is Heda Kovaly. I was born in Prague. My father’s name was Irving Block, my mother was Marta, and I had a brother, George. My father had five sisters, and my mother had a brother and a sister, and there were a lot of children. And as far as I know, I am the only survivor.

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Those Who Were There: Voices from the Holocaust,” a podcast that draws on recorded interviews from Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. I’m Eleanor Reissa.

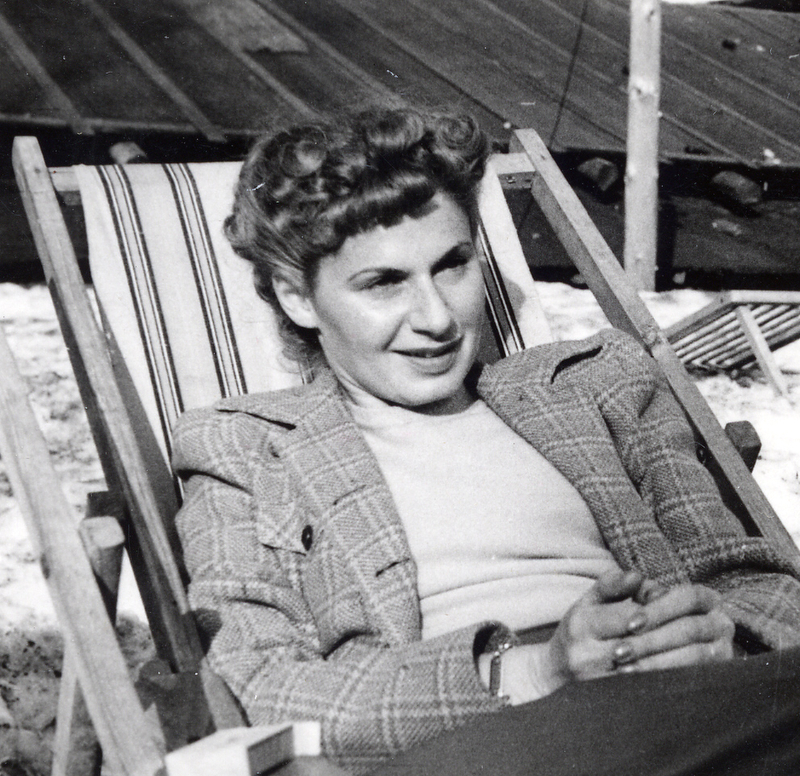

It’s July 22, 1980, and Heda Kovaly is sharing her story with interviewer Laurel Vlock in a television studio in Boston, Massachusetts. Heda is an elegantly dressed woman with high cheekbones, hazel eyes, and blond wavy hair. She wears a tailored, cream-colored blouse—a thin gold chain loops just beneath her clipped-on microphone. She holds a balled up tissue in her right hand.

In October 1941, shortly after Heda’s 22nd birthday, the Nazis ordered a mass deportation of Jews from the Czechoslovakian capital, Prague. Up until then Prague had one of the largest and oldest Jewish communities in Europe. Heda, her parents, and her husband, along with thousands of other Jews, were held in Prague’s Exposition Hall for two days before being transported to the Lodz ghetto in Poland.

———

HK: It was the first taste we had of this incredible thing of, all of a sudden, not being free, not being able to move around, not even being able to lay down, because there was no room. There was a woman I knew—an older woman—who went completely crazy. There were babies. There were people, very sick, who died there, right there. It took us several days to get to Lodz.

Laurel Vlock: How did you get there? Did you have to march there? Walk there?

HK: We went by train. I remember these horrible screams, because they always… They used to come from outside into the wagon, and they slammed the doors. And sometimes they hurt people’s fingers or they took someone out of the train and they beat them up. And this was the first time I heard people screaming with pain.

So everybody was dreadfully thirsty. And they let us get out of the train to bring some water—the young people. So they said, “Out and get the water.” And I remember how we got out of the train and there was some, a pile of gravel. And there was this beautiful flower growing out of this mess. And it was a purple, beautiful, gorgeous flower. And I thought, This is the last flower I’m going to see.

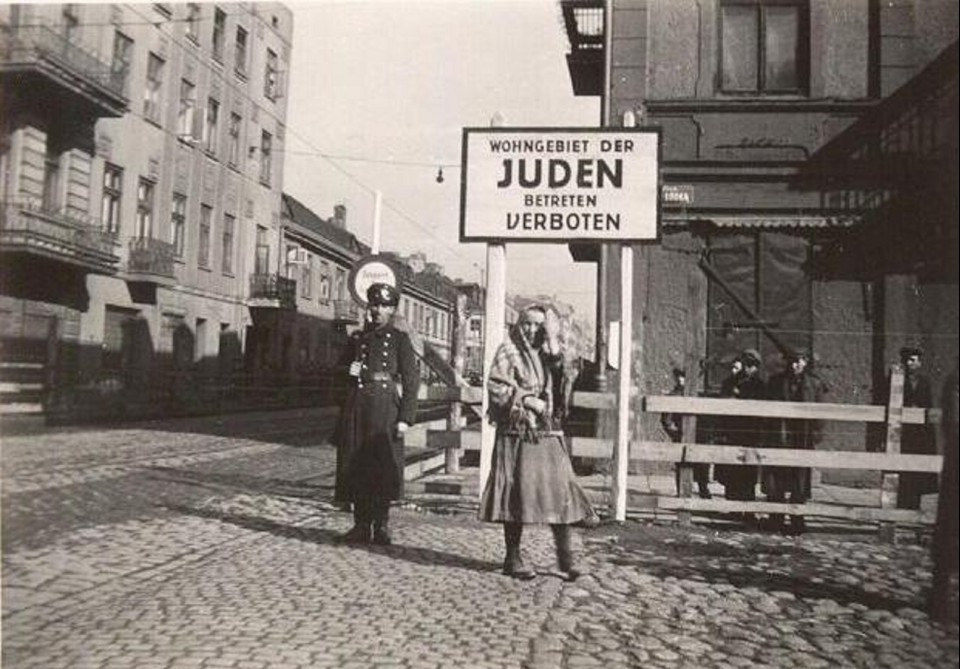

So we came to Lodz. It was October. And we walked from the station, and then, for the first time, we saw the Polish Jews already there, barefooted in the snow, looking dreadfully undernourished and sick.

Lodz had this part of, the slummy part of the town, they made this wall around it—it was a ghetto. There were German soldiers guarding it day and night. And there was this wall. It was just wooden, part wooden, part brick walls. But nobody could leave. You couldn’t escape, and it was so claustrophobic and there was absolutely not enough food.

At first, people got these dreadful edemas, the swollen feet, and then they got tuberculosis, then it was meningitis. And people died. And the funny thing is, the first to die were the strong, young men, because they needed more nourishment than the thin girls.

People were shot, people were executed. They executed… I don’t know how many people, because I never had the courage to go and look. They let them hang on the square for several days. And my mother went there, because she said someone has to pray for them.

From time to time, the Germans came and they took people away. Sometimes they only took old people, and sometimes they took children. And the worst was in the spring of ’43, I think. The Germans said we should all go, where we lived—nobody goes out. And it took several days. Many people died because they couldn’t get anything to eat. Most, our main nourishment was the soup we received in the place where we worked. It was usually turnip. And when we couldn’t go to work, we didn’t get anything to eat, so many people died at that time.

And the Germans went from one place to the other. And there was this, always this officer, a German officer, who said, “This person, go this way, and this person goes back.” And they took all the old people, and the children, and took them away. Most of the children were taken away at this one big transportation of the Jews to Auschwitz.

And I was very worried about my parents, but they somehow managed to… We were lucky, in this way. They survived even this. And after it was over, the Germans said, “Now everybody can go out. You can leave your homes and go out.” And so of course, people were starved to death, and they went out and tried to get something to eat, somewhere… We even ate grass and things like that. And when so many people were on the streets, they came back and started shooting. And I thought, My god, father, mother. And I ran home. And the shots just were, you know, all over me. I don’t know how I made it home, but my parents did it, too. They’d made it home, too.

And then something really funny happened to me, because the next day I got some stuff that we could eat. And there were such places where you could cook something, because you didn’t have any heat at home. And at Lodz, whenever there were Germans walking through the streets, all the Jews were supposed to clear away and not be on the sidewalk. Men had to take off their hats, women should bow and to leave them with the sidewalk.

And I was walking with this pan in my both hands for water, and some, some grass, or turnip, or whatever I got. And there were these three Germans who came to me, walking through the street. And I thought, Well, if I do it, I really am a Schweinehund. I am really less than human. I won’t do it. And so I walked with the pot in my hands. And they were so surprised that they let me go. They gave, gave way to me. They stood, looked after me, and I walked like a machine, and they let me go. Usually, they shot you.

LV: When they took you to Auschwitz, do you remember the trip and what… Why did you finally have to go?

HK: I think that the Germans had to face a problem. The front—the Russians—were actually very close at that time. And they didn’t want any trouble in Lodz. So they sent the generals to talk to us. Or maybe he wasn’t a general, he was a colonel. I don’t know, but he had a beautiful uniform, full of gold and all that. And he, we were gathered at the main square, and he said, “Ich gebe euch mein Ehrenwort eines deutschen Offiziers.” “I give you my word of honor, of a German officer, that nothing is going to happen to you. You are going to be moved to a safer, better place. You will stay together. And there is no reason to panic or to start anything. You’ll be better off than you are now.” And that was the moment when my father said, “Okay, you don’t know what it means, a word of honor for a German officer. They can’t break a word of honor.”

The trip to Auschwitz was just the most horrible thing. It was hot. They didn’t let people out. The people were dying. They didn’t let anybody out to go to the bathroom. It was a nightmare. And at the end of the nightmare, we were in Auschwitz. And we went out of the, out of the train. Right there, they started dividing women from men. And I only could see my father’s face. And he said, “Take care of mother.” And that was all. I didn’t see him walking away. It was just such a crowd, you see?

And we walked, hand in hand, with my mother. And there was Dr. Mengele. And he showed my mother to the right side. And I wanted to go with her. And there was a soldier, and he threw me to the ground and said, “You stay here.” “Where are these people going? What’s going to happen to them?” And he said, “Don’t be hysterical. And if you ask, you aren’t going to see them again.”

I don’t know how long I was in Auschwitz. It’s all like a nightmare. It’s… I only see very vividly… I can, I can see pictures, like in a movie. You know, I can see details, but there is no connection.

I remember one night, I crawled out of the barracks. Everybody was asleep. And there were these gorgeous nights. You know, it was summertime. It was hot. But at night, it was cool. And these stars, these beautiful stars. And the wires made this sound. It was like music, you know? And I was lying there in the dirt. And there were the stars. And there was this music.

And I remember this girl who was ordered to sing. And she did. It was something like, [singing] “Das Yidl mitn fidl / Der Khaykl mitn bas / Shpiln mir a lidl / In mitn fun der gas…”

LV: Why did she have to sing? Why did…

HK: Because the kapo said she wanted us to be happy. She want the barrack to be happy. I think it was the most dreadful thing for her, to stand there, in this horror. Probably, her mother, father, everybody killed, and she had to sing. At least we didn’t have to sing.

I remember the last day. They said if, umm, if a train comes, during the night or the next morning, we will go in another concentration camp. If the train doesn’t come, we will go to the gas chambers.

And the last night I couldn’t think about anything except my mother. Moje máma. It was, again, such a beautiful night. And I remember sitting on the ground. And I remember how I held up my hand and there was this big… You know the dandelions? And it came to me and it landed on my hand. And I thought, My mother, she’s here. I think maybe she’d just died that moment.

And it was very strange how I got out of Auschwitz, if you want to hear that, because it’s quite funny. Because next day, the train came. And so then we walked five abreast to the, to the train. And the most important thing in the concentration camps was to keep five together. Always. Because if you didn’t, nobody knew what’s going to happen to you.

Everybody, all the old-timers told us, “Stay five together, always.” So we marched and all of a sudden, I saw we were not five, but six. A girl who was in front sort of got panicky and ran, and stood in my row, so that we were, instead of five, we were six. And someone gave me a shove from, from, from the back. And I started running. And all of a sudden, someone took my hand and drove me into the row from which this girl ran away, because there were only four there and they took me in.

They counted the girls who are going to be in the, go into the train. And they stopped in front of me. I was the first row to stay behind. And they all started shouting, “Turn around,” and so on. And from the train, a girl fainted. And the German soldier said, “Another, another piece.” They always—“Stück.” “Another piece.” So since I was the first, I went. That’s how I got out of Auschwitz.

Listen, it was all chance. Some people died, some people were killed, some people survived. There is no way to say, “I survived because…” You can kid yourself into believing that you are more tough, you are more stronger, or there was something special about you. No. You were luckier than the other ones. And I seem to have been, in this way, lucky. But it wasn’t so easy to have lost everybody.

I think everybody who survived the way I did, we sort of don’t feel at home in this world anymore, because you never forget. But you learn to live with it. And that sets you apart from other people. Not that you can’t enjoy yourself. On the contrary, when I am happy, I am so happy because I know how horribly unhappy I can be. But there is a certain—it’s like a music in the background. You never get rid of it.

———

ER: After Auschwitz, Heda Kovaly was transported to another concentration camp where she worked in a brickyard. Toward the end of the war, she and her fellow prisoners were taken on a forced march out of Poland and across Germany. That’s when Heda escaped and made her way back to Prague.

It was February 1945, and Prague was still occupied by the Nazis. Heda went door to door asking her former friends and neighbors for help, but they refused—too terrified to be caught sheltering a Jew. Finally, a friend connected her with the Czech resistance and they helped her hide until the war’s end.

After the war, Heda was reunited with her husband, Rudolf Margolius. Rudolf joined the Communist Party and was given a prominent post when the Communists took power in 1948. Four years later he was one of 14 party members accused of “anti-state conspiracy.” Eleven of the accused were Jews. Rudolf was executed.

Heda and her second husband later emigrated to the United States, where Heda worked as a writer and translator—and as a reference librarian at Harvard University. After nearly three decades in America, they returned to Prague. Heda died there on December 5, 2010. She was 91 and was survived by her son and five grandchildren.

To learn more about Heda Kovaly’s remarkable life story, please visit thosewhowerethere.org. That’s where you’ll find additional background information, photographs, and a link to Heda’s memoir, Under a Cruel Star.

To hear more from “Those Who Were There,” please subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. You can also go to thosewhowerethere.org.

“Those Who Were There” is a production of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, which is housed at Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Department.

This podcast is produced by Nahanni Rous, Eric Marcus, and the archive’s director, Stephen Naron. Thank you to audio engineer Jeff Towne and to Christy Tomecek, Joshua Greene, and Inge De Taeye for their assistance. Thanks, as well, to Sam Kassow for historical oversight and to our social media team, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Ljova Zhurbin composed our theme music.

Special thanks to the Fortunoff family and other donors to the archive for their financial support. I’m Eleanor Reissa. Thank you for listening.

###