By Dr. Samuel Kassow

At the height of the Holocaust, the Germans sometimes spared Jews who had foreign passports. As a result, frantic Jews spent their last savings in order to buy documents that might grant them the right to stay alive. But this was a devil’s game: many documents that seemed safe turned out to be worthless. Hundreds of Polish Jews who bought Uruguayan, Paraguayan, and Guatemalan passports, after spending months in the limbo of internment camps like Bergen-Belsen or Vittel, eventually met their deaths in the Auschwitz gas chambers. On the other hand, documents that at first seemed much less impressive, like Palestine visas, actually helped their owners to survive.

Elias Recanati and his older brother and mother survived the war thanks to their Spanish passports—Elias’s mother was a Spanish citizen before she married her husband, who was Greek. While the Germans sent the Jews of Elias’s hometown of Salonika, Greece, to (mainly) Auschwitz, they allowed Elias’s mother to travel with her two sons to the safety of Spain.

That was by no means a given, however: in most cases, even a Spanish passport was not enough to avoid deportation. As historian Sarah Stein points out, when the deportations from Salonika to Auschwitz began in March 1943, the city had about 860 Jews with foreign citizenship, out of a total Jewish population of approximately 55,000. That number included 511 Jews with Spanish passports, 281 with Italian passports, and six with Portuguese passports. When the Germans asked the Spanish government whether it was prepared to admit “its Jews” into Spain, Madrid failed to send a clear reply. As time ran out, Spain’s ambassador, Sebastián de Romero Radigales, managed to send 150 Spanish nationals to Athens, which was under joint German-Italian administration. Some of the rest reached Bergen-Belsen, but many died in Auschwitz.

It was the Spanish ambassador who asked the German authorities not to deport the Recanatis. Spain’s Salonika consul, Salomon Ezratty, himself a Spanish Jew, watched over the Recanatis at the request of the ambassador to make certain that the Jewish or Greek police, who were collaborating with the Germans, followed the ambassador’s request. (In 2014, Yad Vashem posthumously honored Sebastián de Romero Radigales as a Righteous among the Nations.)

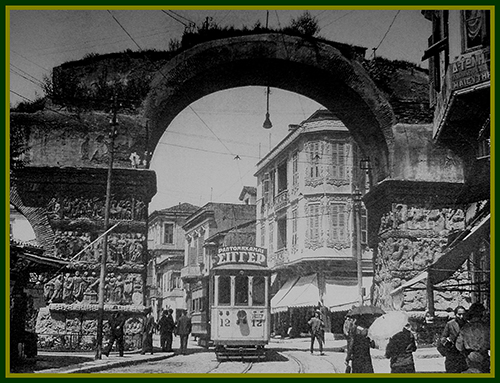

Salonika was a special community, the center of Sephardic, Ladino-speaking Jewish culture in the Balkans. In fact, it was once known as the “Jerusalem of the Balkans.” From the middle of the 16th century until the 1920s, Jews formed a majority of the city’s population. Jews had lived there since Roman days, and the legendary Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela mentioned a community of 500 Jews when he visited Salonika in 1170.

A major turning point in the history of Jewish Salonika came in 1492, with the expulsion of Spanish Jewry. Most Spanish Jews sought refuge in the Ottoman Empire, and Salonika, a port city on the Aegean Sea, seemed especially promising. By the middle of the 17th century, 30,000 Jews lived in Salonika. By 1900 the Jewish population had increased to 80,000. Most of the Jews of Salonika spoke Ladino (Judezmo), the Judaeo-Spanish that their ancestors brought with them from the Iberian peninsula.

During the second half of the 19th century, Jewish merchants and entrepreneurs took advantage of growing rail links to make Salonika a major economic hub that supplied the entire Ottoman Empire with textiles, tobacco products, and hides. The total volume of the port doubled between 1880 and 1912. But rapid economic development also led to wider social differences. Alongside the city’s prosperous merchant class, there were many poor Jews who eked out a meager living as petty craftsmen and dock laborers. The working poor remained a significant segment of the community up until World War II, and many of these Jews became devoted members of Greece’s growing communist party.

During the last quarter of the 19th century, new political trends, such as Zionism and Marxist socialism, gained supporters in Salonika. The Alliance Israélite Universelle established a school that attracted many students and popularized the French language and culture. Ladino newspapers and theaters greatly enhanced the city’s cultural life. Many middle-class and upper-middle-class Jews acquired Spanish, Italian, or Habsburg citizenship. Yet the majority of Salonika Jewry remained religiously observant and traditional in outlook.

Under Ottoman rule, which lasted until Greece took over the city in 1912, the Jewish community enjoyed wide-ranging autonomy and extensive legal protection. With the beginning of Greek rule, the political situation of the Jews became more complicated. Many Greek politicians resented the presence of a Jewish population that spoke a different language and was suspected of insufficient Greek patriotism. The widespread support among Jews for Zionism and communism in the interwar years also aroused suspicion in the minds of many Greek politicians. But slowly many sectors of the Jewish community began to accept a Greek identity. While the Jewish community was still overwhelmingly Ladino-speaking, the younger generation now learned Greek and often attended Greek schools. The new chief rabbi, Zvi Koretz, and many members of the Jewish elite established good relationships with the royal family and leading Greek politicians.

Interwar Salonika Jewry never fully recovered from one of the greatest disasters in the city’s history: the huge fire that broke out in 1917 and that engulfed much of the city, including the main Jewish neighborhoods. The conflagration destroyed synagogues, cultural institutions, and most of the communal archives dating back centuries. The vast majority of the Jewish population became homeless. The rebuilding of the city replaced the old Jewish sections with new neighborhoods that were largely populated by Greek refugees fleeing Turkish rule in Asia Minor.

The aftermath of the fire and the influx of refugees served to make Salonika increasingly Greek. Relations between Jews and Greeks remained strained during the entire interwar period, and in 1931 an anti-Jewish riot broke out. While tensions slowly eased, Greek-Jewish relations were much more fraught in Salonika than in Athens and other cities, and during the Holocaust, Jews in Salonika received much less help and sympathy from their Gentile neighbors.

Salonika’s economy never entirely recovered from the 1917 fire either. Furthermore, the demise of the Ottoman Empire created new national boundaries with Bulgaria and Yugoslavia that isolated Salonika from its traditional commercial hinterland. Jews began leaving Salonika for Latin America, the United States, France, and Palestine. By the beginning of World War II, the Jewish population had declined from 80,000 to approximately 55,000—just under 50 percent of the city’s total population.

In November 1940 the Italians attacked Greece, but they were pushed back by the Greek army. When Germany attacked Greece in April 1941, however, the Greek army quickly collapsed. Many Salonika Jews fought in defense of their country, and over 600 were killed in action.

The Germans seized Salonika on April 9, 1941. Greece was divided into three occupation zones: Salonika was under German occupation; Athens was jointly administered by the Germans and the Italians; and much of Salonika’s immediate hinterland fell under Bulgarian control. During the course of 1941 and 1942, about 3,000 to 7,000 Jews left Salonika for the Italian occupation zone. This group included many of the wealthiest members of the community.

Both Jews and non-Jews suffered terribly from the famine that gripped occupied Greece in 1941 and 1942. Salonika Jewry also witnessed the Nazi looting of the community’s cultural treasures, including old books and manuscripts. The Germans closed the Jewish hospital, arrested many community leaders, and began to confiscate Jewish property. They appointed Sabi Saltiel to head a Jewish council tasked with ensuring that the Jewish population obey all German orders.

On December 10, 1942, the Germans replaced Saltiel with Salonika’s chief rabbi, Zvi Koretz. Koretz was an Ashkenazi rabbi, and even before the war he was disliked by many Jews in the community. Koretz bowed to German demands, handed over lists of the Jewish population, and counseled the Jews to obey German orders. After the war, many survivors accused him of collaboration—a charge that responsible historians consider overdrawn, although they agree that Koretz was weak, gullible, and lacking in leadership qualities.

Salonika’s Jews were trapped. Few Christians were prepared to hide them. Unlike in other cities in Greece, including Athens, the Greek elites and the church leadership in Salonika were indifferent and even hostile. They still regarded the Jews as an alien element. Nor could Jews easily leave the city. Where would they go? In the surrounding mountains, they would simply starve to death.

The first violent persecution of the community occurred on July 11, 1942—known as “Black Sabbath”—when the Germans ordered about 6,500 Jews to gather on Liberty Square to register for forced labor. Compelled to stand all day in the boiling sun, they were harassed, beaten, and humiliated by German soldiers and police. Jews were sent out of town for forced labor; about 700 died.

In January 1943 Adolf Eichmann dispatched his trusted helpers Rolf Günther and Dieter Wisliceny to prepare for the murder of Salonika Jewry. Beginning on February 6, all Jews were required to wear a Yellow Star; on February 25 they were ordered to move into two ghettos. On March 1 they had to submit detailed lists of their property. Rabbi Koretz told the Jews to obey German orders and hope for the best. Helping to herd Jews into the ghettos was a force of 200 Jewish police whose brutality and callousness earned them the hatred of their fellow Jews.

The deportations to Auschwitz (and Treblinka) began on March 15, 1943. By the end of the year, more than 48,500 Jews had been deported to Auschwitz in 19 transports.

This is the historical background for Elias Recanati’s gripping testimony, which relates the last years of Jewish Salonika through the eyes of a young boy. Elias’s memories offer great insight into a unique Jewish world on the eve of its destruction.

———

Additional readings and information

Elias’s unedited testimony at the Fortunoff Video Archive (available at access sites worldwide): https://fortunoff.aviaryplatform.com/collections/5/collection_resources/2094.

###

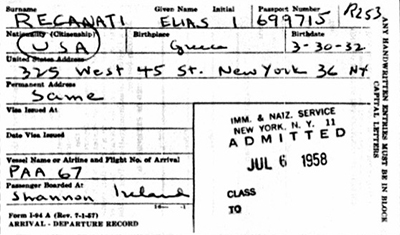

Elias Recanati: I’m Elias Recanati. I was born in Salonika, Greece, on March 30, 1932. My mother’s family was, uh, Spanish. And, uh, it was agreed between the Spaniards and the Germans that, uh, my mother, my brother, and myself would be spared if the Spaniards would give us a visa to go to Spain. Uh, however, in order for us to be able to achieve this, we had to escape from Salonika into Athens.

———

Eleanor Reissa: You’re listening to “Those Who Were There: Voices from the Holocaust,” a podcast that draws on recorded interviews from Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. I’m Eleanor Reissa.

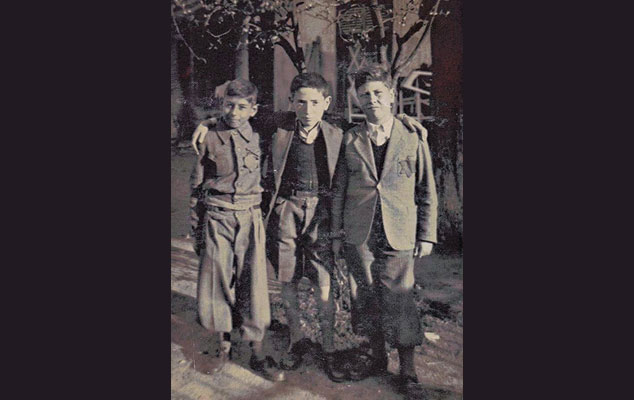

Elias Recanati’s family had lived in Salonika for generations, along with tens of thousands of other Sephardic Jews. His mother was a housewife and his father owned a shop that sold stylish Borsalino hats. It was a shop that his father had inherited from his father. The family lived in a comfortable corner house with a large courtyard where they grew vegetables, and sometimes showed films for the neighborhood children.

Elias grew up speaking Greek and Ladino, or Judaeo-Spanish. Most of the Jews in Salonika traced their ancestry back to Spain before their expulsion in 1492. Four-and-a-half centuries later, German occupying forces in Greece were about to deport Salonika’s Jewish community to extermination camps in Poland.

It is now April 14, 1992, and 60-year-old Elias Recanati is being interviewed by Naomi Rappaport at the offices of the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City. Elias is seated against a black backdrop and is wearing a stylish dark suit, maroon patterned tie, and lightly tinted aviator glasses. He continues with the story of how he and his mother and brother began their perilous journey to safety.

———

Elias Recanati: We were supposed to escape with the help of the guerrilla organization from Salonika to Athens while all these formalities for us to go to Spain were being, uh, processed. In the meanwhile, we had already received the proper papers from the Germans, uh, saying that when our street gets deported, we should be left in our house. And every other day or every few days, uh, you would hear that, uh, last night more people were deported, last night more people were deported. So they were coming closer and closer to our street. So the time came for our street to be deported.

Uh, actually, there were Jewish policemen or collaborators and Greek policemen and the German policemen that were going into house by house, to make sure that everybody got out.

The people that came to pick up, you know, to say get out from the house couldn’t believe their eyes when they saw the orders from the Germans, uh, saying that we were allowed to stay. My father didn’t go. He just hid in the basement. And after everybody left, uh, he disappeared and he went, uh, to my, uh, mother’s cousin.

Now, in the meanwhile, later on, this guerrilla person did come, did pick us up to escape us into Athens. We were with false passports. I was supposed to be a Greek worker that was working in Germany and was coming home for vacation to Athens. And I was supposed to be 18 years old. So…

Naomi Rappaport: And how old were you?

ER: I was 10. So you can imagine, I mean, uh, if I were 16 and there was 18, maybe I would look a young 18, but certainly I could never look 18 at 10. Uh, so it was a very, very scary two days until we arrived in Athens.

NR: How long were you in Athens?

ER: Well, uh, in Athens, uh, only a few months until we completed the formalities to go to Spain. And, uh, actually to go to Spain, we went on a Spanish passport. We left Athens on a military train. We were the only civilians on that train. And by “we” I mean my mother, my brother, myself, and, uh, one of my mother’s brothers was allowed to come and accompany us. Now…

NR: What kind of train, military…? Well, what military, what government…?

ER: This was German military train full of German soldiers that were being moved. Uh, the train was like a regular train with small compartments, and we were given one compartment.

NR: Did they know you were Jewish? Or they knew you were Greek.

ER: They did not know we were Jewish. They knew we were Spanish because we were traveling on a Spanish passport.

NR: Uh, where did the train take you to?

ER: Well, the train took us from Athens, destined to Madrid, making a number of stops in between. Our first stop was Belgrade. Now, when we left, the Spanish ambassador in Athens—this gentleman was a personal friend of my uncle—told my uncle, “Look, I have a letter to send to Madrid. I really should send it to Berlin. But if it goes to Berlin, it will not go any further. I want this letter to go to Madrid, to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, because I’m asking instructions as to what my attitude should be if the Germans start bothering the Spanish Jews in Athens the way they did in Salonika. And the Spanish ambassador in Berlin is very antisemitic, he’s just going to hold the letter, it will not go any further. Would you take this letter for us, for me, to Madrid?” which we did.

And while we were proceeding in the train, knowing the contents of the letter and expecting that there would be a lot of, uh, passport controls and customs controls, somehow my uncle thought that it would be wiser to put that letter away, uh, to hide it somewhere.

So both my uncle and my brother were each carrying sort of a vanity case, and my mother pulled out of my brother’s vanity case the mirror. The mirror was really padded with fabric. So she tore the fabric away it, at the seams, put the letter, and sewed back the fabric so it would not be visible at all.

So we continued, uh, the train ride from Athens to Belgrade. We got off in Belgrade and, uh, we had to spend overnight there in order to continue the journey. So the procedure was that you went to the, uh, German Kommandantur, and they would give you tickets to take a taxi, they would allocate the hotel, they would give you tickets for the hotel, and then again tickets to come back by taxi the next morning to the station, which we did.

And, uh, we waited for another lady to come and meet us there. She was the wife of the first secretary of the Spanish embassy in Athens, and she was also traveling in Madrid. So she came. We met her. We went to the train station. We boarded the train. And our next stop overnight is supposed to be Vienna. So a little before we arrived Vienna, there is again the passport control and the customs control.

And, uh, the fellow that came to inspect our luggage, first thing he did is pick up the vanity case, first thing he did is pick up the mirror from the case, the first thing he did is palpitate with his fingers on the padding of the, uh, vanity mirror.

The case, however, was my uncle’s case, so he couldn’t feel anything. So he continued examining very, very carefully the rest of our luggage. And while he was very, very busy doing that, my brother picked up his case and walked it over to the compartment of the wife of the, uh, secretary, who would not be inspected, traveling on a diplomatic passport.

Now, a German officer—he was a passenger on the train, really—saw my brother do that, and after the inspector finished, he told the inspector what my brother did. So the inspector went to the compartment of that lady. He picked up the case, brought it back into our compartment, and, in fact, found the letter.

Immediately he goes, “Juden.” I don’t know how my mother got the courage to say, “No, no Juden.” So the man says, “Aryan?” So she says, “Yes, Aryan.” Whether this saved us or not, I have no idea. He started inspecting everything again. He picked up every single piece of paper he found in our luggage and he left.

And from that moment on, we were living in fear. You know, what’s going to happen to us? He’s going to read this letter.

So during the course of the day that we spent in Vienna, my uncle went over to the Spanish embassy to relate what have happ—what happened, and to see if we could expect any sort of protection from, uh, the ambassador there. And the answer was totally negative: “You did something you shouldn’t have done. Don’t expect any help from me.”

I remember that my uncle was saying, “We have cyanide in our suitcase. Anything happens, they come to pick us up, uhm, we’re going to take it.”

So the next morning we said we’re going to leave the hotel very, very early, in the hopes that maybe if they come looking for us in the hotel, we won’t be there, we’ll be at the station, which we did. We boarded the train. And, again, the next overnight stop is in Paris.

We felt a little bit better about being on French soil, knowing the language. Once we went back the next morning to the railroad station, we boarded the train for the Spanish border. So we arrived at the frontier and, uh, the Spaniards were amazed to see that we were allowed by the Spaniards to go to Madrid.

Actually, all the Jews that escaped, uh, into Spain by going through the mountains were not allowed to go to Madrid. And, as a matter of fact, the man at the border had to call up the minister in Madrid to inquire, you know, “I have this Jewish family. Well, what’s going on? Is it true that they may proceed to Madrid?” He got assurance that we could. And, uh, well, during the day we were having lunch somewhere at a restaurant and we felt that a lot of people still watching us, and we were wondering, you know, who are these people? I mean, we’re no longer in Germany. What, what’s the matter? Why are they still watching us? How can they harm us here?

It turned that these people were people from the Joint that were there for the special purpose of seeing, you know, which Jews are, uh, going through the border and, uh, do they need any financial help or not. They offered us the help.

NR: How long were you in Madrid?

ER: Uh, in Madrid, again, we stayed only a few months. And, uh, we left for two reasons. As we learned from the Joint, uh, when we went to seek financial help, the Spaniards wanted the Americans to evacuate Spain from all the Jews that were there. Uh, the Americans were saying that, well, “We’re at war, how can we do that? You find the ship and we will pay for it.” And, uh, apparently, there was sort of, sort of stalemate. And then my uncle, who knew the people at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs—one of the top people there was an ex-ambassador to Greece and he knew him—he started again picking up the negotiations. And eventually two ships were found and, uh, one convoy, one group went to Canada, and we elected to go to Palestine because my uncle being in Cairo.

And, uh, when we went to the British consulate in Madrid to apply for the visa to go to Palestine, they were so amazed to look at the passport that we presented to them, uh, that they asked to keep the passport in order to duplicate all these visas for their own spying purposes. They asked for my mother and my uncle to write a long exposé of everything that they saw along the way as to how the tunnels are guarded, how the trains are guarded, which they used for their own intelligence, uh, operations, because I’m sure there was no one else that had traveled in the open throughout the occupied Europe.

NR: How long were you in Palestine?

ER: Well, in Palestine we thought we would be a very short period of time. Uh, just enough time to get the visas.

NR: What year was this?

ER: 1944.

NR: Where in Palestine?

ER: In Tel Aviv. Uh, we took almost one year to obtain the visa to go from Palestine to Cairo, and we did go to Cairo for a few months until June ’45 when the war ended.

NR: And how did you get to, uh, Cairo?

ER: Well, once we had the visa to go to Cairo, we went by train from Tel Aviv to Cairo. We stayed in Cairo at my uncle’s house, again for a few months. Once the war ended in ’45, uh, the Greeks organized a boat, the Greek government organized the boats to repatriate all the Greeks that had escaped. And we went back, uh, to Athens to resume life, uh, to resume life in a way that we did not expect, because then is when we learned that all those people that were in the concentration camps, uh, their fate, what happened. So we’re, we were totally destitute and we lived in my grandmother’s house with my grandmother.

Uh, we were very happy, you know, originally, to, to go back, except for, for what we learned and what we found about the people that didn’t return.

You know, things go through your mind, uh, like a movie sometimes, and sometimes it’s hard to, to tell, you know, what scene is the more dramatic or the most vivid.

NR: Is there anything else that you would like to add to, to this?

ER: I think this portrays pretty accurately, you know, the events of one family. I’m sure there are a million other stories with a million varieties of how the miracle of being saved happened, really, because it’s in a way a miracle.

NR: One last question. I, I know that you have a brother. Do you talk about this at all? Reminisce?

ER: No, not really, no. No, I don’t think I’ve spoken to anybody. Uh, sometimes my mother might mention something. Uh, I, I think it’s a subject that is placed in the background. I think we are at a time which might be that we are all too tired from it.

———

Eleanor Reissa: After Elias, his mother, and brother escaped from Salonika, Elias’s father was deported to a concentration camp in Poland. Elias later learned that his father had been killed.

Before the war, there were 55,000 Jews in Salonika—about two-thirds of the city’s population. After the war, only 2,000 Jews remained in what had been the center of Jewish life in Greece. More than 80 percent of Greece’s centuries-old Jewish population had been murdered—the highest percentage relative to population of any country.

In 1951, Elias, his mother, and brother left Greece for the United States. They settled first in Cleveland, Ohio. Elias started college but dropped out, first working as a shoe salesman, then at a bank. After one bitter Midwestern winter, the family moved to New York City, where Elias attended New York University.

He got his master’s degree in business administration, and worked for the next four decades at the Maritime Overseas Corporation, rising to vice president by the time he retired in 1999.

Elias lives with his second wife on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. He has a son and two grandchildren.

To learn more about Elias Recanati, please visit our companion website at thosewhowerethere.org. It includes episode notes, a full transcript, and archival photographs. That’s where you can also find our previous episodes, as well as background information on the Fortunoff Video Archive and the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

“Those Who Were There” is a production of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, which is housed at the Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Department in New Haven, Connecticut. This second season is a co-production with the Museum of Jewish Heritage—A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, New York’s contribution to the global responsibility to never forget. The museum is committed to the crucial mission of educating diverse visitors about Jewish life before, during, and after the Holocaust.

This podcast is produced by Nahanni Rous; Eric Marcus; the Fortunoff Archive’s director, Stephen Naron; and Treva Walsh, collections project manager at the Museum of Jewish Heritage.

Thank you to audio engineer Jon Gordon. Thanks, as well, to Christy Bailey-Tomecek, Joana Arruda, Noa Gutow-Ellis, and Inge De Taeye for their assistance. And thank you to Sam Kassow for historical oversight, and to photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael Leclerc, and our social media producers, including Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Sara Barber. Ljova Zhurbin composed our theme music. Thank you, as well, to Elias Recanati for providing archival photographs and background information.

Special thanks to the Fortunoff family and other donors to the archive for their financial support.

I’m Eleanor Reissa. Thank you for listening.

###