By Dr. Samuel Kassow

Sometime in April 1945, a young African American GI, Leon Bass, entered the notorious Buchenwald concentration camp and saw piles of dead bodies and prisoners so weakened that large numbers of them would die in the days and weeks following the liberation. This encounter was seared into his memory, but it would be decades before he began to talk about what he had seen and what it meant to him. In the course of that long journey, he came to understand that the empathy he felt for those debilitated prisoners stemmed in part from his own struggle with Jim Crow—and from his growing awareness that racism and hatred knew no national boundaries and, unless checked, would continue to claim new victims. In a turbulent era of American history, when the country was wracked by the Vietnam War, student protest, and racial turmoil, and at a time of escalating tensions between blacks and Jews, Leon stepped forward to tell what he saw. In doing so, he helped personify what the French scholar Annette Wieviorka calls “the era of the witness.”

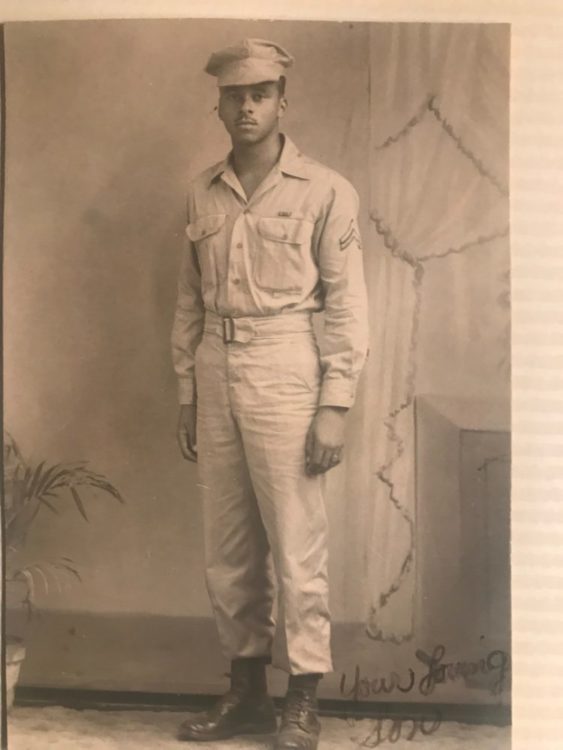

Leon was a soldier in a segregated army, a young man who had to struggle against unrelenting discrimination and humiliation. He was born in Philadelphia in 1925, one of six children. His parents, Henry and Nancy Bass, were poor sharecroppers from South Carolina, who like millions of other African Americans joined the great migration to the north in search of a better life. Henry had served in France in World War I and returned from Europe a changed man. As a pullman porter, Henry endured his share of humiliations in the Jim Crow era. But his dogged determination to fight for his dignity left a lasting impression on his son. (Indeed, few black leaders fought harder for civil rights in those difficult times than A. Philip Randolph, head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Henry’s hero.)

Growing up in the Depression was hard for everybody, especially for blacks, but Leon Bass was lucky to have parents who gave their children a loving home and to have gone to a public school that, though segregated, had caring teachers who taught young black pupils self-respect and pride. Role models like Mary McLeod Bethune came to assemblies to remind these young people not to lose hope. But certain anomalies could not escape Leon. When he went to the movies he had to sit in the balcony. While the Pledge of Allegiance talked about “liberty and justice for all,” he was old enough to know that this wasn’t exactly true.

Leon enlisted in the Army when he was 18, in 1943. World War II had spurred black America on to redouble its struggle for equal treatment. Threats by A. Philip Randolph and other black leaders to lead a march on Washington persuaded President Roosevelt to sign Executive Order 8802 banning discrimination in war industries. William H. Hastie, dean of the Howard University School of Law, was appointed a civilian aide to the War Department to help assure equal treatment of blacks in the military. (Frustrated, he resigned in 1943.) Severe housing shortages in American cities, swollen by an influx of war workers, led to promises of black access to new housing projects.

But most of these promises were not kept. The war exacerbated rather than allayed American racism. Opposition from white workers and unions ensured that black workers mostly languished in menial jobs, unable to get the training needed to qualify them for skilled trades. Bloody race riots broke out in Detroit, New York, and other cities.

Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Army Chief of Staff George Marshall were determined to maintain segregated armed forces, where blacks would serve in all-black units, officered by whites, that would perform service and labor rather than combat roles. In time, because of a growing manpower shortage, higher-than-expected casualties, and unrelenting pressure from black leaders (as well as from Eleanor Roosevelt), some of the barriers came down. Some black combat units were organized, like the Tuskegee Airmen, the 92nd Infantry Division, and a few armored units. During the Battle of the Bulge, many black soldiers were hastily transferred to combat units where they served with distinction. By the end of the war, a few blacks were promoted to higher rank, like Brigadier General Benjamin Davis.

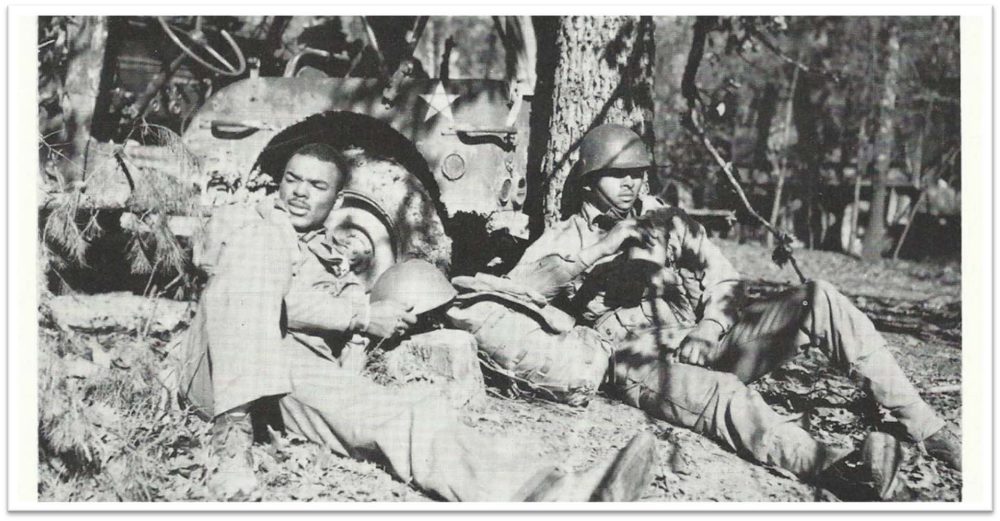

But these improvements were slow in coming, and Leon’s experience in the Jim Crow army was typical. He served in the segregated 183rd Engineer Combat Battalion, which was commanded by white officers. “There was no love lost,” Leon recalled, between the black soldiers and their white officers. Though he was in uniform, , he had to remain standing on long bus rides just like other black passengers, while seats in the white section of the bus were left unfilled. He watched as German POWs were allowed to sit at the same lunch counters that denied him service. Although his unit did yeoman service, especially in building vital bridges during the Battle of the Bulge, Leon became increasingly bitter. The irony of life in a Jim Crow army that professed to be fighting for freedom and equality did not escape the young soldier. While race relations were somewhat better on the front line, in the rear areas brawls between whites and blacks were common.

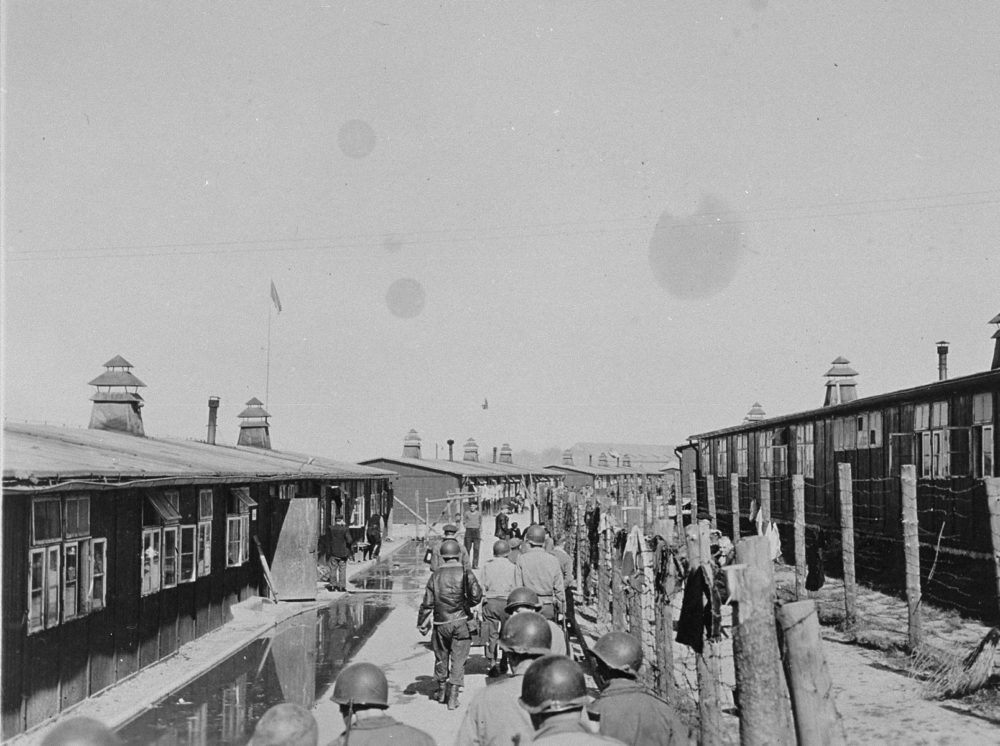

Nothing that Leon had encountered before or had heard prepared him for what he saw when he got to Buchenwald. Unlike Treblinka or Sobibor, Buchenwald had not been a death camp—nor, for that matter, a camp for Jews. It was set up in 1937 to incarcerate political enemies of the Reich, including communists, who, by 1943, had succeeded in establishing a well-organized underground, which played a major role in running the camp and prepared for an eventual armed uprising. Over time the camp received many Jehovah’s Witnesses, Sinti and Roma, Soviet POWs, and some Jews, especially after Kristallnacht. Medical experiments were conducted there.

As the Third Reich was collapsing in 1945, the hasty evacuation of camps farther east and murderous “death marches” flooded camps like Buchenwald with thousands of new prisoners, many of whom succumbed to disease and hunger. The number of prisoners increased from 8-10,000 to 48,000 by April 6, 1945. While the SS moved 28,000 prisoners out of Buchenwald as the Americans approached, there were still many prisoners in the camp on April 11, when the first U.S. tanks appeared. That day the communist underground seized control of Buchenwald. Some SS guards and kapos who had stayed behind were lynched by the prisoners. In all, over 56,000 prisoners died in Buchenwald, with more than 1,200 dying after the liberation.

Was Leon Bass a “liberator” or a “witness”? According to the U.S. military, the “liberator” designation applies solely to “those units that arrived within 48 hours of the initial Allied penetration of the camp.” In 1992, Leon was featured in the documentary Liberators: Fighting on Two Fronts in World War II, which became the source of much controversy and rancor when many of its claims were discovered to be inaccurate. But while it is indeed hard to know exactly when the 183rd Combat Engineers arrived, Leon’s presence at Buchenwald is not in dispute. There are pictures of him at the camp. And as Kenneth Stern points out in his report on the Liberators controversy:

It must be recalled that no one—including the inmates—was running a stopwatch and those who challenge whether the 183rd was a “liberating unit” miss the point. The unit was there when it counted, in the first few days, helping helpless souls—true liberators in the second, less technical, but equally humane meaning of the term.

This young man of 20 saw the walking skeletons, the evidence of medical experiments, the crematoria. He saw surviving inmates beat someone to death. But he did not speak of the experience, and he would not talk about it for another 20 years.

Even though Leon encountered hurtful racism when he came home, he returned to a country that was nevertheless slowly changing for the better. President Truman integrated the armed forces. The GI Bill gave veterans, black and white, the chance to get a higher education and buy a home. Leon finished West Chester State Teachers College and found his calling as a teacher, first in an elementary school, then in a high school. Rosa Parks’s refusal to give up her seat on a bus, the Montgomery bus boycott, the stirring leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and his call for nonviolence reassured Leon that the black children he was teaching might yet grow up in a better country than he himself had been born into and had fought for.

In the 1960s Leon faced the greatest challenge of his professional career. He became the principal of a struggling, mostly black inner-city high school in Philadelphia. It was there that Leon had another encounter than would change his life. A Jewish woman survivor, who had been invited to address a class, was telling students about her experiences in Auschwitz, but they ignored her. After all, Leon recalled, these students had their own pain. Leon told the students to listen to the woman. He had been there, he said, and every word she said was true. They looked at the tattoo on her arm. They asked questions. They began to talk to her. They left the room in silence. And as the survivor said goodbye to Leon, she asked him to tell others what he saw.

That day a lot changed for Leon. Hearing that woman talk “pushed a button.” It was time, he realized, to stop suppressing painful memories. “You can’t sanitize history,” either by soft-pedaling the reality of slavery or suppressing the memory of the Holocaust. These were not “black” problems or “white” problems. They were human problems that had to be remembered and that had to be confronted. Until his death in 2015, that is exactly what Dr. Leon Bass set out to do.

———

Additional readings and information

Abzug, Robert. Inside the Vicious Heart: Americans and the Liberation of the Camps. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Bass, Leon. Good Enough: One Man’s Memoir on the Price of the Dream. Lawrenceville, NJ: Open Door Publications, 2011.

Blum, John Morton. V Was for Victory: Politics and American Culture During World War II. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976.

Buchanan, A. Russell. Black Americans in World War II. Santa Barbara, CA: Clio Books, 1977.

Greenberg, Cheryl Lynn. Troubling the Waters: Black Jewish Relations in the American Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Wieviorka, Annette; translated from the French by Jared Stark. The Era of the Witness. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006.

Leon’s unedited testimony at the Fortunoff Video Archive (available at access sites worldwide): https://fortunoff.aviaryplatform.com/r/pk06w96j6r.

###

Leon Bass: My parents insulated us from the kind of pain they had experienced. They never talked about it to us, about the hardships. I guess they figured we would know about it soon enough.

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Those Who Were There: Voices from the Holocaust,” a podcast that draws on recorded interviews from Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. I’m Eleanor Reissa.

Leon Bass was born in Philadelphia on January 23, 1925—the fourth of six children. His parents were born in South Carolina in the 1890s, at the beginning of the Jim Crow era. Just after the First World War they joined the great African American migration north. They settled in Philadelphia with the hope of making a better life for themselves and their children.

As a young man during World War II, Leon volunteered to serve in the United States Army. In April 1945, he and four others from his unit arrived at the Buchenwald concentration camp in Weimar, Germany—just one day after it was liberated.

Forty-three years later, on March 16, 1988, Leon is sitting in a studio in Union, New Jersey. He’s dressed in a plaid brown and beige sport coat, white shirt, and striped tie. He wears aviator glasses and sports a trim, black moustache.

Leon’s interviewers are Bernard Weinstein and Mark Linder. Leon recalls the racial discrimination he experienced as a child in Philadelphia.

———

LB: I went to this school where they always taught us to care and love each other, but to also have love of country. We pledged allegiance to the flag every day, just like every other young person in the city of Philadelphia would do, and we said, “with liberty and justice for all,” just like everyone else, only to go out and find, as we matured, that that was not so, as I found out when I went to the theater. When I bought my ticket, I was directed to the balcony. It was mandated that I go there because I wasn’t good enough to go down on that main floor. And so I began to get a little insight into the society and how the society viewed me, a person of color.

And we always went to the park, and I recall how I looked through that wire fence at this large swimming pool, which I knew I could never use. I would never be admitted, because the society was saying loud and clear to me that I wasn’t good enough. Those are the kind of things that make you feel bad.

I finished school in 1943. I went out and I volunteered. And when I went down to the induction center, institutional racism smacked me right in the face because the sergeant was there, and he told me to go one way when I went through the door, and he told my white friends to go another way. And so I went into an all-black unit, save for the officers. They were white.

Mark Linder: When you enlisted, did you realize the military was segregated?

LB: You know, you hear, but you don’t even think about those things until it hits you in the face. And, of course, the thing that made it more real, more painful, was the fact that they sent us south. They sent us right into the heart of the place where people would—there would be a confrontation. We went to Camp Wheeler, Georgia, for infantry basic training. And we spent quite a time in Mississippi, right in Camp McCain. We spent almost a year there. And we went on maneuvers into Texas, to Louisiana. And we came back to Little Rock, Arkansas.

Now, in all these places, I was given the message of who and what I was as far as the society was concerned. And it was rather frustrating to think that you have made a commitment to your country, and yet your country is saying to you, “All right, you’re okay, but only so far.”

I went into Macon, Georgia, and attempted to get a drink of water while I was in there. A simple thing like a drink of water. Because you walk around the town and you see the fountain, and you go to drink.

I went to drink and someone grabbed me and said, “Boy, you don’t drink here.” And he pointed to the sign which said “white,” and directed me to another sign which said “colored,” where there was another fountain.

Bernard Weinstein: And you were, of course, you were in uniform at the time this happened.

LB: Oh, yes, I was a soldier. Like all the other black soldiers, we were all experiencing this.

ML: Was it your perception, though, that the black troops generally, though, fully understood the fact that, while the rhetoric of the war against Nazi racism and so forth was fine, in practice the country was doing something entirely different.

LB: Yes. It was as though you were schizophrenic. Our country was two personalities. You know, one way we may make the wonderful pronouncements, you know. We talk about our Judeo-Christian ethics, and we want to make the world a better place for democracy and all that other jazz. But then when you get down to the real thing, and you start seeing the way they operate, no, things were not, they were not in consonance. And so I began to be an angry, frustrated, young black soldier.

After my experiences, I really did not want to be in this man’s army. Especially after having to stand on a bus when there were no seats at the back, having to stand up for 100 miles and looking at empty seats. That didn’t endear me to my country. Couldn’t eat in a restaurant. I had to go around the back and knock on the door to get food. And I’m in a uniform. And I saw POWs, prisoners of war, from Germany, being allowed to go in a restaurant to sit down to eat, and yet I was not entitled to that same opportunity.

Our unit left by way of Boston, across the Atlantic and to England, then across the Channel to Le Havre, France. And then we moved up through France and stopped outside of a small town alongside the road and waited for the orders to come down.

And it was into this environment that we began to understand what war was all about. The weather was terrible. It had been raining, sleeting, and cold and foggy. And we had no idea what was going on at that time, because no one had told us that in 1944, around this Christmas season, that the Germans, in a desperate move to try to win the war, had sort of counterattacked and found a soft spot in the lines and then pushed us back and created a bulge.

ML: Which is the Battle of the Bulge.

LB: And so that’s it. We were in the Battle of the Bulge and didn’t know it at the time. And here we are moving up in darkness. It became my first experience with death and dying. You see up to this time, I had never seen anybody even shot or wounded. But here I saw the bodies—on the grave registration trucks, I saw the bodies of people that I knew.

And I remember another time I saw someone I didn’t know. He happened to be white. He’s about my age. And he was on the ground. And his eyes were wide open. They were blue. He had blond hair. And his hands were frozen above his body because the weather was so cold. He had been alongside the road for a while.

And I looked down into those eyes, and I realized that I could end up just like that. And that’s when I began to question my wisdom for having joined the Army. And I wanted to know why I was there. What the heck am I doing here, when I can’t get a drink of water, when I can’t ride on a bus, when I can’t eat in a restaurant? And here I am putting my life on the line, fighting for rights and privileges that I’m denied.

We went to Weimar and set up our bivouac area and then went immediately with an officer, about five of us… We were in the intelligence reconnaissance section of our unit. And we went right to Buchenwald. And that was the day that I was to discover what had really been going on in Europe under the Nazis, because I walk through the gates, and I saw walking dead people. Seriously, walking dead people.

Just looking at these people who were skin and bone and dressed in those pajama-type uniforms, their heads clean shaved, and filled with sores due to malnutrition. And here they were coming towards us, making all kinds of guttural statements, and using their own language.

And it was very difficult for me to comprehend what was going on. I just looked at this in amazement. And I said to myself, you know, My god, who are these people? What have they done? What was their crime? You know, it’s hard for me to try to understand why anybody could have been treated this way, I don’t care what they had done. And I didn’t have any way of thinking or putting a handle on it, no frame of reference. I was only 20.

So this young man who spoke English began to explain to us the composition of this place, that these people were Jews and gypsies. They were trade unionists and communists, homosexuals and Jehovah’s Witnesses. There were some Catholics. There were some, had been some mental defectives, but they were gone.

He went through a litany of groups and names of groups, saying that these people had been incarcerated here, because they—if I could use the term I used before—they weren’t good enough, you see. And they had been put here for one purpose and that was to be worked until they died, or starved until they died.

I walked around the camp. I went to a barracks. I opened a door. I wanted to go in, but the stench came out. And there was no way in the world I was going to get through that overpowering odor. And so I just stood there. And I looked down on the bottom bunk right near the door, and there was a man there. He was skin and bone. He was on a somewhat like a pallet of dirty straw and filthy rags. And he just could barely turn his head and look up at me. And I looked into his face, into that skeletal face with those deep-set eyes, which I can’t forget. But he said nothing. And I said nothing to him.

ML: You were part of an intelligence team in your outfit. There was an officer. Had the officer been briefed? Had the intelligence team been told anything?

LB: I can’t speak for the officers. We didn’t communicate that well. I’ll be very frank with you. So if they knew, I didn’t know.

ML: So it was complete, absolute shock, surprise, when you got there?

LB: Totally. Totally. Had I been told, I doubt if I could have had in my mind’s eye envisioned anything as horrible as what I saw.

BW: Terms like Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen and Majdanek and places like that were not known to you?

LB: I had no idea that those places existed. Later, much later, I began to hear of names and places and realized that there was more than just a Buchenwald, that there were many, many, many Buchenwalds of different names all over Europe and Russia.

That’s what boggles the mind, to think that a group, a society, can organize, and do it in a systematic way, such a program to remove from the world a whole group of people and any others they didn’t think were worthy. And to me, that was just a little bit much. I couldn’t put a handle on that. But I saw what I saw in the camp, the place where they tortured people and the blood stains all around and the instruments of torture there, the building where they had all parts of the human anatomy stored as a result of their experiments, really labeled and put in jars. And I saw the bodies all around. I saw the clothing of little children. But I never saw any children in that camp. But I saw the clothing piled up, neat piles.

BW: Had all the German military left and all the guards left?

LB: Yeah. Those that got away. I think maybe a few might have been captured. I did see one man. He was being beaten by the inmates. They wanted us to come and join them. Of course we didn’t. But it was my understanding that they beat him to death. I’m not sitting in judgment, because I didn’t walk in their shoes. I imagine my voice should have been raised and say, “No, no, that’s not the way,” but I regret to this day that I didn’t.

I went into that crematorium. There were six ovens, six of them. And I looked into one. I saw the remains there, the ashes, the bones. Well, this fellow said that they took the ashes sometimes and used it as human fertilizer. Can you imagine that? To use the ashes of human beings for fertilizer on fields to grow some crops that you would need to promote the war effort.

You know, I saw all of these things, probably more that I can’t remember. But I came out of there sick to the stomach. And I went to the gate to wait. And we all went back to camp on board the trucks in silence. Nobody said anything.

BW: You never talked about it afterwards?

LB: Never. Never. And shortly after that, we were told that our unit was no longer needed, and it was disbanded.

When I came back, I enrolled at West Chester State Teachers College. And my father told me I should be a history teacher. I wanted to be a physical education teacher. He said, “No, I think you should take history. History is important.” And so I became a teacher of history.

I was a happy, young man to think that I could get into college. And I discovered, though, that the same pain that I left when I left here was waiting for me. I was walking down High Street with some of my white friends. And we went to a drugstore, and we went in. And they ordered coffee, and I ordered a glass of milk. There must be about eight cups of coffee, but no milk.

And the lady filled the coffee, put sugar and cream, and kept looking for the manager. And finally, she got his attention and beckoned to him. He came over. She whispered to him. And then he called over one of my white friends and whispered to him. And while doing this looked right at me. And I knew. My antenna was up. I had been conditioned. I knew that something was not kosher. And so I waited until finally the fellow came over, and he looked at the coffee, he said, “Let’s go, fellas, come on.” And he ushered all of us out. And, of course, there was some kind of misunderstanding if a fellow said, “Wait a minute, wait a minute, the coffee is there.” He said, “No, no, we don’t want any.” He said, “Why?” He said, “They didn’t want to serve Leon.”

Can you imagine? I put in three years of my life, put it on the line to make it possible for people like that young lady and that manager or whoever owned that store to function and enjoy the rights and privileges of Americans, and they were saying to me, just like the Nazis did, just like they told me down in the South, what they told my father, “Leon, you’re not good enough.” What a damnable kind of thing to say to somebody.

In 1968, I was asked if I would take over the leadership as principal of a senior high school. It was the Benjamin Franklin High School, and it was for all boys. It was an urban high school, populated with predominantly black and Hispanic youngsters.

And one day, I came to a classroom, and in that classroom, there was a lady. And she was trying to talk to the young men, who were not listening to her. You know, they were doing everything but listening. And I stood at the door, and I began to realize that she was a survivor. And she had survived one of the worst camps. She had survived Auschwitz. And she was here today, on this particular day, to share her experience, her pain, if you will.

And these young men were not listening. They had their own pain, you know. And, and I understood that. You know, the pain of rejection, the pain of not giving—being given the kind of recognition you deserve. I understood all of that. I had been through there, and I knew their pain. But I also knew her pain. And so I had to say to them, “Hold it, fellows, cool it. Listen. What she says is true. I was there.”

And so they got quiet. And once she started telling her account of what happened at Auschwitz, they really listened. And she told them how she lost her grandmother, grandfather, her parents, brothers, sisters, cousins. All those near and dear who had come into that camp, all of them, had gone to the gas chambers and had ended up in the ovens. And of her family, she was the only one that came out of there.

And they listened. And they asked her questions, which made me know that she had reached them. They came up, looked at the numbers tattooed on her arm, and they thanked her. And they did something that hadn’t been done in a long while. They left that room in silence.

And of course, she turned to me. She thanked me for my intervention and, and wanted to know more about my experience at Buchenwald. And I began to remember.

ML: Was this the first time you had talked publicly to anybody?

LB: First time I had told anyone that I had been at Buchenwald. Not my mother, not my, my family, my children. No one knew that I had been there. It was the first time I’d acknowledged that I’d seen it.

After that I—I’ve been talking about it ever since. Anyone that will listen and invites me, I’ll go and talk and tell them, because there are people out there that were saying it didn’t happen. I know it did happen. And so I don’t want them to push it under the rug like they did slavery. I went all through school and knew nothing about that institution and its horrors until I became an adult at the graduate school. Then I found out all the things about slavery that made me most aware of the horrors of that institution that pulled out 40 million souls for free labor all over the world.

We had our four million here in this country. And look what it did to us. Racism has just about split us so many different ways, till we can’t live in harmony with one another. It was an ugly side of our history. And ugly things we want to push under the rug. We don’t want to deal with it. And I’m saying to people today, you must take history with its beauty, and you must take it with its degradation.

BW: In retrospect, Dr. Bass, have you been able to assess why you went through this period of silence where you couldn’t talk about these things?

LB: I guess I go back to Psychology One, where they say things that are ugly and miserable you somehow push it back. And I think the other possibility is that I got busy putting my life together, trying to do those things that I wanted to do, like go to school, get a job, get married. Getting and spending became important. And you don’t deal with things, other things.

And so I go around telling my story. And of course I get the people saying, “Leon, why do you deal with this? This is, this is not a black problem. Why…?” I said, “Hey, it’s not a black problem. It’s not a white problem. It’s a human problem. And we’ve got to face it.”

Really, racism is at the root of all of this. Under that umbrella comes bigotry and prejudice and discrimination. We haven’t come to grips with that institution called racism. And we have to, because we see the ultimate of racism, which was what I saw at Buchenwald.

Do we promote racism through our apathy? When we hear and see things, we say nothing, because we don’t want to jeopardize that which is important to us—our investment in a job, our, our investment among friends. We don’t want to disturb our family, so no matter what people say or do, just leave it alone. Sweep it under the rug, and somehow, it’ll go away.

But the skinheads are with us. The Klan is with us. They may be dressed in Brooks Brothers suits with attachė cases. They may be in… Doctors. They may be lawyers. They may be the guy who drives a bus. But they are still with us.

And I always tell the people when I close my talk to them, I always close it with the words of James Baldwin, who said, “Either we love one another, either we hold to one another, or that sea will engulf us, and the light will go out.”

———

ER: Leon Bass was inspired to tell his own story by the Holocaust survivor who spoke at his school. In the years that followed, he was a guest speaker at synagogues, churches, universities, high schools, and organizations committed to peace and the elimination of racism, sexism, and antisemitism.

Leon Bass died in 2015. He was 90 years old. His wife of 53 years, Mary Sullivan Bass, died in 2002. Leon was survived by a son, a daughter, four grandchildren, and one great-grandchild.

Leon’s daughter, Delia Bass Dandridge, recalls that her father “grew up in a very difficult time in our country, but he had parents who constantly told him he was ‘good enough.’” She says he passed this message on to his children, his grandchildren, his students, and to all those who needed to hear it.

To learn more about Leon Bass’s life story, please visit thosewhowerethere.org. That’s where you’ll find additional background information, photographs, and a link to Leon’s memoir, Good Enough: One Man’s Memoir on the Price of a Dream.

To hear more from “Those Who Were There,” please subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. You can also go to thosewhowerethere.org.

“Those Who Were There” is a production of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, which is housed at Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Department.

This podcast is produced by Nahanni Rous, Eric Marcus, and the archive’s director, Stephen Naron. Thank you to audio engineer Jeff Towne and to Christy Tomecek, Joshua Greene, and Inge De Taeye for their assistance. Thanks, as well, to Sam Kassow for historical oversight and to our social media team, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Ljova Zhurbin composed our theme music.

Special thanks to the Fortunoff family and other donors to the archive for their financial support. I’m Eleanor Reissa. Thank you for listening.

###